Dompiere and Mont St. Quentin

AUGUST 1918

Sunday, 25th. Letter from Dorrie today. She was wondering, a little anxiously, it seemed, if perhaps I were in the "big push" that has been going on of late.

This afternoon, without any previous warning, orders were suddenly issued for the battalion to pack up and be in readiness to move up to the front tonight. We packed our valises hurriedly, ready to be taken to Corbie to be stored. A reshuffling of officers took place, and I was put in "C" coy., in charge of No.11 platoon, there being now only three platoons to each company.

Wrote a letter to Dorothy, and enclosed the remaining £2, but don't know when I'll be able to get it posted.

This evening we were to give a return dinner to the officers of the 23rd. Bn., and although the "moving orders" rather spoilt things, we carried on with it. Of course they didn't all turn up, and a lot of the stuff provided was not used. The services of "The Bandicoots" concert party had been enlisted to favour the occasion with a performance. But the concert had just got well under way when it was announced from the stage that the order had come for the battalion to fall in.

So the entertainment broke up, and we fell in, but were kept waiting about for a couple of hours or so. At dusk we marched out along the Corbie road a short distance, where motor transport cars were waiting to take us up to the line. The accommodation was extremely limited, with the result that the poor "diggers" were packed like sheep in a pen. The rain, which had been threatening for some time, began to descend heavily just as we got settled in the cars.

Passing through Aubigny and Fouilloy, the column lumbered slowly up the Villers-Bretonneux road. It was a very dark night, and no lights were allowed on the vehicles, which made the driver's job rather difficult. He had to keep in touch with the rest of the column, as he had not been informed as to his destination, a most stupid manner of proceeding.

Sure enough, the foremost part of the column got right away from us before we reached Villers-Bretonneux, but a traffic policeman in the village assured us that they had taken the road to the left, which leads to Proyart. The rain came down in torrents, and we were all very thankful to be within the shelter of the cars. Moving on eastward through Warfusée along the scarcely discernible main road, we passed one of the cars, which had run into the ditch by the roadside. A little later we caught up with the rest of the column.

The cars came to a halt somewhere in the vicinity of Proyart, and we all disembussed and waited, just off the road, for orders. We were very fortunate, for the rain had ceased, and we were able to get a little rest lying on our ground-sheets on a grassy bank. Somebody discovered that some troops camped near by had some stew and tea to spare, so I got my platoon a good feed out of it, besides most of the rest of the company as well.

Monday, 26th. Falling in again, we marched off along that road a little way, and then turned off along a track going down to the left. A few odd "heavies" were landing at scattered intervals about the landscape. One of these unwelcome visitors, a 5.9 I think, exploded a couple of hundred yards away, and pieces of the shell-casing whizzed savagely past us. With the instantaneous fuses now used in the German shells, a surface burst is obtained, and that gives the shell a much greater effective area than when they used to explode a couple of feet below the surface of the ground, the pieces then flying up at a comparatively high angle.

Arriving at some trenches on the top of a low ridge, we settled down there for the rest of the night. Sedgwick and Graham, the other officers with "C" coy., rolled up together in a blanket, and I crawled in under the cooker, wrapped in overcoat and groundsheet, in case there should be any more rain. Managed to get a few hours' sleep before dawn, but it was rather cold.

After having breakfasted, I took a walk down to Méricourt, which was a few hundred yards away, on the Somme. It was just the usual deserted shell-battered village. On many of the buildings were billeting signs in German, such as "Keller. 14 man". Looked through the church, which had evidently been used either as a billet for soldiers or as a dressing-station.

Tractors and agricultural implements which were used by one of the British auxiliary petrol companys to plough the country around Mericourt as part of post war educational and vocational training. Some members of the AIF were sent for instruction in this non military employment.

Tractors and agricultural implements which were used by one of the British auxiliary petrol companys to plough the country around Mericourt as part of post war educational and vocational training. Some members of the AIF were sent for instruction in this non military employment.

A church is at the end of the street in the background.

This afternoon the colonel called the officers together and told us that we were to attack in the morning, the first objective being the village of Dompiere. We can reckon on getting very little artillery support. The line we are going to is very indefinite, on account of enemy withdrawals, and that will make our task of attacking rather more difficult.

Some officers and N.C.O's were required to go forward on a reconnaissance for each company. Sedgwick and I, with a serjeant, went from "C" coy. Crossing the ridge and a large valley, we got up to the Chuignolles road. We encountered many signs of the recent German occupation and their hurried retreat. Lots of burnt-out ammunition dumps were dotted here and there, and vacated gun positions. German notice boards and warnings were posted at many points along the road such as, "Schritt! Eisenbahn", "Achtung, Eisenbahn", "Gasalarm", "Eintrit verboten", and many others.

In the village of Chuignolles a number of brick and wood huts had been built by the Huns during their occupation, and some of these still remained intact.

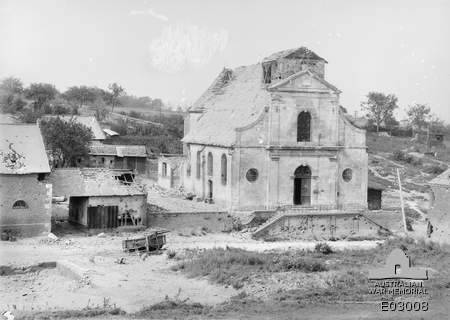

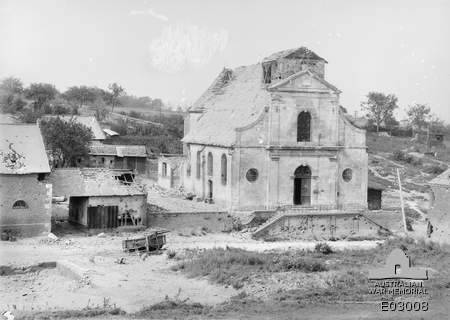

The Church of Chuignolles, the day the village was taken from the

The Church of Chuignolles, the day the village was taken from the

Germans by the Australian troops. Note the shell damaged buildings.

Arriving at Bn. Hqrs. we waited there for some time. Then Colonel James came along and told us that the attack has been indefinitely postponed. We are to take over a portion of the line in front of Dompiere, C coy. to be in support. Patrols will be sent out to reconnoitre and get in touch with the enemy, who, it is suspected, is beginning to retreat on this front.

Sedgwick went forward with Major Ellwood to reconnoitre the positions allotted to us, but the colonel sent me back to the company to help bring them up.

While going back through the village, I stopped to have a look through an old German billet. Picked out a few papers and documents from among the disordered litter lying about. Found a small glass bulb half full of a brown liquid and containing a detonator connected to a fuse with match-head composition on the end. Out of the town a bit I placed the glass bulb on a big lump of paper in the bottom of a trench, and set alight to the paper, so that it would burn up and ignite the fuse. Nicked around into the next bay to await events. Presently there was a scarcely audible report, and I came back to investigate. Sniffing in the trench, I detected a slight smell of gas, and then, bending lower, I caught a good hefty sniff of the vile stuff, which immediately set my eyes weeping and caused a short burning pain in my nose. It was a little-used kind of gas, which we had dealt with at the Corps Gas School, and of which I forget the name.

Wandered back to the coy. in time for tea. Wound strips of bagging over my light-coloured puttees to camouflage them, as they are too easily noticeable for going into a stunt with. Then the coy. moved forward in an elastic string of platoons in single file, passing to the left of Chuignolles, to the assembly point on a steep hillside just beyond a deep valley which contained a vast timber dump, which the Huns in their hurried flight hadn't time to destroy.

At the assembly point we were kept waiting about for several hours, until darkness began to set in. Then we got a move on and went forward across a wide valley and up a long low hill to the Support position, which was in a communication trench. The accommodation was very poor, and most of the men had to set to work and dig holes for themselves in the side of the trench. I got a bit of a wooden shelter from the wind and the weather, which I shared with my batman and another man. Sedgwick and Bill Graham established themselves in a deep German dugout, making Coy. Hqrs. there.

Graham had to take out a patrol of thirty men to reconnoitre the ground in front, and especially the ruins of an old sugar factory in front of our lines. He went out just before midnight. Turned in under my wooden roof for a few winks of sleep.

Tuesday, 27th. The Hun sent over a goodly portion of "iron rations" during the night. Some fell fairly close to our trench, but they seemed mostly to go right over into the valley behind. A few whiffs of sneezing gas drifted up our way, but I managed to get a fair amount of sleep. Graham's party returned towards morning, having met with some resistance at the sugar mill.

After having breakfasted, about half-past nine, Sedgwick suggested that I go forward and get familiar with our front. Went forward, accordingly, and found Captain Ball established in a copse a few hundred yards this side of the sugar factory. The front seemed to be very indefinite indeed, and consisted merely of a chain of posts ----- with mighty big intervals between the links! Tonto said he had sent a bombing party along a trench that meandered off to the left, so I set out to follow and find out what was doing. The trench was a very old one, thickly overgrown with tall rank weeds, but there were many indications of its recent occupation by the enemy; pieces of equipment, "potato-masher" bombs, an odd mauser rifle, and packets of German flare cartridges; also large glass bottles encased in cane wicker protectors. On first seeing these bottles I thought they were probably used for the rum issue.

After going several hundred yards and seeing no sign of the bombing party, I decided that it was just as well to proceed cautiously, not knowing what moment I might possibly walk into a German post. Picked up a couple of Hun bombs to make use of in such an emergency. On getting close to the road which runs from Cappy to near the old sugar factory, I considered it unwise to go any farther alone, so turned back.

Then it was that I caught sight of the familiar round-topped helmets in a trench some distance forward, so I got across there and found a post manned by 22nd.Bn. men. One of them thought he detected some movement in a large copse to the left rear of the old factory, and several of them had seen some Huns moving about some distance over to the left. Got to work with my field glasses to see if I could pick up anything, and after a time I made out what appeared to be an enemy post with a sentry on duty. I got some 22nd.Bn. Lewis gunners to bring their weapon into a suitable position from which to give the enemy post a few bars of the "Hymn of Hate", but just then one of their officers came along, and he reckoned that it would be better to put a few Stokes mortar bombs over, a rather stupid idea, I thought, considering the target was so small. He also decided to send out a patrol to take the post.

Went along with a few of the men to where the trench met the road and ended abruptly. Observing from there with the glasses, I could plainly distinguish two Huns, one standing in a trench thickly overgrown with vegetation, with only his head showing. Evidently he was on sentry duty. The other one was moving about among some small scrub out of the trench.

The first Stokes bomb went over and did not get within bushman's coo-ee of the post. Of course the Huns slipped into obscurity like a startled snail into its shell, save that the sentry still remained on duty. A few more bombs went over, and managed to get a little closer, and the sentry also faded out of the picture.

Meanwhile the patrol had congregated in the end of the trench, ready to skip across the road to a trench on the other side. I spotted some more Germans farther back, about 800 yards away, and got a serjeant to snipe while I observed. They were not visible with the naked eye, so the serjeant could only aim at the point where they were. However, it made them shift out of the way. By this time our position had attracted some attention in the form of rifle fire and angry little bursts from a machine gun. A sniper had evidently got his eye on me, for a couple of bullets scored miniature furrows in the earth within a few feet of where I lay observing.

About six or eight Stokes bombs altogether were consigned to Fritz, and one of them actually managed to fall within about ten yards of the spot where Fritz had been.

The patrol party began to cross the road, one at a time, and the enemy fired a good lot of bullets at them while crossing, but failed to hit anybody. I had determined to take part in the fun, so when the party had all got across, I waited a few minutes and then hopped out and dashed quickly across the road, while a few bullets bit holes in the air close around me. Jumped into a deep trench and stopped for breath. None of the patrol were in sight, and there were two trenches, one going straight towards the enemy post, and the other leading away to the left. Went up to the left for some little distance, but could see no sign of them, so returned to the starting place. A corporal had come over to be in the scrap, although he did not belong to the patrol, so he and I crept cautiously forward along the other trench, keeping a sharp lookout lest we might run into a trap.

Having approached quite close to the tall trees near which I had located the German position, and seeing no sign of the patrol, we decided that it was unwise to go any farther in that direction. A few bursts of machine gun bullets tore up the loose earth of an old trench parapet some distance over to our left, so it appeared evident that the patrol must be somewhere in that vicinity. Accordingly, we went back and took the trench to the left, and eventually found the party sitting down in the trench about quarter of a mile away.

They were taking things easy and seemed in no particular hurry to come into contact with Fritz, and it was now past dinner time, so decided that I might as well go back to the company as wait there all day perhaps for nothing. Accordingly, I departed and followed a trench which took me back to the road opposite where I had first come to it before meeting the 22nd. Bn. men. Among other litter left by the Germans, there were here a couple of the aforementioned "rum" bottles, and investigation showed one of them to contain a fair amount of liquid. Having developed a considerable thirst during the morning, I at once decided to quaff some of the doubtful liquid, whatever it might be. Happily, it proved to be only tea, of a rather rank and tasteless quality, but nevertheless very acceptable.

About that time the Germans began to send over a liberal issue of Hate from their field artillery, also a few heavies, to the Support and Reserve lines. The sugar factory also fell in for a fair amount of strafing. This lasted for about half an hour or so, and very obligingly ceased before I got back near our lines.

Arriving at the copse where were "D" coy's hqrs. I learned that Baldock of "B" coy., who had occupied the sugar factory with a couple of platoons, was shelled out of the old ruins and sustained a number of casualties.

I found that "C" coy. had moved forward, during my absence, from the communication trench into a line trench a few hundred yards behind the copse. Discovered Coy. Hqrs. in a good roomy shelter from the weather, and got busy with a belated dinner.

This morning's ramble is a bit of a landmark in my military career, because, for the first time since leaving Australia over three years ago, I actually saw the enemy in his own territory. Previously I had only seen prisoners and killed, though on one occasion at Hill 60 I saw, through a telescope, the reflection of a Hun sentry in his own periscope.

Slept a little during the afternoon. Rain set in, making things miserable generally, and the Hun carried on a lot of spasmodic shelling, mostly on the Reserve areas. A few landed in the vicinity of our trench, but none very close. Some of them, however, contained sneezing gas, and the noxious fumes wandered over our way, and caused us a lot of inconvenience and discomfort. The bombardment, which was rather severe on the ridge behind, quietened down towards evening.

A runner happened to be going back to Bn. Hqrs., so I got him to take the letter I had written to Dorrie on Sunday, to have it posted for me.

The ration party was considerably delayed, our supply of water was exhausted, and all of us were feeling rather thirsty. My thoughts wandered frequently over to that bottle of German tea. Darkness was setting in, the night was damp and dreary, and the now sodden ground was both sticky and slippery where it wasn't overgrown with grass. And the tea was a good eight hundred yards away, but still it was very desirable. So eventually, after having been along the line to see that things were all in order, I struck out for the copse in front. It was so very slippery in the trench that I reckoned it best to get out on top, but the going there was just as bad on account of the short thick scrub and the branch trenches that had to be crossed. (They were too wide to jump over.) It was now quite dark, and, as though to add to all those discouragements, a light drizzling rain set in, or rather, revived. Several times I thought seriously of going back, but having once set out, I kept on out of sheer obstinacy. Nevertheless, I made a mental vow that I'd see German tea in Hades before I'd go out after it again on such a night.

Arrived at the copse and picked a cautious way along to the left, keeping close to the trench, but it was so dark that there was grave risk of getting away from the trench and becoming lost in that wilderness. And, with the multitude of trenches running in all directions, once lost there would be no finding the way again. So I got into the trench. The thick tangle of long weeds growing up the trench sides hampered progress somewhat, and the clay bottom of the trench was so slippery that I fell a number of times. Was not too sure that I had kept to the right trench, until coming to a block in the form of a mass of barbed wire, which I remembered having encountered during the day.

Thenceforth the way became more grassy than ever, and it was with great difficulty that I managed to keep on my feet. At last, with no small degree of satisfaction, I came to the road, and soon found the bottle of tea. It was immensely welcome, for my thirst was great. Drank as much as I wanted, filled my water-bottle with the stale stuff, and then set off back again. Arriving at the copse, I abandoned the trench and struck off across the open. Very nearly got lost, only a tall tree which showed dimly through the darkness served as a guide by which to find our Support trench.

Arrived at Coy. Hqrs. at last, my outer clothing wet through with rain and my inner clothing soaked with perspiration, and all for the sake of some stale German tea. However, the bottle-full I brought back was greatly appreciated by the others in the dugout.

Some time later the belated rations arrived, and we dined. The party had been held up by shellfire, and were not able to get near the ration dump for a long time. One of the tea cans had the nose-cap of a yellow cross (mustard gas) shell in it. The man carrying it had spilt a lot of the tea all down one side of his clothes, with the result that the gassed tea dyed one side of him a bright yellow.

Lay down on my bunk, but was so uncomfortable in my wet clothes that sleep was out of the question. A messenger came through from Hqrs. stating that the French have captured Roye.

Orders came through for Bill Graham to take out a reconnoitring patrol and ascertain whether or not Fritz had absconded. He took fifteen men and a Lewis gun.

Wednesday, 28th. Went out on a tour of the lines to see that all was in order, and found things extremely lax. Scarcely a gas guard or Lewis gun were to be found mounted. The N.C.O's. had neglected their duty shockingly. I stirred things up a bit, and got the Lewis gun mounted and the gas guards on their job, and roused a treat over the criminal carelessness shown by some of them.

One of our signallers, listening in on the phone while two of the companies were speaking, overheard "D" coy. say that four of Graham's patrol had arrived there, very scared and excited, with the news that the patrol had met "thousands of Huns!" and they didn't know what had happened to the rest of the party. The rest of the party returned about half an hour later, and it transpired that the "thousands of Huns" were "B" coy's. patrol, a lively little scrap having taken place between the two parties until one man jumped up and yelled, "Put it into the-----!" whereupon some of the opposing side called out, "Who the ---- hell are you!" and hostilities promptly ceased. Fortunately only one man was wounded. It also turned out that the Germans had vanished from the locality earlier in the night.

Turned into my bunk and got a couple of hours' sleep before daylight.

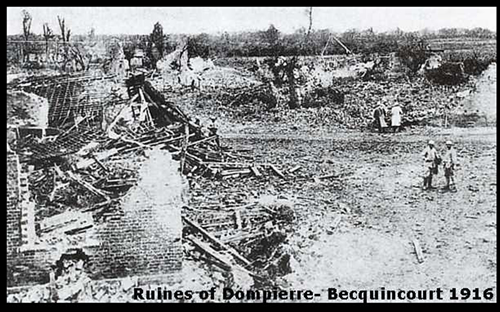

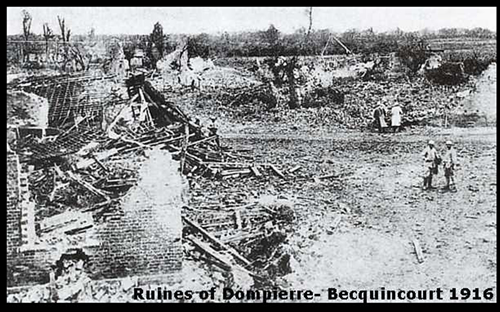

Orders came over the telephone for "C" coy. to advance on Dompiere, mop up enemy posts, if any, in the village, and establish a line on the far side. It was about six o'clock, and broad daylight, before the company was ready to move forward. We advanced in artillery formation past the copse, and assembled in front of the large copse on the left of the sugar mill. Sedgwick explained his tactics to us, and we again went forward in artillery formation, but he didn't seem to know his own mind, and changed his plan of action a number of times, thus causing a lot of confusion and delay. Consequently the companies on our flanks had reached their objectives while we were still on the way. Eventually we advanced in a line of sections in single file. The ground here was pitted with old craters and shell-holes, this having been the line from which the Somme offensive was launched in July of 1916, with Dompiere as one of its first objectives. Dilapidated entanglements of rusty barbed wire twisted about in chaotic confusion. The road (from sugar mill to the village) had been blown up by a mine in one place, but this appeared to be of more recent occurrence. Farther on, a great gaping mine crater, now overgrown with vegetation, appeared in the field, and the ruins of old-time trenches were in evidence on all sides. We were advancing over a famous battlefield of over two years ago. Bombardments of bygone days had reduced the township to a mere collection of broken walls, around which the thick vegetation grew in profusion.

Encountering no resistance, we went straight on through the village to our objective on the far side. Some 22nd. Bn. men had gone somewhat farther forward, and were met by machine gun fire from Herbécourt, the next town in front.

The line we occupied ran through the ruins of Becquincourt, a small village adjoining Dompierre. In it were many cellars strengthened and fortified by the Huns for use as dugouts. We selected one of these for Coy. Hqrs., and, as a little rain began to set in, we were very glad of the shelter. Some German equipment lay scattered about the floor, and I appropriated a Hun bayonet, a fine-looking weapon, for a souvenir.

The enemy began a spasmodic bombardment of the village and vicinity, mostly with heavies. Sedgwick had put the company into an open trench, where they were exposed both to the weather and to enemy shellfire. Thinking it was a pity that such a lot of good cellars should go unused, I got the greater part of my platoon installed in several of them, for which they appeared very thankful.

The enemy now honoured us with intermittent savage gusts of shellfire, more particularly on our left, where the 22nd. Bn. were quartered in a trench, but these quietened down towards midday. Returned to the Hqrs. cellar, which was supplied with a number of bunks, and, my eyes being heavy with drowsiness, lay down on a bank and slept soundly for about an hour.

While we were lunching, Captain Ball came along and told us that "C" coy. was to be in Support, and therefore we would have to find a position somewhere in rear of the other three companies. The task of finding a suitable position fell to me.

Took a corporal and a runner with me and went out to explore the ground in rear of the battalion, taking care to keep well clear of Dompiere, where every few minutes a heavy, probably 9-inch calibre, would crack with an awful explosion, sending up great clouds of smoke and red brick-dust.

Managed to find some fairly good trenches, with a number of dugouts, about eight hundred yards back. Met a Tommy artillery officer who wanted to know just where our front line was situated, so that he could fire his battery without fear of killing our own men. Not being able to give him the definite location of our front line, I advised him to fire into Herbécourt, as there were none of our troops there. A little later we heard a few shells swishing by overhead on their way to Fritz.

Went back to report the result of my quest to Coy. Hqrs., but, on arriving there, found the scheme of things somewhat disarranged. Orders had come through that the double line of trenches running from Herbécourt to Assevillers were to be occupied by this battalion before nightfall. Possibly they had been evacuated by the enemy, but it was known that they were lightly held this morning with machine gun posts. Reconnoitring patrols were to be sent out at once by the companies to make sure of the ground to be occupied. If the enemy should prove to be there in force, artillery support would be called for before the companies moved forward. But if only scattered posts were encountered, they were to be "mopped up" by the patrols, if possible, thus enabling the companies to move forward unmolested.

It fell to my lot to take the patrol for "C" coy., which was only fair, considering that Bill Graham had been out on patrol two nights in succession. My party consisted of fifteen men, including Sjt. Webb and several other N.C.O's. Baldie, another "2nd.-loot", had to take the "D" coy. party , and our instructions were that both parties proceed together from Bn. Hqrs., shown thus P on the map, along the communication trench which runs forward between Becquincourt and the mill, towards our objective, the two trenches named Brunhilde and Attila, respectively. A Lewis gun accompanied each party. On reaching Brunhilde trench we were to separate, Baldie going to the left and I to the right, and both eventually coming together again along Attila trench, and returning by Guadeloupe Alley to Becquincourt.

It looked very simple on the map. Captain Ball gave us explicit directions. We were going out essentially for information, and must not buy into a fight unnecessarily. Two signallers with telephones would accompany us along the communication trench, and we were to make periodical reports of our progress. Tonto seemed a little bit anxious about us.

We started off about quarter past three, and were to be back not later than half-past four. Took my patrol in the lead, and kept well near the front, with only a couple of good bombers ahead of me. The communication trench was blocked in some places with dugouts which had been built across the trench. We proceeded with a good deal of caution, and I checked our progress carefully by the map, also making observations with my field glasses, in search of any traces of the enemy. Suspicious and alert, we moved on past some abandoned huts on our left. When we arrived opposite the Mill, about which was situated a number of huts and aeroplane hangars, I was scanning the place carefully through the glasses when I suddenly detected some movement, and the next moment a couple of the familiar round-topped helmets came into view. I learned afterwards that they were Sjts. Jim Collery and Jack Cumming. They walked freely among the huts, so it was evident there were none of the enemy there. The Huns had shown some taste for decorative art in the camouflaging of these huts, for the camouflage consisted chiefly of drawings of various objects, such as aeroplanes, German soldiers, etc., all over the walls.

We moved on past the junction of Reunion Alley, and then the signallers' supply of telephone wire came to an end. Told them to ring up Hqrs. and ask for a further supply to be sent out at once, but, on connecting up, they were unable to get the telephone to work. Therefore nothing remained but to send one of them back as a runner to report our progress so far, and to ask Hqrs. to keep in touch with us by means of runners.

Bursts of machine gun fire some distance away on our right caught my attention, and it soon became evident that one of the other company's patrols had met some resistance from the direction of Assevillers. We could see the tiny clouds of dust raised by the bullets striking some soft earth a few hundred yards in front of the village. That, however, did not concern us, and we pushed ahead.

According to all my calculations and checking progress by the map, the next branch trench should have been Martinique Alley, but on arriving there I found that, besides the expected trench branching off at an angle to the right, there was another branch running off to the left, this latter being, apparently, another old-time trench like the others. I naturally concluded that the trench on the left had somehow been omitted in the making of the map, but was a bit doubtful, so conferred with Mr. Baldie, who expressed the opinion that we were already at Brunehilde trench. This suggestion was supported by the fact that several trees could be seen a few hundred yards ahead, these, he considered, being what was left of the trees shown on the map along the road a few hundred yards farther on than Attila trench.

Brunehilde & Attila trenchs 1918 – This was taken from a large map purchased from AWM

Brunehilde & Attila trenchs 1918 – This was taken from a large map purchased from AWMUnconvinced by his argument, I took the serjeant and several men of my patrol and went ahead to investigate, knowing that if we were at Brunehilde, we ought to find Attila about two hundred yards farther forward.

However, we approached quite close to the trees without finding any sign of another trench, and I was getting rather bewildered, and thought lots of nasty things about those responsible for making the map. A fallen tree-trunk lay across the trench, and beyond that there was a disused dugout built in the trench and partly blocking it up. Going ahead alone, I crawled under the tree and over the dugout, and was approaching a bit of a shed built in the trench under one of the trees, when suddenly I was greatly startled to see some movement inside the shed. It was only a horse, tied to a beam, but it gave me an unpleasant shock for the moment. "There is no smoke without fire", and there is no tethered horse without someone to have tethered it. Being alone and an advocate of discretion as the better part of valour, I did not waste many seconds putting a good twenty or thirty yards between me and the shed. Then, taking the serjeant and a couple of men with me, we crept forward very cautiously, not knowing what moment a shot might ring out and one of us fall dead.

Closer inspection showed the horse to be a lean decrepit old moke, little more than a skeleton. He had evidently been tied there many days, and looked as if he had had nothing to eat for over a week. The beam he was tied to, a great wooden girder about 8 inches thick by 12 inches broad, was eaten half through by the unfortunate starved brute. Every vestige of bark was picked clean off every piece of wood within his reach. This is just another example of the wanton and unnecessary cruelty of our barbarous friend, the enemy.

Gingerly we crept forward past the old horse, keeping a very sharp lookout for the wily Hun. Found the trench beyond the shed blocked up with dugouts and disused stables. Scanning the surrounding landscape through my glasses, I spotted, about six hundred yards away towards Herbécourt, a solitary Hun standing behind a bush and looking steadfastly in the direction of Dompierre. Possibly he had a telephone and was observing for the artillery. Anyway, we were unable to disturb his tranquillity with a bullet, as that would have betrayed us to the enemy who might be lurking near and with whom we might yet have to deal before completing our reconnaissance.

After having a good look around and seeing nothing else worth noting, we made our way back to the others. Baldie still maintained that we were at Brunehilde trench. I thought he seemed just a little too eager to take that for granted, and wondered if he were afraid of going farther forward. However, there was nothing else for it but to accept his suggestion, so I took my party out along the trench leading off to the right, leaving Baldie to go with his men to the left.

Had not gone a great distance when I found an old noticeboard, marked "Martinique Boyau", lying in the trench. So, after all, my first conclusion proved to be correct, and this was Martinique Alley, and the trench going to the left was one not marked on the map. Baldie's reconnaissance would be valueless, as it would not affect the prescribed trenches, unless he discovered his mistake. However, there was no time now to make any fresh arrangements, so I decided to go right along Martinique, and get to Attila trench that way.

Martinique Alley, like most of the trenches hereabouts, was one of the old-timers, probably dug by French troops in 1916, and was now mostly overgrown with weeds and long rank grass, though in many places the vegetation had been worn away by recent occupation by the enemy. Evidences of their presence were to be found everywhere, and one of the men ventured to suggest that the marks of their boots in one place, where they had been climbing out of the trench, looked very fresh and recent. I reminded him that the Huns had been in occupation of all this territory, as far back as the sugar factory, less than twenty hours ago.

We arrived at the Brunehilde crossing, lingered a minute or two to make sure there were no Huns about, and pushed on again. It was getting late, already well after four, and we had yet a good long way to go. We must get a hustle on, I decided. Speed was necessary, but could only be gained at the expense of caution, and that seemed hardly fair to the two bombers leading the way. So I took the lead, pistol in hand, and set the pace, maintaining extra vigilance to avoid being surprised. Silently and swiftly we stepped out along Martinique and soon arrived at the Attila crossing.

No Huns were to be seen about, so with increased assurance we meandered steadily through the bays and traverses of Attila trench going up to the left towards Guadeloupe Alley.

The trees where the horse was loomed into view about quarter of a mile back towards Dompierre. Before long we appeared to be almost right behind the trees, and I was expecting to see Guadeloupe Alley at any turn.

Then the unexpected happened. Turning the corner of a traverse, I spotted, at the far end of the bay, less than ten yards distant, a Hun sitting in the trench with his head bowed forward as though asleep. I backed around the corner "toute de suite", and the others must have thought I had seen the whole German army advancing, for they turned to beat a hasty retreat, but I beckoned them forward again. Hurriedly explained the situation and the plan of attack --- a few bombs into the trench ahead and then rush in quick and lively.

The serjeant and I and several of the leading men got a bomb each ready. For the life of me I could not drag the pin out of mine, and the corporal just behind me was evidently in the same difficulty. The serjeant flung his grenade and several more followed from the men. Discarded mine in disgust. "Righto, lads!" I yelled, "hop into them!" but the men hesitated. It was a matter of life and death, when moments count. "Come on, boys!" I shouted, and dashed forward into the bay, revolver in hand, the sergeant following close behind. Two panic-stricken Germans were in the bay. Others were making themselves scarce along the trench. There was an earth block across the trench between the bay we were in and the machine gun position beyond. One of the Huns cowered in a corner, but the other attempted to get away over the block, and the serjeant and I fired simultaneously --- my first shot actually fired at the enemy. He appeared to have been hit, but not badly, and, prostrate on the parados, tried to hold up his hands, the look on his face a piteous plea for mercy.

The muzzle of a rifle appeared over my shoulder. "Don't shoot!" I cried, "he's done!" Too late. The man fired, and the Hun sank limply on the ground, mortally wounded.

A wave of regret for the needless murder swept through my heart. I stood over the other poor wretch to prevent him being similarly dealt with. "You're mine!" I exclaimed, but he only grovelled at my feet, begging piteously for mercy. I motioned to him to stand up. He obeyed instantly and put up his hands, but still cowered from me with fear of being shot. I signed to him to go back along the trench, where the diggers would take good care of him. He went hurriedly, with a furtive glance backward, as though doubting my intention to let him live. All this happened in about six seconds from the time we rushed in.

Our next job was to secure the German machine gun, which lay mounted on the parapet in the next bay, pointing towards Dompierre. Some of the men, with rifle and Lewis gun, were exchanging shots with the Hocks who had escaped. I ordered the men to get the Hun gun, but again nobody seemed willing to go forward. I decided to go over first to encourage them, and sprang up on to the earth block. As I did so, a man called out, "Don't go over! There's a bomb not gone off!" The words were immediately followed by an explosion three yards in front of me! It was one of our Mills grenades with those treacherous 7-second fuses. A merciful Providence preserved me when my chances were small, and, remarkable as it is, I was not even hit.

Next moment I was down in the gun position. At the same time a head protruded from a small hole in the trench side, and two trembling hands were raised. Another Hun appeared behind the first. They had evidently huddled in the funk-hole to wait till the bomb exploded. Demoralized with fear, they gasped, "Pardon, m'sieur! Pardon, m'sieur!" meanwhile shrinking and writhing on the ground, like a threatened cur at the sight of an upraised lash. The excitement must have made me look fierce, for they seemed to think their last moments had come. Murder, however, was the farthest thought from my mind. In spite of the seriousness of the occasion, I could not help being rather amused, and not a little surprised, at anyone being terrified of me!

I hustled them back into the other bay, and again called for someone to collar the gun. The corporal scrambled over the block, grabbed the weapon, and struggled back again with it over his shoulder. We were all eager to get away lively, in case the escaped Huns should gather reinforcements and make things uncomfortable. We could see no sign of Guadeloupe Alley. (Had I known it, the alley was only 20 yards from where we were, intersecting the next bay.) Therefore I decided to go back the way we had come. Accordingly the patrol about turned, and there was no need to ask them to hurry. The mopping up of the enemy post was accomplished in less than three minutes.

Felt rather elated, as we hurried back with our captured gun and three prisoners, to think that we had made a success of the job. The incident would give me more prestige among both officers and men, a thing I have rather lacked heretofore.

At the junction of Martinique Alley and the other communication trench, we found Baldie's party awaiting us, and stopped there for a breather. Baldie still believed that he had reconnoitred his allotted portion of Brunehilde and Attila trenches, and my statements to the contrary failed to convince him. One of his men told me he had brought the old moke back some distance and left him tethered in a wide bay, having given him a bundle of grass to go on with.

Baldie's patrol had gone out along the trench to the left some distance, and had found another starved horse, a chestnut. They met no opposition from the enemy.

After a short rest, we moved on again. The prisoners had now quite regained their composure, and one of them drew attention to the fact that he was wounded. We halted while one of the lads attended to him. A bullet had cut out a furrow in his arm. Some of the boys were bent on "ratting". One of the prisoners had a gold ring which, his pal intimated in broken French, was a gift from his fiancée. I told him to put it down inside his boot, otherwise someone farther back would be sure to grab it. One had a purse chock full of silver and a lot of German notes, and one of the boys was greedily anxious to appropriate the purse and contents. I felt sure that the Hun would not be allowed to keep it for long in any case, but it was not for me to rob, or countenance robbery of, personal property. Gave it back to him, and told him to put it in his boot. He took a 50-mark note out and gave it to me.

Arriving where the trench was garrisoned, on the right of Becquincourt, by our men, we were greeted with ardent expressions of admiration. "Good on you, Mr. Smythe; good on you, lads", they said, as we passed.

When we got to Hqrs. and I went down the dugout to report, Major Ellwood grasped my hand and exclaimed, "Well done, Smythe! You've done good work today". Most of the officers there came and congratulated me. It seemed to me that they rather overestimated the affair, considering I had only done what I had been told to do. This is the first time I have been out on patrol. It was more due to good luck than good management that we were so successful. Had the German sentry been alert at his post, and been awaiting us with the machine gun ready to enfilade the trench as we approached, there might have been a different tale to tell.

The prisoners, it turned out, were of the 2nd. Guards division. One of them, a corporal, was a sensible decent sort of fellow, and quite friendly. The other two were inclined to be sullen. "A" coy's. patrol met with resistance in front of Assevillers, and had one man wounded.

Had a good hot dinner of stew. The companies were about to go forward to occupy the line of trenches between Herbécourt and Assevillers. The plans had been altered again, and "C" coy. was now to stay in Support. Baldock, with "B" coy., was to go up and occupy the portion of Attila trench that I had reconnoitred for "C" coy. He was a bit doubtful about getting there all right without a guide, so I undertook to show him the way.

"D" coy. moved up along the communication trench in front of us. We followed very slowly, but were frequently held up on account of "D" coy. stopping. Eventually their progress was definitely arrested. Going forward to investigate, I found the head of the company had reached the junction of Martinique Alley and the unchartered trench on the left. Captain Ball was at a loss where to take his men. It was plain to him that Baldie was mistaken about that being Brunehilde trench. I suggested that a few of us go forward and make sure of the position before taking the company up.

Tonto agreed, and he and Baldie and I, with several men, set out. Passed the trees, and worked slowly forward. We had to climb over a number of disused stables. A fingerpost appeared over the crest of the rising ground some distance ahead. That must be the Brunehilde crossing, I decided, and persuaded Tonto, who was beginning to get doubtful about finding our goal, to come forward. At the fingerpost we found a trench going off to the right, but none to the left. The others reckoned that we must be on the wrong track altogether, but, referring to the map, I observed that Brunehilde trench did not cut straight across Guadeloupe Alley, the point where it cut off to the left being some little distance farther on than where it came in from the right. Assuring the others that we should find the object of our search thirty yards ahead, I persuaded them to come on, leading the way myself.

"D" coy. only had to occupy Brunehilde trench, not Attila, on the left of Guadeloupe Alley. Was feeling confident that at last we were about to get things settled, when, turning a corner, I again surprised myself and the enemy with an unexpected meeting. Two Huns were standing talking in the trench just ahead, probably at the junction of Brunehilde. At sight of me, one of them jumped back with a startled cry. I didn't stop to argue, but lost no time getting back around the corner. Evidently thinking something was wrong, the others began to beat a hasty retreat.

I shouted to them to stay and fight, but several of the men immediately cleared out, leaving only five of us, three officers, a serjeant, and one man. We retired along the trench, but still I tried to persuade the others to stay and fight. Tonto, however, thought it unadvisable, considering that three of the five were officers. Anyway, it would have been rather risky with such small numbers, when there was the possibility of being outnumbered three to one by the enemy.

Bullets from the Hun post cracked overhead, and a machine gun began to sweep the surface of the ground about the trench with its deadly fire. Arriving where the forward stable blocked our way, I said, "We'll have to stay and fight now. We can't cross round over the top under that fire". But, when I saw there was not a rifle among the five of us, and only three revolvers, my heart fell. The digger who had stayed with us had thrown several Mills bombs to cover our retirement as we came along, and they probably prevented the Huns from following us.

Captain Ball thought it was just as well to take the chances out over the top as to stay there. He got out of the trench at one side and the serjeant at the other, and they got safely through the hail of bullets to the other end of the stable. Then Baldie made a dash for it, and got through. I went next, followed by the digger. Most of the other stables and dugouts were partly broken, and we managed to get through without getting out of the trench, except one near the last, but by that time the machinegun fire had slackened off considerably. We all got safely back to the Martinique junction.

Tonto Ball and Baldock held a conference, and were undecided what course to take. They asked me for a suggestion, so I advised sending a fighting patrol up Martinique Alley and then along Brunehilde trench to the Hun post, which they would mop up forthwith. I undertook to guide them as far as Brunehilde, as it was getting dusk and I knew the way that far.

A strong patrol was soon made up, with a capable serjeant in charge, taking plenty of bombs and a Lewis gun. I guided them to the Martinique-Brunehilde crossing, as arranged. Darkness was rapidly setting in as I returned along Martinique, through its tangled growth of weeds. The excitement and nerve-strain of the day's events were beginning to tell on me, and I needed rest and sleep.

It was quite dark when I got back to where the two companies were still patiently waiting. Occasional spasmodic bursts of fire from the Hun machine gun disturbed the stillness of a calm evening. Left Tonto and Baldock to return to my own company. After going a considerable distance, I became doubtful about having kept to the right trench. The darkness was now intense. In daylight my sight is none too good, though the glasses help, but on a dark night they are useless and I'm little better then a blind man. There was the danger of having got into the wrong trench, and thus wandering into the German lines. Kept on going, however, and eventually recognised, with much relief, some of the dug-outs that blocked the trench near Becquincourt. Stepped along quickly, stimulated by the prospect of a good sleep.

"Halt!" I struggled with my memory to dig up the password. At last I got it. "China!" Silence for a second, then a friendly reply, "Its all right, digger. We didn't know the password ourselves, but we thought we'd better challenge."

It was a great relief when I climbed wearily down the broken stairway of the Hqrs. dugout, at half-past ten. Explained the situation to Major Ellwood. Lay down on a pile of straw, but I was so utterly tired that I could not sleep. My mind kept wandering over the dreaded Ifs and Might-have-beens of the day. The major was in telephone communication with Baldock and Captain Ball, and frequently referred to me to check information got from them. On one of these occasions, Captain Ball's statement was at direct variance with mine, and made it look as though I had lied to get credit for what I had never done. The major's face clouded. I again explained exactly what I had done, but he made no reply. I went away and lay down, unhappy to think that Tonto, probably the best friend I've had in the battalion, a man with a big white heart in spite of his course jests and outward vulgarity, should have unwittingly done me such an injury. He certainly would not intentionally have made an incorrect statement, but he had evidently got the different trenches confused in his mind somehow. A little later I heard the major ring up Baldock and question him about the same thing. Baldock's statement corroborated mine, where-upon the major rang up Colonel James at Rear Bn. Hqrs., and asked him to send Captain Ball away to a school, as he needed a rest from the line.

Tried to sleep, but it was a hopeless task. Just before midnight, an order came over the `phone for "C" coy. to occupy the portion of Attila trench on the left of Guadeloupe Alley, "B" coy. being in the same trench on the right, and "D" coy. being in the left part of Brunehilde, and in Arrivée. We were to be all ready in position for the 7th. Brigade to advance through us at dawn.

Thursday, 29th. One platoon of "C" coy. was away on a ration fatigue. Sedgwick got the other two platoons together, and it fell to my lot to act as guide again, as I had been up, and knew the way. The darkness of the earlier night had now given place to bright moonlight. We proceeded very slowly, as there was plenty of time and the men had a lot of weight to carry.

"D" coy. were in Brunehilde trench when we arrived there. The patrol that went out earlier in the evening had met some Huns in Brunehilde between Martinique and Guadeloupe, and were unable to get through. Later it was found that the enemy rearguards had faded away as they did last night. Probably there would be none of the enemy in the trench we were going to, but it was possible that they had left a post behind to surprise and harass us.

Going on, we came to Atilla trench, which I recognised by the place where my patrol had mopped up the Hun post, only a few yards up to the right. I led the company around the bays and traverses of Attila trench to the left. At every corner the bright moonlight made deep shadows into which it was impossible to see. A hidden enemy could have taken toll of us at will. Leading the way, I found the strain on my nerves very great, after the stress and excitement of the previous twelve hours. It was an intense relief to my mind when at last we had gone as far along the trench as orders required, and thereupon set to work to organize the trench for defence.

When everything was settled, I went along to have a look at the post where we had taken the gun and prisoners. The dead Hun had been taken away. He was dead, or they would have taken his respirator with him. Went back to my platoon, rolled up in my overcoat, and drifted into sound slumber.

Awoke at daylight and found the morning very chilly. Someone came along with the order to "Stand to". It was rather a bore, for I had only had a couple of hours sleep. Another order came for "C" coy. to go forward at once on the battalion frontage, and get in touch with the departed enemy. Sedgwick went back to "D" coy. to ring up Bn. Hqrs. about it.

Some movement was noticed away out in front, and, with the aid of my field glasses, we could see that there were small bodies of Australians moving forward, probably from the 5th. div. on our right. The sun came up in a cloudless sky, and it turned out a glorious sunny morning. The batmen with our rations had not arrived this morning. Had to go without breakfast, save for a crust of bread and jam I got from a serjeant.

Sedgwick came back with the advance orders unmodified, and we went forward, at about 8 o'clock, in a line of sections in single file, covering a front of about six hundred yards. We moved steadily across the wide valley in front, and up on the low ridge on the right of Flaucourt. A thick wide barrier of barbed wire entanglements extended along this ridge, and we halted there for some time. While waiting there, the 7th. Brigade came up and advanced through us, over the ridge.

Getting through the wire barrier, we continued the advance down the slope beyond. We were privileged to see a rather unique spectacle, which is not too common in these days of modern trench warfare. The whole countryside for miles and miles, as far as the eye could see in any direction, was covered with little files of men, all moving steadily eastward, and looking, at a distance, like so many caterpillars. It was the British army, following in the wake of the retreating Hun. A lot of machine-gun fire was going on somewhere beyond the next ridge in front, and from that we knew that the leading troops were in touch with the enemy. Artillery scouts and patrols galloped forward to find suitable positions for their guns. Some field guns and loaded machine-gun transports pushed forward over the Flaucourt ridge and into the valley beyond. Enemy shells began to fall on the ridge in front. Some flew high, and came over with a crash into the valley.

We moved across the valley and were advancing up the next slope, when the company were halted again. The batmen had turned up with our rations. After a belated breakfast, Sedgwick and Graham and I went forward to the crest of the ridge. A few hundred yards away to the right, several mules were left tethered on the top of the high ground. Fritz had evidently spotted them, for he began to pour shells over, ploughing up the ground all around them. I felt pretty mad at the cowardly drivers who had gone away and left the helpless brutes tied there exposed to the enemy fire. Eventually they managed to break loose, and bolted away down the valley.

Just beyond the summit of the ridge the German heavies were falling, with an awful crash at each explosion. Some of our own heavy howitzers opened fire, and, to our amazement and disgust, their shells fell on the ridge in front and mingled in the barrage from the German guns. A battery of field artillery drew up on the rearward slope of the ridge, and slewed around into position ready to fire.

We went back to the company, and Sedgwick sent a message to Bn. Hqrs. for orders. He had been expecting to receive an order to come back when the 7th. Brigade went through us. Retiring to a trench in the bottom of the valley, we settled down to rest there while awaiting orders. There were some deep German dugouts in the trench, and we made Coy. Hqrs. in one of them. Found in it a German book containing a number of rather unique and artistic pen illustrations. Tore them out and put them in my haversack.

Lay down on some straw and slept for about an hour. Then a runner arrived with an order from Bn. Hqrs. for the company to come back to the battalion. The order to return should have come to us when the 7th. Brigade went through.

The company fell in, and we went back to Attila trench. Heard that the Huns had been hustled in their retreat and had been pushed to the Somme. That report was soon confirmed by pontoon bridging trains moving up towards the front along a road near by. Captain Bowdon arrived back from leave, and took charge of "C" coy. There was another reshuffling of officers, and I was allotted back to "A" coy.

After we had lunched and rested for an hour or so, the battalion moved off through Herbécourt to some trenches between the village and Mereaucourt Wood. There I rejoined "A" coy. News came through that the English are making great progress in the Arras sector, advancing towards Douai and outflanking Bapaume.

Commenced writing a letter to Dorrie, but was so very tired that I eventually had to leave it till the morning. Turned in on the nice straw floor of the comfortable dugout Fritz had left us.

Friday, 30th. Slept in till half-past eight, a bit of a change after the last few days. Heard that I had been recommended for a decoration for yesterday's mopping-up stunt. Could not find the half-written letter to Dorrie, so started another. With the mail today there came the parcel of Navy Dressing from my little girl, with a nice note enclosed, but the letter I was expecting from her did not come. Got a letter from Vern, saying he is attached to the 31st. Division for three month's staff training. His leave will be due in three week's time. A letter from Mrs. Morgan, with two from Mum enclosed, dated June 9th. and 16th. They had received Bert's deferred pay, about £60. Mrs. Morgan said that Viv had called there on his way to Trentagh. There was also a letter from Eliza Prigg.

This afternoon the colonel called the officers and N.C.O's. together and held a conference. Reviewing the work of the past few days, he said it was very unsatisfactory, and was characterized by an almost entire absence of brilliance or initiative on the part of the individual officers and N.C.O's. He was very angry about several incidents where the men got "windy" and brought back scare reports; also several occasions where men deserted their leaders and their comrades when in a dangerous situation. He commended "A" coy. for the way they had advanced their line towards Assevillers, and gave "C" coy. entirely unearned credit of being the first to reach the summit of the ridge beyond Flaucourt, whence we could look down over the valley of the Somme. He also said that "a very brilliant piece of work" was done in mopping up a Hun post in Attila trench.

Referring to our next move, the colonel said we were to make an attack on Mont St. Quentin, the fortified ruins of a village on a height overlooking Péronne. Representatives from each company would go forward now and make a reconnaissance of the ground we were to advance over, as far as the Somme near Clery-sur-Somme, where pontoon bridges were to be thrown across the river by Engineers when the brigade advanced. We were to move up tonight or in the morning.

Bill Gow and I went from "A" coy. on the reconnaissance, and the whole party moved forward over the ridge to our left front, to a position in an old trench overlooking the Somme. Both German and British shells were sending up clouds of dust and smoke from the hills around Clery, almost opposite us across the Somme. We could see over stretches of country extending for many miles beyond the river valley. Mont St. Quentin could be seen in the distance, a commanding wooded hilltop, which looked as though it would prove a difficult position to storm. A little further to the right, part of the outskirts of Péronne were visible beyond a bend of the high river bank. Through our glasses we inspected the ground to be advanced over, a very superficial inspection.

While we were returning, some limbers and an ambulance wagon came up over the ridge. The Huns caught sight of them, and a battery of "whizz-bangs" gave them a lively time for a few minutes until they were able to gallop out of sight below the level of the ridge.

Just as we got back to our lines, a message came from Hqrs. saying that there would be no move tonight or tomorrow morning. We had a supper of eels that were got from traps left behind in the river by the retreating Huns.

Stayed up till after midnight finishing my letter to Dorrie.

Saturday, 31st. At half-past eight, while we were yet in bed, a runner brought an order for the company to be ready to move at nine. It was not long before we had dressed, breakfasted, and packed up ready for departure.

Jack Newton arrived back this morning, and came to "A" coy. That brought our strength up to five officers, Bill Gow commanding the company; George Ingram, Mr. Courtney, and myself, in charge of the three platoons, and Newton acting as a "spare part". Jim Collery, a splendid soldier and a reliable man, was my platoon serjeant.

Wrote a Hun postcard to Vern, and one to Mrs. Morgan. Packed up some of my souvenirs, including a postcard photo of one of the prisoners we had taken on Wednesday, and addressed them to Dorrie. Gave the packet to Mr. Wells to post for me.

Orders came to move at half-past ten. Heard that the 5th. Brigade had advanced to Mont St. Quentin. We left the trench lines and moved off over the ridge, with intervals between platoons, going down into the Somme valley below Cléry. There was a pontoon bridge over the canal, and a boarded foot-bridge across the marshes. The scenery hereabouts is beautiful. A wide flat valley between steep hills is covered with marshes and swamps, intersected by canals and clear streams, and there are just sufficient trees to form a pleasing variety.

Crossing over, we formed up into artillery formation on some flat ground, and awaited orders. A battery of six field guns came into action just in front of us, and hurled no end of "iron rations" over to Fritz.

After waiting some time, we moved on around the guns and advanced along the flat, following the railway line. Before retreating, the Huns had systematically destroyed this line, having blown it up with a charge of high-explosive about every twenty yards. Hardly a rail was left intact. As we moved in artillery formation along the strip of flat ground below the hill on which Cléry is situated, the village was being subjected to a rather heavy bombardment from all calibres. It made one look askance, with a sort of nervous twitch about the heart, at the significant clouds of black smoke and red brick-dust that kept spurting up from among the ruins. Some of the shells, the fringe of the bombardment, came over the hill and made the flat look untidy, a number of them also falling in the water and shooting up tall jets of spray, like artesian bores. These latter were practically harmless, but a few fell uncomfortably close to the railway line, which we were following.

Getting past Cléry, we rested awhile under a steep bank which rose up like a small precipice from the roadside. Pushed on again and came to a definite halt under the shelter of a long chalk bank, where the lower portion of the hillside had evidently been cut away to accommodate the Albert-Ham railway. There we lunched, and then proceeded to wait developments. No.1 Platoon, under George Ingram, was sent forward to reconnoitre the positions we were to occupy.

Members of the 24th Infantry Battalion resting on their way to the front line,

Members of the 24th Infantry Battalion resting on their way to the front line,

after crossing the Somme in order to join in the operations at Mont St Quentin 31-8-18. AWM

The enemy continued his spasmodic bombardment, though at times he left us in peace for half an hour at a stretch. Besides high-explosive, quite a lot of gas shells fell into the river marshes. The spot where the heaviest shelling took place was at the far end of the chalk bank, near Cléry, where the road crossed the railway line to run across the marshes to Omniécourt-les-Cléry.

After we had been waiting for several hours, orders were issued for us to move forward and occupy Gottlieb trench, which is about a thousand yards from Mont St. Quentin. Before we moved, Jim Donnelly arrived on the scene with a bag full of cigarettes, which he distributed among the boys. No.1 Platoon got back just in time to guide us up. We went forward in platoons around the chalk bank, and along the railway line to Lost Ravine, then along a trench and through some great deep quarry pits, and back to the railway where it ran along under a steep bank. Shells were bursting in the valley in front. A few machine-gun bullets occasionally whipped the air around us. We halted awhile under the bank, where a lot of rolling stock and permanent railway works had been thoroughly demolished.

Bill Gow decided to move the company forward in parties of four men at a distance of 100 yards between parties, a very sensible proceeding, I thought. Told my platoon off into five parties of four men each, and, when the last of the preceding platoon were well away, moved forward with the first party. Going down the road that runs to the right of Brasso Redoubt, we got across into the right communication trench of the redoubt. Progress was slow and stoppages frequent. A wide valley lay between us and the dominating hill of Mont St. Quentin, which frowned at us from its wooded brow, as though resenting our approach.

As was only to be expected, the enemy caught sight of some of us moving forward, and began to waste some of his spare ammunition on us. They were the dreaded "heavies", probably eight or nine inch, and as each one crashed with its awful blasting roar, it was enough to make the bravest heart tremble. Fortunately there were not very many of them. There appeared to be only one howitzer firing. One of these ugly monsters exploded about twenty or thirty yards from where I was in the trench. It was quite close enough for my liking.

Arriving at Gottlieb trench at last, I was met by Bill Gow, covered with white chalk-dust from head to foot. He told me that the sjt.-mjr. was dead. Poor old Jock Love, he had just been killed by one of the heavies, which fell in the trench. A man, whitened with chalk-dust, crawled painfully around a corner of the trench, badly wounded. It was one of our batmen, Richardi, but I failed to recognise him at the time, and did not know till afterwards that it was he. Corporal Woods was also wounded, and another man killed, the one shell having claimed four victims.

Took my platoon along Gottlieb trench to the right and organized the position for defence, with half the platoon on either side of the road. There were a couple of deep German dugouts in the trench here. They would prove useful in the event of a heavy bombardment from the enemy. A Machine Gun Coy., with their Vickers guns, came along and occupied the trench on my right, as far as the railway line. They are attached to "A" coy. for the stunt.

The situation was, to put it mildly, vague. Just where the enemy were, we did not know; but a lot of machine-gun fire came from the high ground in front, which was supposed to have been captured by the 5th. Brigade. We were also subject, at times, to enfilade fire from the right. Save trench, which runs parallel with Gottlieb, a hundred and fifty yards in front, was said to be occupied by the 23rd. Bn., but even that seemed uncertain. Who was holding the line on our right flank, or whether it was held at all, was a mystery.

Heard that Bill Graham was rather badly wounded during the shelling along the chalk-bank this afternoon, a piece of shell-casing having entered his back and penetrated one of his lungs.

Had just got my platoon settled down in the trench, about dusk, when Jim Collery came along and remarked that there were a lot of dead and wounded lying in a heap together in the trench beyond the left of "A" coy. He thought they were 18th. Bn. men, and reckoned that the lives of some of the wounded might be saved if they were taken away to a Dressing Station. I asked him were there no stretcher-bearers attending to them. "No", he said, "not a soul near them, not one of their own men even. They have just been left as they fell." "Good heavens!" I said, "we can't leave wounded men there to die." I hurried along the trench to the left, followed by Jim.

Fortunately I knew what to expect, and was therefore prepared for the scene we came upon. It was the kind of thing that leaves its impress stamped on the mind for ever. A heavy, probably a 9.2 inch, had evidently landed fair in the trench. The carnage was awful. Dead, wounded, and dying, all lay huddled and twisted together in grotesque little heaps, a mass of mangled flesh. At first all was silent. But when those who still lived saw that we were there, they began to moan piteously for help. Without any hesitation we set to work to do what we could for them. Kneeling down by the first living man, I saw that he was in a pretty bad state. Besides other wounds, his right arm was hanging to his shoulder by a small strip of skin and flesh. He begged me to cut the useless limb right off, and I tried to do so with a blunt jack-knife, but could not manage it. I cut his tunic away from the damaged arm, and cut the equipment off his body to give him a little ease. A couple of stretcher-bearers came along, and I got them to take him out. The next living man had both knees completely shattered. He seemed very weak from loss of blood, and kept asking, "How are my legs? I can't feel them." We assured him that he would soon be all right and that the stretcher-bearers would be along presently to take him away. We could do nothing for him except to cut his equipment away and thus give him a little ease before he should drift off into "the sleep that knows no waking." Another poor fellow lay across the trench, with one arm badly wounded and a leg broken in two places. A man beside him was literally covered with wounds, but was quite cheerful in spite of it. Near these two, another poor wretch lay back against the side of the trench. The raw torn flesh showed where both legs had been blown off at the knees. His right arm was shattered from wrist to shoulder, a mass of bloody pulp. His mouth was badly broken and his head and body were covered with blood. Yet he was quite conscious, and kept asking plaintively, "When are they going to take me away?" I cut his equipment away and assured him that he would be got away as soon as stretcher-bearers were available to take him. There were also other wounded there, including one man with several wounds in his legs and a gash in the temple, from which the blood had poured and covered all his face. We did not stop to look at the dead, many of whom lay in the trench all mixed up together.

George Ingram appeared on the scene, and he and Collery and I, with a stretcher-bearer, attended to the wounded as best we could, bandaging the smaller wounds with field dressings. Most of the wounds were large, requiring surgical treatment, and with those we could do nothing.

Darkness was fast setting in. I had sent for more stretcher-bearers, but they seemed to be all away with wounded. At last two arrived with a stretcher, but they needed more men to help them. I sent along the trench, and, after a little difficulty, got a few men to come and assist. They took one of the less badly wounded men, whose life could be saved by prompt treatment.

The man who was covered with wounds, but still cheerful, complained of being cold, so we covered him over with ground-sheets that we got from some of the dead men. The unfortunate fellow beside him, with both legs off and arm shattered, continued to plead, impatiently. "When are they going to take me away?" He wanted to smoke, but could not hold the cigarette in his broken mouth. The man who had both knees shattered complained bitterly, saying that if only he could get hold of a rifle he would blow his brains out. Poor beggar, it would have been better had he been killed outright in the first place.

At last some stretcher-bearers arrived, and we left the wounded men to them. It was now quite dark. In order to establish the identity of those who were killed, I set about getting the books and papers from their pockets. In a corner of the trench a number of corpses lay in a tangled heap together. It was impossible to make out just how many were there, but there were four who could be got at. One of them was sitting in a huddled position with his right arm outwards. On his sleeve were the three chevrons of a serjeant and the 24th. Bn. colours, with the brass "A" for Gallipoli. I wondered if he might be someone I knew. It appeared that several of the victims were 24th. Bn. men, and it was also said that Mr. Martin had not been seen since the shell exploded in the trench. He was believed to be among the killed.

I groped around the necks of a couple of the dead men to get their identity discs, but they apparently did not have any. While doing so, I noticed that one was quite warm around the neck, and thought that probably he was alive, though unconscious. I felt his leg, where the clothing had been torn away, but it was quite cold. Then looking closer, I saw a great gaping hole from forehead to crown of his head, and the skull grated where it had been split from top to bottom. It made me shudder, although I've grown rather callous to such things. The skull was empty and hollow, the man's brains having been blown out.

I took some books from his pockets, as well as from those of the man beside him. The next victim was half-buried under the others. While trying to release him enough to get at one of his pockets, I felt a star on his shoulder, and concluded that it must be Martin, forgetting at the moment that he was a first-lieutenant. I obtained some of his books, including a bible, and also got some books and papers from a couple more, farther along.

Took them to the dugout in my section of the trench, and Jim Collery and I looked over them by the light of a candle. Opening a pay-book, I saw the name "Pte Newton" on the name page. Closer inspection, however, showed the "Pte" crossed out and "Cpl." written instead. Another glance sufficed to show that the "Cpl." had been replaced by "Sjt." For a moment we wondered who "Sjt. Newton" was, and then I saw the "Sjt." also had been crossed out, and on the line below was "2nd.Lt." "Good God," said Jim, "it's Mr. Newton!" It was. Cheery, curly-headed Jack Newton, who left Fovant with his commission a few weeks before I did, and who only rejoined the battalion this morning, after being away at a school or somewhere.

Opening another pay-book, we were amazed to see the name "Doble". Brave little "Snowy" Doble, a runner, whom only yesterday Bill Gow had recommended for the D.C.M. We also identified Pte. Ellen of "A" coy., and Pte. Martin and L/cpl. Robertson of "B" coy. We had yet to find out who the serjeant was. We had all the books grouped according to the names they bore, except a wallet containing about thirty or forty photos. Jim suggested that it might be Vic Jolly's, he being an old Gallipoli serjeant. I hoped he was mistaken, for Vic was such a jolly decent sort of a chap. The first photo in the wallet was of an old woman, a snapshot photo taken in a garden. Jim said he believed it was a photo of Vic's mother, which had only come with this morning's mail, and which Vic had shown to the other serjeants when he got it. Turning the photos over to look for some address on them, I at last came to one which commenced, "To Vic....." That proved that the Anzac serjeant was Vic Jolly.

I tied the books and things up in separate bundles to hand in to Orderly Room that they might be sent to the relatives of the men who were killed. Jim Collery said that Murray and another man were missing, and it was thought that they were also blown up by the shell that got the others.

Some mail came up with the rations tonight, and I got a long letter from Dorothy, eleven pages, written last Sunday. Read it over more or less absently, my mind being rather shaken in consequence of the evening's tragedy.

Went along to Bill Gow's dug-out to discuss the situation. George Ingram only had eight men left in his platoon, so it was decided that they should act as a carrying party during the attack on Mont St. Quentin. No orders for the attack had come to hand as yet. Murray's body had been found lying outside the trench where the other dead men were. He had been blown right up over the parapet. It was now practically certain that Mr. Martin was also amongst the killed. No trace of him could be found, and it was therefore concluded that he must have been blown to pieces.

(Afterwards, when the bodies were buried, all that could be found of Martin was half the cover of his pay-book.)

SEPTEMBER 1918

Sunday, 1st. Wattle Day in Australia. Did not try to get any sleep during the night, there being so many things to be attended to do. As the hours dragged by and no attack orders were forthcoming, we came to the conclusion that the operations had been postponed. The situation on our right flank was rather obscure, and it was even reported that the Germans were still in occupation there.

At about 4 o'clock a runner arrived with orders to attack in the morning. Zero hour would be notified later. "C" and "D" coys. were to be the first wave to attack, "A" and "B" to follow in artillery formation at 100 yards distance. Our objective was Tortelle Trench, about 1,000 yards beyond Mont St. Quentin. "D" and "B" coys. were to advance across the flat on the left, mopping up the little village of Feuillaucourt on their way, their left flank moving along the Canal du Nord. "C" and "A" coys. were to take in the northern outskirts of Mont St. Quentin in their advance to Tortelle trench, and the 23rd. battalion, operating on our right, was to go through the main part of the village.

We all felt a bit dubious about our chances of success. Our starting-off position was so uncertain. However, we would muddle through somehow, and do the best we could. Colonel James rang up from Bn. Hqrs., which was back in Lost Ravine, and said that the 23rd. Bn. had reported that the enemy were in the right portion of Gottlieb trench and also in Holm trench. He asked me to send out a patrol to find out definitely if there were any Germans in the trenches on our right.