England and Marriage

MARCH 1919

Monday, 17th. Arrived at the station just in time to catch the 8.40a.m. train to Charleroi, arriving here after about an hour's run. There was quite a bundle of letters awaiting me, including one from Vern from Colombo. They were not allowed ashore at Port Said or Suez on account of influenza on the land.

The debris after the blowing up of three trains at Charleroi by the enemy,

The debris after the blowing up of three trains at Charleroi by the enemy,

three days after the armistice. AWM

Found out today that Hassall's Art School is included in the educational scheme, so I put in an application for it. Viv told me he had got a letter from Mrs. Hyndman saying she had had a cable that Vern and Mary had arrive at the quarantine station at Sydney.

Saturday, 22nd. Nothing much to record during the week. On Tuesday I asked the adjutant for the next investiture leave to England. At present all leave, drafts, and moves to England have been suspended until the strikes are settled.

Saturday, 29th. Another week of little event. For the last three days we have had very wintry weather, alternately snowing, raining, and sleeting. This morning there was over an inch of snow on the ground.

Viv's promotion to the rank of Temporary Major came through today, and was made the occasion for a little jollification in the mess.

Sunday, 30th. Arranged to go to Bullecourt with Whitear tomorrow, as I have wanted for some time to go and see Bert's grave, or at least the spot where he was killed.

Monday, 31st. Made all the necessary arrangements this morning to go to Arras by the Cologne express. Got everything ready, and then Whitear found he couldn't come, as he had been put on some job. Decided that I must go alone and not put if off any longer, as my investiture leave might come through at any time now. Then Viv came along and told me I couldn't go as my investiture leave was already granted and I must be in London before Saturday. Felt very disappointed, as I had set my heart on going to Bullecourt. Will probably leave tomorrow for England. The chances are I shall not return, but go on with Hassall's School of Art at the end of my leave.

APRIL 1919

Tuesday, 1st. April Fool's Day. The Belgian girls around the billets amused themselves with blue-bags, which they rubbed over the faces of all the diggers they met. It appears this is the usual manner in which this day is celebrated here.

My leave pass did not come today, being delayed at brigade. Packed up my belongings ready for departure.

Wednesday, 2nd. The leave pass came through this afternoon. Was disappointed to find it was only for four days instead of fourteen as I had expected.

Left Charleroi about six o'clock by the Cologne-Boulogne express.

Thursday, 3rd. Had a good trip down, arriving at Boulogne about eight this morning. Breakfasted at the Officers' Club, and caught the morning leave boat, sailing from Boulogne at half past ten. Got across to Folkestone in good time, and arrived at Victoria at half past three. Went straight out to Hounslow, to Mrs. Morgan's.

Boulogne

BoulogneFriday, 4th. Went in to Hqrs. today and arranged about attending the Investiture at Buckingham Palace tomorrow. Also arranged to start at The London School of Art on Tuesday.

While in town I went to the Grafton Galleries to see the "War in the Air" exhibition of photos. They are nicely coloured, and there are some very fine pictures amongst them, but nothing very exciting in the way of aerial combats. Still it was very interesting, and well worth a visit.

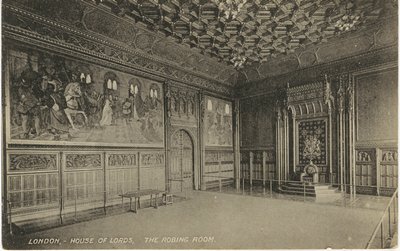

Saturday, 5th. Went in to Buckingham Palace about ten o'clock. Quite a lot of officers of all ranks were arriving for the investiture. We passed through various rooms, all of which were rather plain and inartistic, into a large vestibule, where we were kept waiting about an hour. There were about 150 officers in this room, all to be awarded the Military Cross. The V.C.'s and D.S.O.'s were in a room separate. When they had all gone through, the M.C.'s at last got started. The senior ranks went first, and when it came to the lieutenants we were taken in alphabetical order, so naturally I came near the last.

We filed out in to a long corridor with a fine heavy carpet and beautiful marble statuary, up a flight of stairs and through another passage with large mirrors and portrait paintings of various European royalties on the walls. Crossing the rear end of the investiture room, we came along another corridor to a large doorway opposite to the dais upon which the king stood. This dais was at the end of a large hall, in which the visitors were seated. An orchestra entertained them with various selections.

When my turn came I walked forward and approached the dais, and halted before the king. He was dressed as a staff officer, and looked considerably older than I had expected, his face being quite wrinkled. I had also expected to find him looking extremely bored after having awarded about two hundred decorations, but, on the contrary, he appeared to be quite interested in his task. In fact, he seemed to be somewhat amused at the proceedings. Fastening the silver cross, with its purple and white ribbon, upon my tunic, the king said, "I am pleased to give you the Military Cross for your services." I replied, "Thank you, sir." The king shook hands with me. It was a warm manly handshake. Then I stepped back, turned, and went out through a doorway at the opposite side of the hall.

Leaving Buckingham Palace, I went down to Waterloo and caught the 1p.m. train to Andover. Dorothy was very surprised to see me, as she was not expecting me over so soon.

Sunday, 6th. Made enquiries today and found that we cannot be married under English law, unless Dorothy has her father's written consent. Tonight I broached the subject again to Mr. Jewell, but it was useless to try to argue with him. When I told him we would go to Scotland, where parents' consent is not required, and be married there, he said, "Well, if Dorothy goes to Scotland, she won't come back here!" So that ended the discussion.

Saturday, 12th. Returned to London from Andover on Monday, and started work at the London School of Art on Tuesday. "Wilbur" Wright, the art editor of our Cambridge magazine, "Cheerio", is one of the students. There are quite a number of Australian soldiers at the school. There are many girl students, most of whom smoke a lot of cigarettes.

I was very fortunate in getting board and lodging at a house in Earl's Court, about twenty minutes walk from the school. The tariff is £2-2 per week, which is as cheap as one could get anywhere, and the food is good and plentiful.

John Hassall came to the school on Wednesday (he comes only once a week), and he very favourably criticized some of my former work. Work at the school is divided between life, portrait, and poster classes.

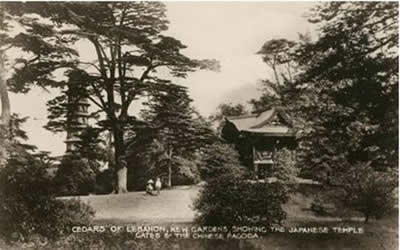

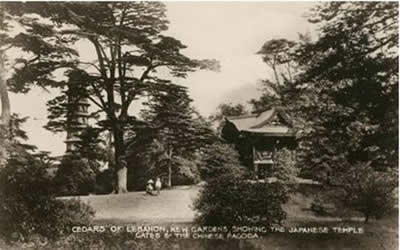

Saturday, 19th. Arranged for Dorothy to come up to London for Easter weekend and stay at Mrs. Staddon's, as there happened to be a room vacant. Got some home mail on Tuesday. They were expecting Vern and Mary to arrive at Sydney next day. Poor old Mum was wishing for Bert to be coming too. Yesterday I went out to Richmond for the afternoon, and strolled up along the bank of the Thames. It was a bright sunny day, and many boats were out on the river. Walked right up to Kew Gardens, which looked charming in their spring freshness. It was a treat to bask in the warm sunshine and gaze on the fresh green landscape, after the past few months of severe winter. Quite a lot of people were out in the gardens in answer to the call of spring.

Dorothy came up to London this afternoon. In the evening we went into the city hoping to get a seat in a theatre, but it was hopeless. So we went to a cinema in the Strand.

Sunday, 20th. Easter Sunday. We went to Kensington Gardens this morning hoping to get a boat on the Serpentine, but they were all taken already, and a crowd waiting. This afternoon we went out to Kew Gardens and looked through the various hot-houses and ferneries. One of these was a very large house full of tropical trees and plants, beautiful tree-ferns and palms and creeping plants. We ascended by spiral stairways to a gallery, from which the view was like looking down through a tropical jungle. In places it reminded me very much of the beautiful valleys and gullies of Mount Comboyne, or the Gloucester Buckets, in the Manning River district of New South Wales.

The Palm-house, another large glass building but without a balcony, contained innumerable fine specimens of palms of all varieties and sizes. There were also various other glass houses, containing all sorts of flowering shrubs and plants. In one of these were some very beautiful and wonderful orchids and other rare flowers of strange colours and forms. We didn't have time to stay and walk round the grounds.

Monday, 21st. Easter Monday. After breakfast we went to Kensington Gardens and got a boat on the Serpentine. It was a lovely day for rowing. Persuaded Dorothy to try her hand at the oars, and she managed very well for a first attempt.

In the afternoon we went to see "The Maid of the Mountains", at Daly's, seats for which I had booked during the week. It was a fine play and the music was beautiful, especially Jose Collins' singing.

We went to Euston station afterwards and found out the fares and times of trains to Scotland, as we have definitely decided to go there to be married.

Saturday, 26th. Dorothy went back to Andover by an early train on Tuesday morning. The same day I wrote to several clergymen in Scotland, whose names I had got from a directory at the Guildhall, and asked them about marrying in Scotland.

On Wednesday a letter came from Viv. He expects to leave for England with the last remnant of the 2nd Division about the end of May. We want him if possible to be present at our wedding. Cabled home on Thursday for £30 of my money to be cabled to Mrs. Morgan for me.

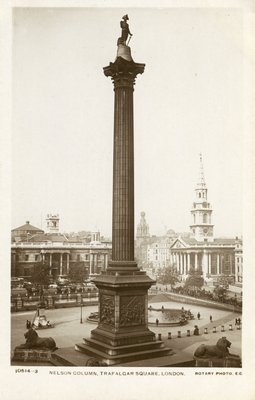

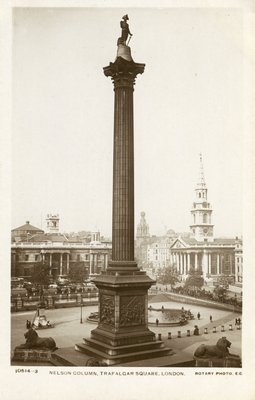

Yesterday was Anzac Day, and I went in to Trafalgar Square to see the march of Australian troops. The square was crowded, and many of the buildings decked with flags and bunting. A band and one thousand troops from each Division of the A.I.F. took part in the march besides Cavalry and Artillery. The Prince of Wales came along first in a motor car, and he was by far the most cheerful-looking individual in the procession. The others all looked more or less bored and fed up. General Rosenthal led the 2nd. Division contingent, Brig.-General Robertson also being present. There was a great deal of cheering as the troops marched past.

Some replies from Scotland came to hand today. Rev. A.J. Campbell, of Glasgow, said that parents' consent is not required in Scotland, but we must establish bona fides. Rev. Gould, of Callander, said that Dorothy would have to come to Scotland for the requisite three weeks' residence, or else have banns proclaimed at her place of residence in England. Another man I had written to wrote saying he was retired from the ministry and living at Edinburgh. Wrote to Revs. Gould and Campbell for further particulars.

Wednesday, 30th. On Sunday we had some remarkable weather for the time of year. Snow fell persistently, and gathered on the ground in thick mushy masses, while the wind blew a hurricane. It was like a fag-end of winter that had lagged behind in the march of time.

I applied for one month's special marriage leave to Scotland, but it was refused, so the only thing to do is for Dorothy to stay in Scotland for the necessary three weeks' residence, and for me to take a few days' "French" leave.

Letter from Mum today. She had had a fall and hurt her leg, with the result that the varicose veins have broken out afresh, and she has to lie up for three months.

MAY 1919

Saturday, 3rd. Yesterday I received a notification from the Commonwealth Bank that the money I cabled home for has come to hand. Also had a telegram from Rev. Campbell saying that accommodation is scarce in Glasgow, and that if I am coming today he could put me up over the weekend.

Came down to Andover this afternoon. Mr. Jewell was very nice to me, but Dorothy told me afterwards that her mother was very angry and upset over our decision to go to Scotland, and especially annoyed with me, as I "ought to have more sense".

Sunday, 4th. Dorothy and I spent the day over at Perham Downs camp, being guests of Miss Miles, at the Central Stores. While over there Dorothy gave Mr. Earle a week's notice of leaving.

Saturday, 10th. Came back to London Monday morning, after having made final arrangements with Dorothy about going to Scotland. After school the same day I went out to Hounslow to see Mrs. Morgan. She greatly disapproves of our going to Scotland, and told me so in language unpleasantly blunt. She regaled me with no end of advice, with many pessimistic prophesies of future regrets and unhappiness for our foolishness. She is a bit disgusted with Dorothy for her "lack of consideration for her mother", and even more disgusted with me to think that I could do such a "dastardly thing". I was in no mood to accept advice from anybody, and rather resented her interference, but did not say anything about it, except to tell her that experience had taught me to rely upon my own judgment rather than take advice from others. She did not ask me to stay for supper, as she would have done ordinarily, and when I left she seemed rather cold. I had gone without dinner in order to go out there, and, as the restaurants were all closed when I came back, I had to go hungry to bed.

On Thursday I got a letter from Mr. Campbell, in which he said that it is only necessary for one of us to reside for fifteen days in Scotland prior to the marriage. That means that if we keep to our original intention of marrying on June 5th., there is no need for Dorothy to go to Scotland until the end of next (week). As I had written to Mr. Campbell earlier in the week telling him that we would arrive in Scotland Sunday (tomorrow) morning, I wrote again saying that we would not come until the end of next week instead. Got through on the 'phone to Perham Downs and told Dorothy about the alteration, and she was delighted that the time of waiting in Scotland would be so much shorter.

Came down to Andover this afternoon for the weekend, perhaps my last stay here.

Tuesday, 13th. Returned to London from Andover on Monday morning. Wrote to Mrs. Jewell tonight pointing out to her the gross injustice that she and Mr. Jewell were inflicting upon Dorothy by not allowing her the privilege of marrying in her home town. By their act they were attempting to deprive her of her individuality, and were denying her the right to choose whom she would for a husband. They were trying to prevent Dorothy's happiness for the sake of their own pleasure. They were keeping from her the ordinary joys and happiness of a home wedding to which every girl is entitled at the time of her marriage. I appealed to her mother-love and sense of common justice to relent at the eleventh hour and persuade Mr. Jewell to sanction the marriage in England, or, if that be impossible, to at least give her own consent and send her well wishes with Dorothy to Scotland, which would make my little girl much happier.

It is just possible that if Mrs. Jewell relents she may be able to persuade her husband, as he has so often declared that it is only for her sake that he opposes the marriage. However, I do not entertain much hope of that, but even if Mrs. Jewell is nice to us and sends her blessing with Dorothy is would make a lot of difference to Dorrie and will take away a lot of the sadness of leaving home to be married in a strange country.

Saturday, 17th. Nothing of note to record during the past few days. Last night I packed a few necessary things ready to take with me to Scotland. Had everything ready for departure today, but, as Bobbie said, "The best laid plans of mice and men oft gang aglee". I was to meet Dorothy at Waterloo, and our plans were to catch the 9.25p.m. express from Euston, arriving in Glasgow early in the morning. Then, during the day, I was to find a suitable place for Dorothy to stay for the "fifteen days", and then return to London tomorrow night.

However, when I came in for lunch about midday, there came a telegram from Dorothy saying, "Come to Andover by 1p.m. train if possible. Affairs satisfactorily arranged." I was more than delighted to know that after all we are going to have a proper English wedding, if only for Dorothy's sake. It would save a lot of unpleasantness and bad feeling.

I missed the 1p.m. train but caught the 2.15 from Waterloo. Mr. and Mrs. Jewell had gone to Exeter to the funeral of a brother-in-law. Last night Dorothy had everything packed ready for departure, and had even ordered a cab to take her to the station, when her mother came to her and said, "I can't let you go to Scotland. Send a wire to Perce and ask him to come down here. I'll speak to your father about it, and we'll fix everything up all right. So there will be no need for you to go to Scotland." She had got no assurance from her father about it, but Dorothy has implicit faith in her mother's word, and has no doubt that everything will be all right. We were both very pleased at the prospect of being married at home and spending our honeymoon at Lynmouth, in Devon, as originally intended.

Sunday, 18th. Sent a telegram to Mr. Campbell today saying that we are not coming. Wrote to him explaining what had happened. This afternoon we took a walk out to our favourite little wood. It is very pretty now in all its glory of Spring foliage. What a pleasure it is to have the cold bleak Winter past, and the warm sunny weather here instead.

Monday, 19th. This afternoon we arranged with Mr. Tabraham about the "Grand Event". We also went to the Registrar's office to see about a special licence. Got a paper from him which must be signed by Mr. Jewell giving his consent.

Mr. Jewell arrived home about six o'clock, leaving Mrs. Jewell back at Exeter for a few days. As soon as he came in, my hopes began to sink, as he did not look at all amiable. Dorothy took the children out somewhere, and I took the opportunity to broach the subject, mentioning what was said to Dorrie by her mother. He replied that he had heard nothing about it, and that the only thing Mrs. Jewell had said to him on the subject was, "Dorothy has always made her own arrangements without consulting us, so let her go on making her own arrangements."

I was thunderstruck. The last thing I expected was treachery on the part of Dorothy's mother. Mr. Jewell went on to complain of Dorothy's lack of dutifulness, she had always opposed their wishes and had been deceitful and bad-tempered since she was ten years old. There wasn't a good trait he could find to her credit. (This was all strangely at variance with what he said over a year ago, when he declared that Dorothy had always been such a good daughter and such a splendid help to them that it would be a terrible loss to them if she were to go away). He wanted to know why was all the hurry, and why couldn't we wait for a few years. When I told him that I must return to Australia soon and couldn't afford the expense of coming over to England and taking Dorothy out there, which would cost close to £200, he said that he did not believe Dorothy would last twelve months once I were gone. He declared that neither of us knew our own minds, hadn't known each other long enough. This, in spite of the fact that we have been "going together" for nearly two years!

It was useless to try to argue with such a pigheaded fellow. His own obstinacy, if nothing else, would not let him give in or see things from a rational point of view. Of course he refused to give his consent. I felt absolutely disgusted to think of the treacherous way we had been fooled and kept from going to Scotland on Saturday. Dorothy was terribly upset when I told her. She refused to believe her mother guilty of treachery, and thinks that her father must have lied. She felt very bitter towards him for the rank injustice of his action and the unwarrantable things he said against her. I wanted her to come away with me at once and catch the midnight train to Scotland, but she would not leave the children till her mother returns, which should be on Wednesday.

Dorothy wrote to her mother saying she would leave for Scotland without fail on Thursday, unless she (her mother) could persuade her father to sign the paper giving his consent.

I came back to London by the half-past nine train, feeling bitterly disappointed at the unexpected turn of events. The attitude adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Jewell is absolutely beyond my comprehension. I cannot understand them. It seems the more remarkable when one considers that their only objection to our marriage is that by going so far away from home Dorothy would be entirely lost to them. They want to sacrifice her happiness in order to keep her for themselves!

Tuesday, 20th. Got a letter from Mum today saying that Bert's Starr-Bowkett, now kept for me because none of my earlier allotment money had been banked, had been drawn in a ballot. That means a loan of £400 free of interest, and repayable at the rate of £1 per week. It will be a great help towards getting a home.

Went out to Kew Gardens this afternoon and made a little watercolour sketch of a pretty bit of landscape in Queen's Cottage Gardens. The blue-bells are in full bloom now, making the gardens a wealth of beautiful colour.

Wrote to Mr. Campbell tonight explaining the situation in which we were placed, and saying we would probably come on Friday morning.

Wednesday, 21st. Got a letter from Viv today saying he is not leaving Belgium till the last day of the month, perhaps later. Thus it looks improbable that he can be present at the wedding. Applied for an extension at the London School of Art till October, as my time is up on June 26th.

Thursday, 22nd. Went in to Waterloo this afternoon feeling not at all sure that Dorothy would be there. I had left it pretty late before coming in, in case a telegram might come at the last minute. However, when the Andover train came in, Dorothy was there all right. Her father had remained obstinate to the last, refusing her mother's request to sign the paper. We went out to Mrs. Staddon's for dinner.

Sent a telegram to Mr. Campbell saying we are coming by the late train. Came into town and spent the evening at a cinema, theatres being impossible unless booked a week at least in advance.

We left Euston by the 11.30p.m. train for Glasgow.

Friday, 23rd. We managed to get a little sleep during the night. Daylight arrived before we reached Carlisle. Soon we were in Scotland, flying along through green undulating country, mostly pasture land. The train was late, and it was after half-past nine when we arrived in Glasgow, both feeling tired after the long journey.

We got some breakfast at a restaurant, and then hunted up Mr. Campbell's residence in West Regent Street. There was only the maid at home. Mr. Campbell was away at Edinburgh on ecclesiastical business. Mrs. Campbell had been up to meet both the early train and the one we came by, and had evidently missed us somehow. She had then gone out sketching for the morning.

The maid provided some tea, cakes, and some very nice scones, after which we went out to have a look around the town. Most of the streets we passed through were dusty and smoky and not at all attractive. We found a bridge over the river, which is a dirty muddy stream. One wonders where are the "Bonnie Banks of Clyde" that Harry Lauder sang about, but perhaps it is nicer away from the town.

Came back to Regent St., and Mrs. Campbell arrived about two o'clock. She is a jolly sort of a woman, and was very nice to us. She said it was practically hopeless to try to find accommodation in Glasgow, and offered to take Dorothy in for the two weeks. That was very good of her, and will make things much easier for us. The three of us went to a restaurant for lunch, and then looked around the town.

I had intended going back to London tonight, but altered my mind and decided that I might as well stay over the weekend. Went to the American Y.M.C.A. and booked a bed for tonight and tomorrow night.

Mr. Campbell arrived back from Edinburgh about half-past six. He is a big burly Scot, and has been a chaplain with the forces at Gallipoli, Egypt, and Palestine. They asked us to stay for dinner, and we spent a very pleasant evening there. Mrs. Campbell paints in water colours, and has some nice landscape sketches.

Saturday, 24th. Slept in late this morning. Went up to the house, and Dorothy and Mrs. Campbell and I went out to lunch, Mr. Campbell being away at Edinburgh again.

Afterwards Dorothy and I took a tram out to the Art Gallery, which is a fair building situated in very pleasant grounds, with the handsome grey university standing on a hill just beyond a deep gully at the bottom of which flows the Kelvin brook.

We went into the Art Gallery. First on entering we came into a large hall full of sculpture. It bore a striking contrast to the Musée at Brussels, for here there was nothing of the horrible or gruesome, but only beauty in its purity. Many of the pieces were very finely and delicately modelled. Several rooms were devoted to a museum, which contained a great collection of interesting things, including stuffed animals and birds from all parts of the world, and numerous skeletons, some of extinct creatures. Among the stuffed creatures was a huge Irish elk standing about eight feet high, and some very tiny birds, about the size of cicadas, or less.

From the museum we went upstairs to the picture galleries. According to my taste, they are by far the most beautiful lot of pictures I've yet seen anywhere. The wonderful deep richness of the colours is remarkable. Of the lot I liked the Old Italian School best. Did not have time to make a thorough tour of the galleries, as they are extensive, and closed at four.

We went for a ramble through the grounds, down the gully and across the brook, and through a prettily laid out park along the farther bank. We got back for dinner about half-past six, and afterwards, as there was an open-air concert being held in Kelvin grounds, decided to go to it. It was a pretty fair turn-out, some of the items being very good and amusing.

Sunday, 25th. This morning we went to St. John's Church, of which Mr. Campbell is the minister. After the service we climbed the church tower, accompanied by Mrs. Campbell and several other ladies. Some fine views of the town, including the old cathedral, necropolis, and John Knox's monument, could be had from the top.

In the afternoon Dorothy and I went to the service in the cathedral just to see the interior, as it is such an interesting old building. After an early dinner, about five o'clock, we went out to the Botanical Gardens, which are small, but very nice and pleasant.

Left Glasgow by the 9.45p.m. express, leaving Dorothy to stay, for the necessary "fifteen days", till I come again. It is all very romantic and exciting, and would be just the sort of thing I would glory in if it were not for the unhappiness caused to Dorothy on account of leaving her home and coming away to a far land to be married.

Saturday, 31st. On Tuesday a number of students from the school went out to Kew Gardens for some outdoor sketching. The gardens now are gorgeous with azaleas and rhododendrons, a blaze of brilliant colour, especially the azaleas, with their burning reds, from deep rich blood to glowing pink, their bright russet browns, and their beautiful shades of orange and yellow. Our task was to make a watercolour sketch of Rhododendron Walk, which provided plenty of brilliant colour. My effort was not too satisfactory, but, after returning, I touched it up with body colour, which made a great improvement.

Started house hunting on Wednesday, or rather hunting for rooms. They are difficult to get, and the rents are extortionate. The only place I found that was even reasonably acceptable was in Earl's Court Road, a furnished bed-sitting room on a second floor, with the use of kitchen, which was in the basement, at 35/- a week. Yesterday I got the "Kensington News" as soon as it was out, and went at once to a lot of the places advertised. Most of them were taken by the time I arrived. However, there was a place in Ossington St., Bayswater, right by Kensington Gardens, two rooms and use of kitchen at 30/- a week. It was already taken, but only for two weeks. The landlady was out, so I went round there again this morning and arranged to take the rooms from June 14th., and paid the first week's rent on the spot to make sure.

JUNE 1919

Thursday, 5th. Nothing of importance to record for the earlier part of this week.

Today is "June 5th., 1919", which Dorothy and I fixed, last Christmas twelve-months, for our wedding day. In the meantime we have been eagerly looking forward to it, sometimes full of hope and confidence, and sometimes with but little hope for the fulfilment of our dreams so soon. Fate has been kind to us on the whole, in not placing any insurmountable difficulties in our way, though circumstances have not permitted us to keep to the exact day.

Packed up all my things today. Will leave my box of belongings here at Mrs. Stannon's till we come back from Scotland.

Friday, 6th. My N.M.E. leave pass for continuation at the school till October came through today. Went in to town this afternoon and bought a silver watch on a gold bracelet for a wedding present for Dorothy.

Got the 9.35p.m. train for Glasgow. It was an extra train put on because the ordinary one at 9.25p.m. was full up.

Saturday, 7th. Arrived at the station at Glasgow about eight o'clock. Dorothy was there to meet me, and we went up to Campbells' for breakfast.

Grand Hotel and Charing Cross - Glasgow

Grand Hotel and Charing Cross - Glasgow

After that our proclamation of banns was made at Blythswood Church, which is in the parish of Mr. Campbell's residence. Then he and I went down town to see to the legal parts of the programme. I phoned through to the Tullichewan Hotel at Balloch to enquire about accommodation. They were full up, but said we could easily get a room in a private house. Then we went to the Registrar's office, filled in the necessary forms, and obtained the marriage schedule.

It was quarter to one when we got back to the house. Dorothy was dressed in a nice blue dress trimmed with black. Annie was her bridesmaid, and a Rev. Maclaren acted as Best Man. Besides Mr. Campbell, the others present were Mrs. Campbell, a friend but no relation.

Then began the ceremony. It was brief and solemn, and in a few minutes Dorothy and I were pronounced man and wife.

Congratulations were heaped upon us. A light lunch was provided, and then we all came down to the station. The Balloch train was crowded with week-enders, and, as we got aboard, the others surprised us with a shower of confetti. We were covered with it, and so were most of the other passengers in the compartment. The train did not wait more than a minute or two, and soon we left Glasgow, followed by expressions of good wishes from those who had befriended us.

It was about three o'clock when we arrived at Balloch, a pretty little village at the foot of Loch Lomond. Miss Torrance, of the Tullichewan Hotel, had already arranged for us to have a room at the local policeman's house. When Dorothy opened her box and lifted out a coat, a shower of confetti fell from it all over the floor. The sleeves of my travel coat were also stuffed full of it, as were other articles of clothing. Such pranks!

After "high tea" at the hotel, we decided to go to Alexandria to the cinema, as it had begun to rain, and there was no other way of filling in the time. We had to wait a good while at the station, which was crowded with people, because the train was considerably late. At Alexandria we found the cinema, which is the only wet-weather place of amusement about this part of the world. Afterwards, the rain had ceased, so we walked back to Balloch. It was pleasant walking, and the twilight was deepening into dusk when we arrived, the "end of a perfect day".

And so we have reached the long-looked-for goal of our inspirations at last, after many difficulties, and disappointments, and hopes raised and shattered again. There will be many more difficulties to face in the future, but we shall meet them bravely and confidently, and battle through together. Life can be very happy and pleasant for those who really want to enjoy it. And Fate has been very kind to Dorrie and I, in showering immeasurable happiness upon us.

Sunday, 8th. This morning we hired a boat and rowed down the Leven and out on to the loch. It was pleasant exercise, but rather windy out in the open. In the distance grey mountains could be seen vaguely through the misty air, hemming in the water on all sides.

After lunch we went for a stroll through the park, which contains many pretty little spots. Pink rhododendrons bloomed gaily along the walks. The old Balloch Castle is situated in these grounds, and is at present used as Tea Rooms for visitors. We rambled idly through the park, and back to the hotel for tea, after which, as it was then raining hard, we took the train over to Alexandria, and went to the Parish Church. By that time it had ceased raining, but was blowing with great force, almost enough to carry one off one's feet.

The service over, we walked back to Balloch as the weather had taken up. After supper it turned out a beautiful evening, so we went for a walk out along the road through the village.

Monday, 9th. Sent a cable home saying we were married on the seventh. This morning we went for a walk in Balloch Park. The weather was very uncertain, and once we had to shelter in a small hut from the rain. In the afternoon we followed the footpath along the Leven to beyond Alexandria. While returning, a heavy downpour of rain came on. Fortunately there was near at hand a culvert under the railway line, under which we were able to take shelter.

This evening the weather again cleared up beautifully, enabling us to go for a pleasant row out on the loch.

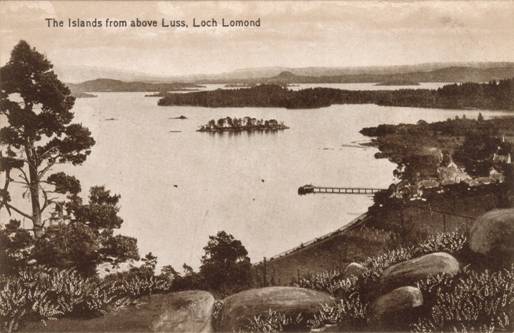

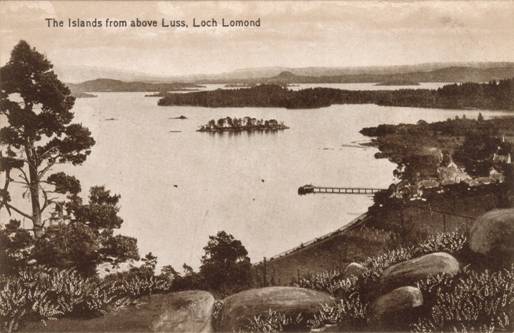

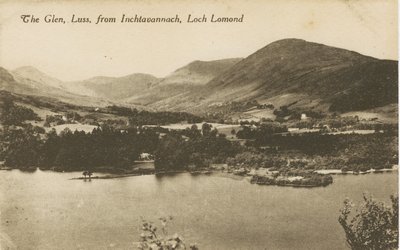

Tuesday, 10th. After a hurried breakfast, we just managed to catch the early train down to the pier, where we got aboard a paddle-wheel steamer for the tour of Loch Lomond. A rather cold wind was blowing, otherwise the day was faultless. Going from Balloch to Balmaha, we passed a line of thickly wooded islands which looked as though they had once formed a continuous spur coming down from the mountain at the back of Belmaha. The village consisted of only a few houses scattered about a wooded headland. From there to Luss, across the loch, we passed many more islands, some flat and bare-looking, some hilly and thickly wooded, and others consisting of mounds of solid rock, besides some pretty little rocky islets crowned with trees and shrubs.

Leaving Luss, we crossed the loch again to Rowardennan, a tiny tourist village, from which the ground rises in long gradual slopes to the dominating height of Ben Lomond. The loch was now becoming much narrower, and hemmed in on all sides by majestic rocky mountains. Tarbet, on the other side, was the next stopping-place. This little village is prettily situated at the foot of high mountains covered with woods. From there we went across to Inversnaid, which apparently consisted of only a hotel. A small stream came splashing down the rocky wooded hillside, and, tumbling over a large rock, formed a pretty cascade, called the Inversnaid Falls, before emptying its gurgling water into the loch. Densely wooded heights rose up precipitously from the water's edge all about Inversnaid. Just opposite, great mountains rose up rocky and bare, and a tiny stream, like a ragged thread of silver, came down the steep rough slopes in a crooked white line against a sombre setting, now leaping forth in a miniature waterfall, now hiding from view behind a projecting rock, and eventually disappearing into a rugged ravine near the foot of the mountain.

Leaving Inversnaid, we headed for the top of the loch. It was quite narrow now, and the steep lofty mountains towering up on either side provided a scene of noble grandeur not easy to forget. Several specks of snow could be seen in the high rocky recesses. One of these, gleaming white on the side of a distant mountain away beyond the head of the loch, was visible from near Balloch, and we had been wondering what it was.

It was about twelve o'clock when we arrived at Ardlui, a town of two houses situated at the head of Loch Lomond. One of the two houses was the hotel. Lunch not being ready, Dorrie and I strolled out along a pretty road lying at the foot of a high mountain with wooded slopes. Coming to a sweet little brook splashing over a rocky bed in the middle of a wood, we followed it down some distance to where it flowed into a larger sheet of water, which I think connects Loch Lomond with Loch Katrine. Everything seemed so calm and peaceful in that sweet wild wood that we were loath to come away.

Back to the hotel for lunch, and then we left Ardlui about half-past one on the return trip. At Inversnaid we went ashore and climbed up around the beautiful falls, over moss-grown and water-worn rocks. It was a charming spot. Dense forests covered the slopes, and the delightful stream came splashing and bubbling along its rocky way. We climbed up around the main cascade and followed its course up through the forest, frequently crossing on the numerous boulders around which the water splashed playfully. Stopping for a rest, we lay down on a flat rock, and, lulled by the soft murmuring of the stream, soon fell asleep.

Awaking some time later, we came back to the hotel for tea. Several coaches crowded full of American soldiers arrived from the Trossacks. They were doing the round tour of the lakes from Callander.

We caught the next boat back from Inversnaid, leaving there about twenty to five. A cold wind was blowing, but the lack of warmth was far more than compensated for by the beauty of the trip. Arrived back at Balloch about half-past six, feeling fit for a hearty supper, after which we strolled out along the road that runs around by the side of the loch. We decided to go on a sketching trip to Luss or Tarbet tomorrow.

Wednesday, 11th. It was raining hard when we got up this morning, so the sketching trip was declared off. After breakfast the weather took up a little, and we walked out along the "loch-side" road. Presumably this is the road to Luss, Tarbet, and Ardlui. Some distance out it ran close down by the water, and from there one had a pleasant view of the loch with Ben Lomond in the background and Beinn Dubh a little to the right. In the afternoon the weather cleared up nicely so we went out there again, and I took a sketchbook and paints and made a rough sketch, with Dorothy standing just at the water's edge. The loch was rather misty, however, and most of the contour of Ben Lomond was obscured.

Thursday, 12th. This morning the weather looked quite promising, so we went down to Balloch pier and caught the early steamer. Bought a book of views and some postcards and a map of the loch, which latter enabled us to pick out by name all the places of interest that we passed. From the names on the map it is evident that "Inch" means Island, and that "Beinn" or "Ben" means Mountain.

First we passed Inchmurrin, a long island thickly covered with trees, then Creinch and Torrinch, the latter looking very pretty with its mixture of light and dark foliage. Our course lay between Clairinch and the beautiful wooded height of Inchcailloch with its steep rocky sides, separated by a small channel from the mainland at Balmaha, which was our first stopping place. Leaving there we passed Inchfad, which is a long low flat island almost bare of trees. Some distance over to the right, Strathcashell Point, a thickly wooded tongue of land, jutted out into the loch. On the left were Bucinch, a round wooded knob, and the rocky islet of Geardach. Farther south were Inchcrum and behind it Inchmoan, only partly visible. These islands all looked very pretty with their forests and hills, and channels of water between. Over to the right appeared Inchlonaig, rocky and round-topped, with the mountains rising majestically behind it.

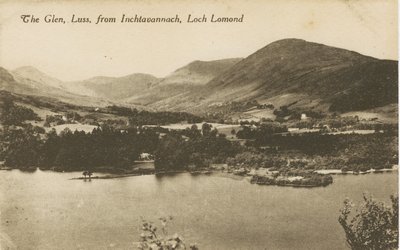

Approaching the western shore we passed the beautiful twin islands of Inchtavannach and Inchconnachan, all covered with dense vegetation, small groups of dark pines enhancing the charm of the lighter green foliage. A high forest-clad hill reared itself up on Inchtavannach. We decided to hire a boat at Luss and row out there. Rugged mountains and beautiful wooded valleys were ranged along the western shore, Mid Hill and Beinn Dubh, the two grandest heights, towering proudly above the village of Luss, which reposed snugly at the water's edge at the mouth of a wide and beautiful valley called Glen Luss.

Nearing Luss, we came past the pretty little islet of Fraoch Eilean, a jumbled heap of rocks crowned with trees and coarse scrub. Close to it were several tiny rocky islets. Arriving at the wharf, we went ashore and walked up through the village, which consists of a single street, along either side of which are pretty stone cottages with walls over-grown with red, yellow, and pink roses, and blue climbing peas. Their fronts were also adorned with patches of pansies. It seemed such a sweet little place, so small and quiet and peaceful. Rain began to fall, and we went up to the hotel intending to have some lunch while waiting for the shower to pass over. However, we found the hotel closed. By this time the rain had developed into a thunderstorm, so we waited under the shelter of the hotel porch until it slackened off a little.

Then we went down to the wharf, hunted up the boatman, and hired a boat. Rowed out past Fraoch Eilean, going between it and the adjacent rocks. We were making towards the channel between Inchconnachan and Inchtavannach when another thunderstorm rolled up, much heavier than before. Heading towards a small beach on Inchtavannach, I rowed strenuously, hoping to get there before the storm came at its worst. But in a few minutes it had swept upon us. The rain came down in torrents, accompanied by a lot of thunder and lightning. Dorothy sat huddled in the stern with her macintosh drawn close about her and umbrella pulled down over her head, looking out occasionally to see that we were going in the right direction. Fortunately the wind and waves were not too violent, otherwise it might have been difficult to manage the boat at all.

The worst of the storm had passed before we came to the rocky beach we were heading for. Landing there, we moored the boat to a large rock and sheltered under some trees for a little while, until the rain slackened off somewhat. Our coats had let the water through in places, but had kept us fairly dry.

We strolled up on the island, which is covered with a thick forest, dense undergrowth, and bracken. The rain had now practically ceased, so we decided to climb up to the top of the hill. Between the trees on the steep slopes the bracken and small shrubs grew in dense profusion, and the thick moss made the ground like a soft spongy carpet. All the undergrowth was saturated from the rain, and in a very short time out feet were wet through and our clothes soaking up to the knees.

Arriving at the summit, we were well rewarded for our trouble with some magnificent views of the loch and the mountains and islands. Ben Lomond, dark and lowering, was partly shrouded in mist. Beinn Dubh rose grandly to a lofty height above Luss. From our point of vantage we were able to look down on Inchconnachan, beautiful with its sombre pines and lighter foliage, and its small hills. Beyond it the other islands extended in a broad ragged line across the loch towards Balmaha, except the dark mass of Inchlonaig more to northward, and the sweet little islet of Fraoch Eilean looking something like a tiny atoll.

Below us the thickly wooded slopes fell away steeply to the water's edge. The whole panorama was very beautiful and very grand, and inspired one with a love and admiration for Nature in her fresh unspoiled grandeur. Reluctantly we left the hilltop and descended by the steeper slope straight down to where we had left the boat. The hillside here was beautiful with different kinds of ferns, and a variety of shrubs and trees. We strolled around the eastern side of the island next to Inchconnachon, and came to a pretty little sheltered bay in the channel. A couple of small boats moored there were the only sign we saw of any human encroachment within the domain of this sweet wild wilderness.

Going back to the boat, we pushed off, and Dorothy took the oars for awhile. The rain had now ceased entirely. We rowed up the channel between the two islands, and the scenery seemed to become more charming from every different point of view. Coming to what looked like a dead-end, we were uncertain as to whether we were really in the channel or only in a deep inlet, so we turned about and rowed out again. There was now no time for further exploration. We headed for Luss, and, though the water was rather choppy, arrived there in good time, about two o'clock. The inclemency of the weather had rendered any sketching impossible.

At one of the cottages in the village we got some lunch, and were just in time to catch the steamer back to Balloch. Having changed into some dry clothing, we spent the evening in the hotel parlour with Naval-Lieut. Scarr and his wife, who were married the same day as we were. Packed up our things tonight, ready for departure in the morning.

It has been such a happy holiday here that the prospect of leaving is not a welcome one. Loch Lomond is so grand and wild and free from the trammels of civilization, what one wants to stay here always. We have had a jolly honeymoon, in spite of the weather.

Friday, 13th. We left Balloch by the nine o'clock train. At Glasgow we were met by Mr. and Mrs. Campbell and Mrs. Brown. We all proceeded to the pier and went aboard the "Lord of the Isles" steamer for the day cruise down the Clyde estuary to Tignabruaich.

The boat got under way at eleven o'clock, and we came down past the great ship-building yards with their continual rattling of hammers and clanking of steel. We passed ships of all sorts and sizes, in various degrees of completion. Some were merely skeleton frameworks, others launched and finishing. At one place there was a warship in course of construction, and some small submarines.

Getting away from the city, the stream ran through fresh green country and soon began widening out into the estuary. The day was fine, and, save for a rather cold wind, was very pleasant. Mr. Campbell acted as guide, and told us all about the places along the route.

On the left we came to Greinock and Gourock, two adjoining towns. We could see the road from Gourock to the Clock, which was the scene of Harry Lauder's "Roamin' in the gloamin' on the bonnie banks of Clyde".

Lock Long appeared on the right. Away beyond it Ben Lomond could be easily recognised by its distinctive shape. Beautiful rugged mountains surrounded Loch Long and another deep inlet a little farther down. At the point of the peninsula between these two lochs a small town lay spread out along the water's edge. Just across the inlet, on the next point farther down, the pretty town of Dunoon appeared among the trees.

The wind became strong and cold. Green wooded hills rose up on the left, and rocky mountains away to the right. Our next stop was Rothesay, a fair-sized town. Thereafter the estuary became narrower till we came to the Kyles of Bute, a narrow strait with rocky hills and mountains on either side. The scenery about here was beautiful, the great rugged masses of rock forming a huge natural gateway for the waters of the Clyde.

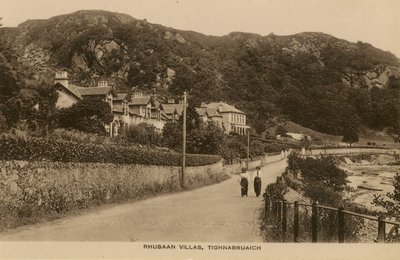

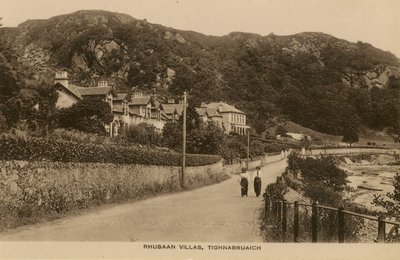

A little farther on we came to Tignabruaich, a sweet little village tucked snugly under two great knobs of rock surrounded by forests. It was twenty past three when we arrived there, and, as the boat was staying for twenty minutes, we went ashore for a little while.

It was not quite so cold returning, and some of the mountain mists had cleared away, allowing us some beautiful views of bays and distant rocky ranges. A tragic incident dimmed the pleasure of the return trip. A child was found to be missing, and though the vessel was searched from stem to stern, no trace of it could be found anywhere. It may have fallen overboard, and it may have wandered ashore amongst the other passengers at Rothesay. The poor mother was distracted with grief. When we got back to Rothesay, enquiries were made there, but nothing was known of the missing child, and it was feared the poor little mite had fallen overboard near the paddle wheel, where it would be carried straight under and might easily escape the notice of passengers.

We arrived back at Glasgow after eight o'clock, and went up to the Campbell's for supper, after which we said goodbye to our friends and left by the 9.45 p.m. train for London.

Saturday, 14th. Arrived at Euston about half-past seven. Breakfasted at a restaurant, and then went out to Bayswater, to our temporary home. Our quarters are modest enough, but comfortable. Left Dorothy shopping at Whitely's, and went over to Mrs. Staddon's at Earl's Court for my belongings. There was a letter for me there from Viv, written from Sutton Veny last Monday. He had got across to England, and was to come on leave yesterday. Sent him a telegram care of Mrs. Morgan, giving our new address.

This evening we went for a walk through Kensington Gardens to the Serpentine. Everything was calm and peaceful, the quiet water with its many reflections, the trees with their thick green foliage, and the broad green carpet of grass. People lounged on the chairs enjoying the peacefulness of this retreat from the busy city. Others, in boats, rowed up and down the pleasant waters of the Serpentine. Twilight came on, and folded everything in its soft embrace. It was like a haven of rest for the weary toilers through the trials and storms of life.

Saturday, 21st. We had a visit from Viv on Monday. He had been staying at Mrs. Morgan's and he said that Mrs. Caborn has another little daughter. Viv has hay fever rather badly. He has since gone to Ireland to see Mrs. Hyndman.

On Wednesday I went out to Mrs. Morgan's to collect the rest of my belongings stored there. Packed them all up in my valise and red box, but could not get a taxi that night to fetch them to the station. While there Mrs. Morgan tackled me for my recent neglect of her, and accused me of "base ingratitude" for all that she had done for me. She said a great many unkind things, which only made me feel less than ever inclined to renew the friendship.

Next day I went out again for my things. Mrs. Morgan was then much calmer, and even agreed that there had been a "mutual misunderstanding" between us. So we parted friends, but it will be practically impossible to maintain our former friendly relations after some of the things she has said. It seems a pity, but such is life.

My valise and box were a weighty problem. Got them to the station in a taxi, and then there was the task of juggling them about at Acton Town and Sloane Square, where I had to change. Got them in a taxi from Queen's Road station to the house, and what a blessed relief it was to have done with them at last. Its no joke acting as one's own batman on such occasions.

This evening Dorrie and I went to the Coronet Cinema Palace at Notting Hill Gate. Besides the films, they had a fine orchestra, and rendered a beautiful selection from "Faust".

Saturday, 28th. On Tuesday news came that the Germans had accepted the Peace Terms. They had haggled over it to the last, and had only signified their acceptance two and a half hours before the expiry of the time limit.

This morning we learned that the Treaty was to be signed this afternoon at three o'clock. About four o'clock special editions of the evening papers announced in the Stop-press Column that Peace was signed. Some little time later the firing of guns signalled the completion of the ceremony.

After tea Dorothy and I went in to the city to see the rejoicing. Trafalgar Square was crowded with people and gay with bunting. All vehicle traffic had stopped, and many flag sellers were busy at the corners. Lots of young girls amused themselves with "ticklers" and enjoyed the fun immensely.  The fountains were flowing, and Nelson's Column was brightened with flags. The Joy Loan Thermometer indicated that already seventeen million pounds had been received today. Some of the people were firing crackers and tame bombs, the latter making quite a loud explosion. The people were all in happy mood, with the realization that actual definite Peace had come. The humour of the crowds seemed to breathe the spirit of "Peace on Earth, Goodwill among men".

The fountains were flowing, and Nelson's Column was brightened with flags. The Joy Loan Thermometer indicated that already seventeen million pounds had been received today. Some of the people were firing crackers and tame bombs, the latter making quite a loud explosion. The people were all in happy mood, with the realization that actual definite Peace had come. The humour of the crowds seemed to breathe the spirit of "Peace on Earth, Goodwill among men".

We wormed our way around the square and went up to Buckingham Palace, where people were already collecting. From there we walked up to Hyde Park corner. Numerous processions of Boy Scouts came past making quaint music with their bugles and drums, and looking picturesque with their various uniforms and banners.

While watching a long procession of the Scouts, a man in "civvies" came up to me, and I was very surprised to find it was Arthur Hopper. We stayed for some time talking about old times and friends. Then Dorrie and I went back to Buckingham Palace and waited there in the crowds. They were a good-humoured lot, and were determined that the King should come out. They sang "We want King George", to the tune of clock-chimes. They shouted, chimed, sang songs, blew whistles, cheered, and clapped in turn for the space of an hour.

Then the door on the centre balcony opened and the king stepped out, followed by the queen, the three princes and Princess Mary. Thundering cheers greeted their appearance, and immediately the crowd began to sing "God save the King", the strains welling up in one vast volume of sound. The king was dressed in naval uniform, and the three princes in khaki.

The cheering and singing continued for some time, and a band in the courtyard played many popular tunes. At the end of each piece the cheering was resumed with vigour, and acknowledged each time by the king with a salute. After some time the king gave a short address. The first few words were drowned in the general hubbub, but then a profound silence fell on the crowd and I heard the rest. ".....demonstration of loyalty on your part. We are deeply touched, and thank you for your kindness on our behalf." This was followed by more thundering cheers.

The twilight was now deepening into dusk. The people sang "God bless the Prince of Wales" several times, and began to call for a speech from the prince, but he did not come forward. Darkness set in, and some of the crowd began to move. Dorrie and I had just started to go, when the Prince of Wales also gave a short address, but we were too far away to hear. A little while after, the lights were switched on in the room behind the balcony, and the royal group appeared silhouetted against the windows. There followed a loud and prolonged burst of cheering, to which the king and prince both saluted, and then they went inside and the crowd dispersed.

The searchlight display was now in full swing, but the night was not dark enough to make it really effective. We went down the Mall to Trafalgar Square, which was now densely packed with people. The Loan total for today as indicated on Nelson's column had risen to fifty million pounds.

It took us a long time to get across the square and into Villiers St. Then there was an awful crush in front of Charing Cross tube station. We were packed tight in the middle of it for about twenty minutes, and were then carried bodily through the gates. At last we got in a train, and arrived home just before midnight.

Sunday, 29th. Got busy today writing up some of my arrears of correspondence to Australia.

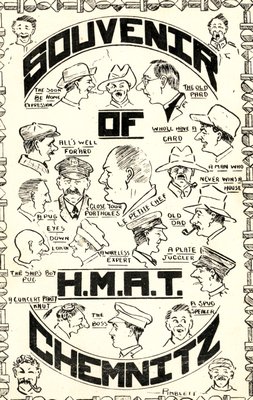

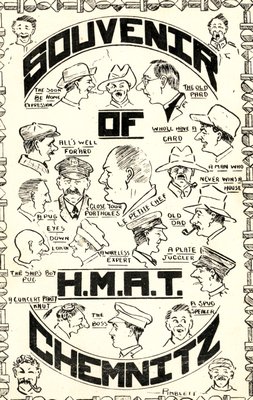

Monday, 30th. Viv dropped in today for lunch. He is leaving England on Saturday on the "Chemnitz", a converted German cargo boat, and is in charge of the draft. Gave him one of my brass shell-cases, as he hasn't got one, and commissioned him to get a small cottage for me when he arrives home.

JULY 1919

Saturday, 5th. Got my correspondence to Australia all written up by Wednesday. Dorothy became unwell on Tuesday, and on Thursday she went to see the doctor. He said she had rheumatism, and gave her some liniment and other stuff. She was not at all well last night, and kept to her bed most of today. Wrote to Mum and Dad last night and told them I might be home about the end of September.

Saturday, 12th. Dorothy was still very ill on Sunday, and kept to bed all day, but was almost quite well again by Tuesday evening. On Tuesday I had a letter from Viv saying he was leaving on Monday (yesterday) as the "Chemnitz" was delayed a couple of days. Also had a letter from Aunt Lydia renewing her invitation to "The Hills" and asking me to bring Dorothy.

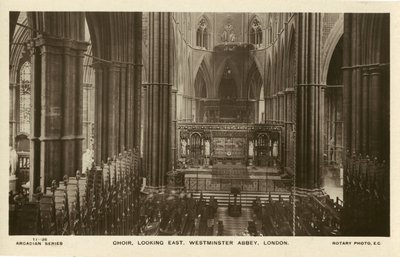

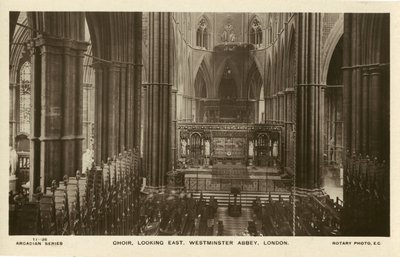

This afternoon Dorothy and I with Mrs. Bach went in to Westminster Abbey. It is a very fine old building, full of interest and beauty in every nook and corner. There was some beautiful statuary near the entrance, including a handsome monument to William Pitt. That part of the Abbey built by Henry 7th. appealed to me as the most beautiful, with its fine ornamental ceilings and walls. From some of the small chapels one could have fine views across the interior, through walls of open stonework. The tombs of the various English monarchs are intensely interesting from a historical point of view. Some of these are so old that the stonework is crumbling away.

Though not so grand as some of the continental cathedrals, Westminster Abbey is infinitely more interesting, and has such a wealth of beautiful detail, that brings it far above them in importance.

We had tea at Slater's in Piccadilly, and then finished up the day at one of those vulgar amusement places where they have a shooting gallery, fortune-telling machines, other machines that provide a miniature cinema show, and various other interesting and amusing ways of accumulating pence.

Saturday, 19th. On Sunday Dorrie and I went out to Kew Gardens for the afternoon. It is always so nice and pleasant out there, and bears a different aspect every few weeks. When first I came out, the trees were all bursting forth in their full spring beauty. Next time I came the grounds glowed with a golden glory of daffodils. At a later visit they were charmingly bright with bluebells. At another phase in the summer's progress the gorgeous warm-coloured azaleas held triumphant sway, and a little later the pleasant parks were brilliant with rhododendrons. And now the roses were becoming the chief attraction, and endowing the gardens with their beauty.

On Tuesday, Beat Smith came to London. Dorrie and I went in to Waterloo to meet her. They two went on to Mansion House, to Beat's warehouse, where she has to buy for her firm. In the afternoon I went in again and met them and we had tea at the Strand Corner House. After that we went to Waterloo and saw Beat off. She had given Dorothy a lovely white bedspread for a wedding present for us.

Dorrie and I went rowing on the Serpentine on Wednesday evening, and again on Thursday. We had to line up in a queue for the boats, but the waiting was amply rewarded when our turn came. The evenings were warm, and it was a joy to be on the water, especially in such beautiful surroundings.

Yesterday I took a pen drawing and some advertisement designs in to Byron Studios. On several previous occasions I had tried to dispose of some of my work at various places, but without avail. This time the pen drawing was rejected, but the other designs were considered quite good, and the manager took my address. The firm has a staff of artists to do the work that comes in, but at times they get more work than they can manage, and then it has to be sent out.

While in town I went through St. Paul's cathedral again. One appreciates its beauty and grandeur more and more at each visit. It is much more magnificent than the continental cathedrals, although not so beautiful in design and architectural structure. Climbed up to the Whispering Gallery, which is around the inside of the great dome. This gallery derives its name from the fact that a whisper can be heard from the opposite side of the dome. The sound travels around the wall, and seems as though it comes from someone inside the wall a few yards to one side. A man on duty there gave us a short history and some interesting facts about the building, all told in a whisper from the opposite side of the dome. It seemed incredible.

Went up higher still to the Stone Gallery, which runs around the dome on the outside. From here one commanded some fine views over London, with the broad white Thames winding through it, and the Hempstead Hills in the distance.

Cheapside, Ludgate Hill, and thereabouts was gaily decorated with flags and bunting of all sorts and sizes for the great Peace Celebrations. It was like a moving sea of colour. In the afternoon I was over in Kensington, and High Street was almost smothered with banners. The preparations were still going on, workmen being busily engaged in adding the finishing touches.

After tea, Mrs. Bach and Dorrie and I went in to town to see the decorations. Selfridge's was got up very nicely, with white statuary along either side of the street. Coloured bunting, flags, coats of arms, and all sorts of decorations were in abundance everywhere. Mrs. Bach was inclined to criticize the lack of artistic taste displayed, but I was deeply touched by the human side of all this gay show. It marked the end of the years of cruel warfare and dreary hardships. It meant a lot to me. Those gaudy cloths and things expressed the joyous relief and thankfulness of thousands and millions of my fellow beings that the war is over and Peace is signed. All the people were rejoicing with me, and it touched the deepest chords of emotion in my heart. None but soldiers know, or even guess, what war is.

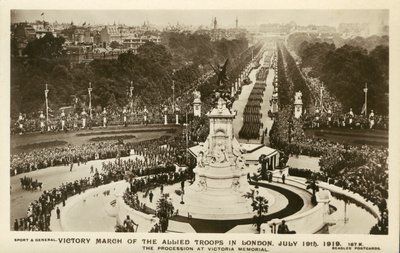

We went down along Bond Street, and then up to Buckingham Palace through an avenue of white pillars with standards and laurel wreaths. These pillars were also adorned with all the different regimental badges of the British Army, and upon a number of them were inscribed the names of all the battles fought by the British Army in the war. In front of the Victoria Memorial stood a newly erected covered dais for the king to stand on to take the salute in the March Past.

We went down the Mall, which was also made an avenue of white pillars with standards, laurel wreaths, and regimental badges. From Trafalgar Square we went along Whitehall which displayed a wealth of colour everywhere. The Cenotaph memorial to "Our Glorious Dead" was a plain stone monument with a laurel wreath at the top. Its modesty and lack of decorative effect were, I thought, befitting to the purpose for which it was erected. It expressed a silent homage from millions of hearts to those who have gone to the Great Beyond, whose numbers include our dear old Bert.

Many of the decorations were still being fitted up on the buildings. There was no very great display of artistic merit or originality, but every street and square and alley spoke of deep human feeling and thankfulness for peace. We caught a train home from Westminster, more or less tired after so much walking about.

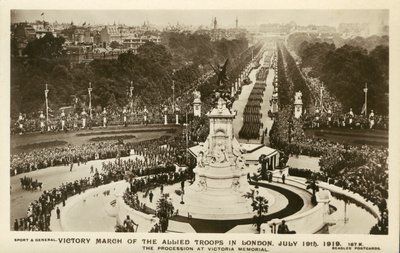

This morning dawned the great day of the Peace celebrations. After a hurried breakfast Dorrie and I got round to Victoria with some difficulty, as the trains were crowded. We had decided to go to Vauxhall Bridge Road to see the procession, as it seemed less likely to be overcrowded than the other parts of the route. Crowds of people were packed densely outside Victoria station, but we managed to get through and down along Vauxhall Bridge Road. Crowds of people lined the road. Every window was occupied. Men and women stood on boxes, chairs, and improvised seats along the pavements. Doorsteps were made full use of. Walls, roofs, fences, and all available points of vantage were occupied by eager waiting people. A numerous force of police were kept busy all along the route managing the crowds, and St. John's Ambulance men had plenty to do looking after fainting women. We found a good position on the pavement, the people in front being only four or five deep at this spot, and an iron fence behind being handy for Dorothy to get up on to obtain a better view.

We did not have very long to wait. At about twenty minutes to eleven the procession began to come past, headed by Americans with General Pershing leading. I was a little disappointed that the Americans, who entered the war so late, were given first place. I had rather seen the French or Belgians lead the march, and I think most of the people felt the same. However, Pershing and his men were greeted with rousing enthusiastic cheers. The Yanks looked uncomfortable in steel helmets. Their colours were massed, and made a fine spectacle, some of them being very old and tattered.

Next came the Belgians, all wearing flowers in their buttonholes. The cheering increased greatly in volume as the representatives of that brave little country marched past. After them came a small contingent of Chinese troops, led by General Tang. They were remarkably stolid and unemotional, with not the least flicker of a smile on their faces. I could not help wondering what their thoughts and feelings might be.

The French contingents followed, led by our great hero, Marshal Foch. Deafening thunders of applause greeted his approach. I was glad of the opportunity of seeing Foch, who is beyond doubt the greatest military leader of the war. But for his skill it is very unlikely that the war could have been finished so soon. There were various French units represented, some in khaki, but most of them wearing the familiar light blue, also a number of French blue-jackets, and French African troops, Algerians and Moroccans.

Next came a contingent of Greeks, followed by a long column of Italians, the latter looking very smart in their grey uniforms. They were led by General Montouri, whose breast was covered with a host of medals. Then came Poles, in grey, and Portuguese, in khaki, also Romanians and Serbians, a body of Siamese, who were small strange-looking little men somewhat resembling Chinese, also clad in khaki. The Czecho-Slovaks were a tall fine-looking body of men in their blue-grey uniforms and "Glengarry" caps. They marched past with a proud manly bearing. The Japanese were not so stolid as the Chinese, and smiled in amusement at the cheering crowds.

They were the last of the Allied contingents. Russia and Montenegro were not represented, probably because none of their troops were available. It was a fine sight to see the Allied soldiers go by in the March of Victory. It seemed as if all the world were arrayed in anger and indignation against Germany. It was all very stirring, and like what one reads about old-time triumphal marches, each group carrying their flags and banners, and the cheering from the crowds along the way being at times almost deafening.

Then came the British Navy, Sir David Beatty at its head. He could be easily recognised from the photos one often sees in the periodicals. A number of naval brass bands were included, and contingents from the various battle squadrons, also Royal Fleet Reserve, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, a number of "Wrens" led by Dame Furse, Naval nurses, and Sea Scouts. There were a large body of men of the Mercantile Marine, many of them in civil clothing, and, last of the navy, the Seamen's Union, with their banners.

Last of the great march came the British Army. Sir Douglas King was greeted with loud and enthusiastic cheering, and, by the thunders of acclamation accorded to the Tommies, it could easily be seen where the hearts of the masses of the people lay. Haig was accompanied by many other generals, including Birdwood, who looked as amiable as ever.

Here and there among the troops were various regimental bands, and various lots of massed colours and standards, all bearing laurel wreaths. Units from the Artillery, Horse, Field, and Garrison, came past with several big guns. Then the Royal Engineers, followed by wagons with two pontoons. A contingent of the "Old Contemptibles" were cheered with hearty fervour. Then passed various units from all the Infantry regiments, occupying a long portion of the procession. They were followed by the Tank Corps with four great tanks lumbering behind them, the Trench mortars in motor lorries, a searchlight and an anti-aircraft gun.

Next in the march were the colonial forces, Canadians leading, then the Australians, led by General Monash. I did not see any 24th. Bn. men amongst them. They were only a small party, about one hundred altogether. New Zealanders followed, then South Africans. After them came a number of women of the Women's Forage Corps and the Women's Legion, followed by nursing matrons, sisters, and V.A.D's. Even the Military Police were represented. Last in the march were the Royal Air Force, including a body of women of the W.A.A.F.

The whole procession took just on two hours to pass, and must have been several miles long. When the last of them had gone by we started for home, but it was hopeless to try to get into Victoria station. All the streets in the immediate vicinity of the march route were strewn with discarded newspapers, which gave them a strange appearance. Many people had brought lunch baskets with them, and were sitting on the doorsteps all along the streets, enjoying a light repast. It was a strange sight for London in the West-End.

We walked to Knightsbridge, but the tube station there was also inaccessible. Dorothy was by this time very tired after the morning's exertions. We went into Hyde Park, where crowds were already gathering for the afternoon's entertainments. Managed with difficulty to get into a ferry-boat, a large rowing boat, going across the Serpentine, and thus got over to Lancaster Gate station, from where we were able to get a train (to) Queen's Road, arriving at the house about two o'clock, absolutely tired out.

We had some lunch and a short rest, then out again about three o'clock with Mrs. Bach. Hyde Park was now quite crowded. Country dances and folk dancing were going on for the entertainment of the people, and there was also an open-air Shakespearian play comprising fairy scenes from "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

Not long after we arrived there the king, queen, Prince Albert, and Princess Mary drove up in a carriage and came along the road by the Serpentine. Their carriage was thronged by crowds of eager people, and had to come to a standstill. They stayed there some little while, and we got a good view by standing on a chair. Then they turned and drove back to the main road through Hyde Park.

We stayed for some time watching the fairy scenes from a "Midsummer's Night Dream." There were King Oberon in flowing robes, Puck, the little jesters, and a number of fairies prettily dressed in grey gauzy stuff, one of them, presumably the fairy queen, being in pink. Their actions and dancing were delightfully graceful. Unfortunately we could not get close enough to hear everything.

Our intention had been to stay and hear the choir of ten thousand voices, but a light rain set in about six o'clock, so we left and came home.

At nine o'clock, feeling rested and refreshed, Dorrie and I ventured forth again this time to see the great fireworks display. Mrs. Bach did not feel quite equal to it. The trains were terribly crowded, but we managed to squeeze on to one, and got to Marble Arch about ten. As we were crossing the road several loud reports burst upon the air, and then the sky over the park was filled with gorgeous showers of lights of all colours, which streamed downward leaving beautiful trails of white smoke. It was the beginning of the fireworks display. We hurried over to the park, where large crowds of people had gathered. Climbing over fences and barriers, we eventually got round to a suitable position, as Dorothy, being small, could not see easily over the heads of people in front.

I had never before seen a fireworks display on any grand scale, and this one left me spellbound at the wonder and beauty of it. There were hundreds of rockets streaming up into the sky leaving long trails of sparks, and then bursting into showers of bright coloured lights. There were some wonderful colours of mauve, gold, purple, blue, heliotrope, and white. The red and green stars were brighter, but not so beautiful. Some of the star showers burst at a tremendous height, and some were scintillating with a wonderful and beautiful effect, while others lit up the whole park with their brilliance.

About every five minutes there would be a number of loud reports like trench mortars, followed by explosions in the sky, and a different display would appear each time. Several times they burst into great masses of red or green lights. Other displays took the form of amazing showers of dazzling silver lights which would turn to gold, then to blue, mauve, heliotrope, or green, and fall slowly and die out, leaving the sky full of a mass of dull gold sparks. Other "trench mortars" would burst at a high altitude and send out long trails of spark showers in all directions. These would fall, and for a time look like some strange fiery plants growing out of the sky and sending graceful branches and tendrils towards the earth.

The sky became full of smoke in great billowing masses and in long white trails, and the continuous lights and rockets glowed with a beautiful effect among the clouds of smoke. There were countless numbers of rockets and flares of every conceivable variety and colour. There were parachute flares and ordinary signal flares, and strings of red, green, or other coloured lights hanging in crescents from parachutes at either end. Many of the rockets sent out showers of different coloured stars which scintillated and sparkled like clusters of moving diamonds.

All this while there was another part of the display going on closer to the ground. There were hosts of brilliant fiery things dashing up in all directions with dense trails of dazzling white sparks, also myriads of queer-looking "wiggly-waggly" things, glowing golden yellow, like hundreds of fiery tadpoles chasing each other in and out, some dashing right out to one side, as though running away from the rest. There were the pip-squeaks, whistling rockets, and great fountains sending up a continuous spray of coloured lights.

The display came to an end about eleven o'clock, after lasting an hour. We walked over to look for the fire-portraits, and found the frames for them with the fusing not fired because it had got wet by the rain. We were able to recognise one of the portraits as that of Lloyd-George, and two of the other frames contained the words, "Peace - thanks to the boys", and "God save our King". Most of these frames, which stood about twenty feet high, were being pulled down by boys and soldiers and sailors, who wanted to get the fusing.

Farther over towards the Serpentine a line of large ground-flares was started going. They blazed fiercely something like German incendiary shells, but with a dazzling white light, making strange lights and shadows among the trees. We stayed there until they were burnt out, and then started for home. Streams of people were now moving through the park towards the gates. The north-eastern sky was covered with a great red reflection, probably from one of the chain of bonfires around London.

Arriving at Lancaster Gate, we found a big crowd of people around the station. It was hopeless to think of getting in. All the busses were packed full, so we had to walk home. Bayswater Road was crowded with pedestrians homeward bound, train or bus or taxi being out of the question. We arrived at the house about midnight, and to finish the day's celebrations I got my Hun flare pistol and fired off about half a dozen flares. The noise brought night-capped heads out of windows all along the street to see what it was.

We were very tired after all the day's excitement. This marks the final closing down of the world-war, and the dawning of the life of peace.

Saturday, 26th. On Monday I went into Hqrs. to arrange about a passage to Australia on a family ship, and found that it is impossible to get away before the middle of August. Went in again on Tuesday and was told that the "Anchises", which will be the last boat to sail in August, was already "full up", but it was arranged that if any of the passengers should be unable to travel, as often happens, we should be put in their place. Failing that, we should have to wait till the first week in September.

However, Dorothy received a notification from Hqrs. yesterday morning saying that accommodation would be reserved for us on the "Anchises", which was due to leave Liverpool for Australia on August 19th. Needless to say, we were delighted at the prospect.

Yesterday afternoon Dorrie and I visited Madame Tussaud's, and found it extremely interesting and instructive. First we went in the Children's Gallery, which contained some very pretty tableaux, including "Babes in the Wood", "Jack the Giant Killer", and "Cinderella". They were prettily arranged, and the wax figures in them were very lifelike and natural. From there we came to the Tableau Hall, in which were some fine historical wax-figure tableaux, "Alfred in the Neatherd's Cottage", "Coronation of Queen Victoria", "King John signing Magna Charta", and "Execution of Mary Queen of Scots", also a number of others.

The main part of the exhibition contained cleverly executed wax figures of the leading statesmen and notable men and women of various periods, all the monarchs of England from the earliest times till the present day, and some of the most famous foreign monarchs. There was a large group of present-day statesmen and rulers of Allied countries, and the chief naval and military commanders. This group included King George, Foch, Beatty, Haig, Lloyd-George and many others.