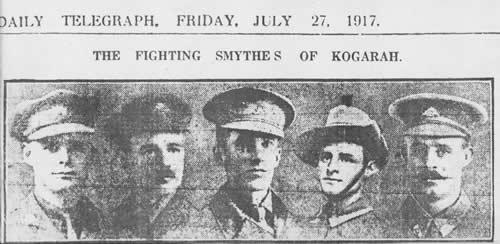

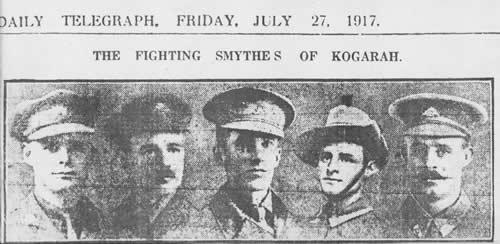

The War Years

Gallipoli

Bert wrote home describing the Landing at Gallipoli on the first day also life at the front, and many of his letters were published in the Jerilderie Herald and in city papers. In spite of Bert's lack of formal education the editor felt "they were descriptive letters... cleverly written too." His unique sense of humour was evident, his style being very different from Percy's.

I was feeling as right as rain until I saw my first sight of the harvest of war. I saw blood oozing from beneath a tarpaulin and a sailor told me there were four dead men under it...killed by shrapnel on the destroyer before they even landed.

When the boats got into 3 ft of water, we all jumped out & waded ashore feeling mighty thankful that we'd got so far...after a short spell we marched off. Hills! They're awful. We simply had to pull ourselves up hand by hand, & to improve matters we had 50 rounds of extra ammunition, three days rations, & some firewood. Presently we got to a plateau with a lovely trench in it that the Turks, with commendable foresight had provided for us.

By the end of April he was injured in the arm and evacuated to the First Southern Central Hospital in England. This was referred to as a "Blighty", an injury serious enough to be sent to England, The Motherland, not immediately home to Australia. It gave the men a chance to see something of another country. On 3rd May he wrote in a very shaky hand,

Dear Mum & Dad & brothers & sisters

I've been wounded in the right shoulder & am progressing finely. Vernie is O.K., saw him just before they took me away. Had been in the firing line 4 days before they got me. On the morning of the fifth day the Tommies releived (sic) us & they got me as we were retiring to the rear for a days rest so now I'm going to have more than a days rest. Its hard work writing & makes me tired, so will you please tell Clytie etc.

We are very comfy here. Nice soft bed and attendants that spoil you

I suppose that you'll see the casualty) lists long before you get this

I've lost every mortal thing I own except the clothes I used to stand in & my great coat. Had four different rifles during the fighting. The beggars never gave us a moments peace the whole time I was there

Love to all from your loving son & brother

Bert

Anxiously the family awaited news from the front. At last they heard from Vern that Bert's wound was only a flesh wound and he would soon be all right, while Vern was comparatively safe at headquarters, fifty yards behind the lines. Although the youngest of the four brothers in the AIF, Vern was the first to get promoted beyond lance corporal, becoming a second lieutenant in May.

Bert’s skill as a sniper stood in the way of promotion. While recuperating, he wrote about his experiences and the Jerilderie Herald published his account in two long articles.

Bert heliographing in Egypt

Among his comments:

We landed in a bad place, and it's just as well. The Turks were expecting us at another place, and had we gone there we would never have got ashore. They had guns and machine guns, splendid trenches, obstacles, and even barbed wire entanglements and mines in the water to welcome us with. Where we actually did land was not very strongly guarded and we sort of surprised them, and we had got ashore and established ourselves before they could bring sufficient troops to prevent us. Once we got ashore it was just a matter of holding on...Finally we got on top of a hill with a pretty good trench in it. The fact that it was a Turkish trench didn't worry our consciences in the least. We just took possession of it and inwardly thanked the Turks for saving us the trouble of digging one... Every few seconds a shell burst, sometimes near us and sometimes a bit off, and they kept our nerves on edge all the time. Shrapnel looks very pretty. The shell bursts up in the air and makes a pretty cloud of white smoke, and when several burst near each other at the same time the effect is very striking. But when the shooting is good it is very nerve racking. The shell can be heard some distance off coming with half a scream and half a hiss, culminating in a deafening report as the charge in the shell explodes, and drives 300 bullets in a steep angle to the ground with great velocity... The Turks will go to any length to gain their ends. Several were shot dressed in the NZ uniform. Some of them were very brave and actually got into our trenches and were giving orders as cool as cucumbers: but they invariably got discovered and paid the penalty. They'd get up and order us to charge, and all sorts of other dodges...A concussion shrapnel landed right in the trench fair opposite us and buried us up to our necks in dirt. I scrambled to my feet to see if I was hurt and was mighty thankful to find I wasn't... Whilst having tea a bit after dark I had to take an officer to a trench he did not know! Only expected to be away 10 minutes so I left haversack, water bottle, rifle and all behind me. While away the enemy suddenly threatened us with a bayonet charge so we all rushed to the front line. I grabbed a rifle - a broken one too - fixed the bayonet and hopped in with them...Later we had to cross over about a hundred yards under fire to reach safety at the rear of a hill so we rushed over. About ten yards from the safety trench I stopped to walk when I got a knock in the shoulder like the kick of a 12-inch gun. I didn't want another, and tumbled into the trench mighty quick. Got the wound dressed and was led back to the rear. I'm hanged if I know where the beggar could have been. He must have been almost under me, and the valley beneath us was full of our own boys. The bullet went in at the back of my armpit and came out near the top of my shoulder in front. Had the good luck to see Vernie near the Ambulance Hospital. He was O.K. and made me a cup of tea and it quite put me in a good humour. I then had to report to the ambulance and they shipped me off to the hospital ship before I knew what was doing. Did not get another chance to see Vernie and haven't heard word since, so I am rather anxious about him... Had a fairly good time on the hospital ship on the way to Alexandria, but got a bad dose of fever of some sort, but I am pretty right now though the fever took a lot of the flesh off me. My wounds are healed externally, but I can't for the life of me lift my arm up sideways yet... We arrived at Southampton, Sunday 16th May. They put us in a lovely hospital train. You ought to see the English scenery. In Spring- well words can't describe it. Lovely green fields fringed in almost every case by either beautiful hedges or trees... We got a great reception at Birmingham. As soon as we got off the platform there was a long line of motors waiting for us, and an enormous crowd and they cheered us all a treat. It was the same all the way to the hospital. Everybody we passed waved to us and gave us a smile of welcome. It was particularly cheerful after being outside of civilisation since we left dear old Australia.

But this hospital takes the bun. Why it's a blooming gaol. The things we mustn't do that we want to do are only exceeded by the things we must do that we don't want to do. Practically all of us have been kept in bed though we are all able to potter round. Lights are out at 8 pm. We all have to get up at 5 o'clock so that the beds can be made, and then we have to get back into bed. There are 44 beds in this ward, which is known as "B4". I asked the nurse if we'd be put in the "after" Ward next week, but she didn't even smile. That's the worst of these nurses. They don't smile enough. They all get about as sober as a captured spy. I've been working overtime making them smile whenever they come near. Drew absolute blanks at first, but things are improving now. Got one of them to look quite happy for 10 secs. It makes me feel quite desperate. Good news! The quack has just been around and he says that I can get up, so when they bring me my gaol suit-coat and trousers of blue fleece lined material- I'll do so. They have all my other clothes so of course I HAVE to stay in bed. The regulations only allow us to wander in certain parts of the grounds so even our liberty outside is curtailed. As for getting out and looking over Birmingham, I believe the nurses would have a seizure if you mentioned it to them.

I haven't had a shave for a month. You ought to see me. I lost everything but what I stood up in when I was shot including my razor etc.

Birmingham was a very old city about a hundred miles north of London. In early times it had been an important market town. Open-air markets were held in the heart of the city in an area known as the Bull Ring*. Upon his discharge Bert was given leave in London before going back to Gallipoli. Bert met one of his signallers, Percy Morgan, who was also wounded. Percy, an Englishman aged 21, was working as a rural labourer in Australia when the war broke out, so he joined AIF. In London he took Bert to meet his family which made Bert feel homesick. Mrs Morgan became a friend to all the Smythe boys and thought she might visit Australia after the war with her son if he was expected to return to his job for another six months. She wrote to Annie "I find with Bert the more you know him the more you like him. I love the way he speaks of you and all family ties."

A letter came to Annie from the girls at North Winton with a bank draught for £100. Their sister Lydia also received the money owed her. It was nine years since their father had died. Percy noted in his diary "There was the money which Pater left to Mum paid at last, though she had never expected to receive it. It will come in handy just now in paying off Schnacker's mortgage on our cottage." To help their parents meet the commitments for the house the boys made allotments out of their pay. Of course Viv also made one to Clytie.

Eric, Ida, Rita, Annie, Ted, Gordon. Koppin Yarratt, Kogarah ca 1915

Eric, Ida, Rita, Annie, Ted, Gordon. Koppin Yarratt, Kogarah ca 1915

As suggested by Percy, they called the house "Koppin Yarratt" or KY for short. In time they found to their dismay that the builder had omitted the dampcourse (a strip of lead used between the brick courses to prevent dampness rising into the walls) as a cost-cutting measure. Apart from that they were very pleased to be in a house that they would own one day, their first. Next door lived Frank Jones who was to be their neighbour for many years.

One day while at Ramsgate Beach Annie said "Why didn't we come here before instead of going to Jerilderie?"

Bert’s Letter

After a period of convalescing in "Blighty" (England), Bert was back to the fighting and after a couple of months he was sent, sick, to the nearby island of Lemnos and again to England. While in England for the second time, Bert again wrote of his experiences in the trenches and again the Jerilderie Herald published them. He had applied to become an instructor of signalling in England. He saw a “mackintosh”, a rubbered silk coat, light and showerproof, which Mrs Morgan had bought for her son. Bert bought one for his brother Percy, but the parcel did not arrive before the troops left for France.

It is about 6 o'clock in the morning, and we are in the rest trenches due to go into the firing line for four hours...You turn over, and in so doing dislodge some dirt in your dugout which of course falls into your ear and mouth. Further sleep out of the question by the time you have emptied your mouth, so you get up but do not bother dressing as the situation demands that you sleep fully dressed. Being in charge of a platoon you look up your orderly roster and find who is orderly for the day. You should have done this last night, only the excitement of writing to the "one and only" caused you to forget... Breakfast comes up... a kerosene tin full of tea and tea leaves floating about on top, and a swarm of flies buzzing about. On examination the tea leaves prove to be flies, and you get seven with your share of tea, and a dixie with fried bacon and bully beef which is very salt. It's your platoon's turn for cookhouse fatigue. This is very hard and disagreeable fatigue. A large quantity of water has to be carried half a mile from the tanks in Shrapnel Gully up to the cookhouse and wood has to be hunted for to cook it with, so it's an all day job. It falls to James and Brown... Always growling, but they get there all the same. The finest regiment in the world wouldn't have done more than the wild, undisciplined mob did in the landing, and again at Lone Pine; and an intelligent officer can get anything out of the men if he himself is a man.

Nine am arrives and we move off along the communication trenches to our position in the newly captured Lone Pine. We are a wild-looking mob. Dusty faces, unshaved--about six weeks to three months growth... In looking along a ridge, my optics discern an Abdul [a Turk] on the slope. I put up 575 and squint, but immediately seventeen flies make a frontal attack on my eye and nose, while two further bodies attack my ears. To save myself from choking I swallow four flies alive. Retire temporarily to put on a fly veil and again squint along the sights. This time seven flies are fighting over some jam on my backsight, whilst another one is preening himself on my fore-sight... Eventually our midday and chief meal arrives. Bully beef stew, with preserved spuds for vegetables. Very good too only it's horribly salt. The tea is also very acceptable after you skim the flies off.

"There's Abdul again blarst him," someone says as a heavy explosion occurs and the peculiar pungent smell that comes from a bomb [hand grenade] reaches us... The day passes without further incident until our tea arrives. Boiled rice and raisins and tins of tea, both of which are liberally flavoured with flies; also bread and jam. Hold an inquest on the rice and raisins, and then bury it decently by throwing it over to Abdul. Eat my bread and jam thoughtfully.

The night passes very slowly. About midnight a Turkish machine-gun viciously spits out about 100 rounds in about 17 seconds, and then their whole line springs into life. Peer over the top. Little jets of flame are appearing and disappearing everywhere along our front. Slip along to the bombs. The throwers are there ready, so return with an easy mind. There is a steady steady stream of bullets flying overhead or striking the parapets. Above the rifle fire you can hear the incessant crackle of the machine guns. Further along you hear bombs. We do not reply to the rifle fire, and our machine guns keep silent. We just sit tight and wait. There are no points in disclosing your M.G's possys [machine gun positions] just to get them shelled next morning. If Abdul climbed out of his trenches, then there'd be something doing, but until he does we just wait. After an hour or so the firing died down and there was only an occasional shot. We had to keep very wakeful all night, or else risk being shot for sleeping at our posts, or perhaps get blown up through a bomb settling nearby without one's knowledge. In unprotected parts of our trenches where bombs are frequent, we have blanket men stationed at each post. They have a double blanket folded into quarters, which they throw over any bomb that comes into their domain. We get roused up thoroughly every morning an hour before daybreak and everyone "stands to" in readiness till daylight. This happens every morning. After the stand to we are relieved and retire into the shelters. After brecker [breakfast] the 75's or pip-squeaks start again.

Liverpool Camp

Viv and Percy were at Liverpool Camp with time on their hands in between non-com classes, drill and various duties. At night Percy knelt and said his prayers, believing it to be the right thing to do and thankful for being given the strength to ignore the jibes which soon stopped. Percy knew that he was thought of as "straitlaced". Percy wrote letters and continued his diary, also sketched and studied. Both boys were soon promoted to sergeant, the third rank. When they were given leave Percy went to Taree to say goodbye to friends there and Viv and Clytie went to Kiama for a week's honeymoon.

At last there was some musketry practice and they both did fairly well. At 500 yards [450m] with a nasty wind blowing Viv got a score of sixteen, and Percy got seventeen, the best score at the range. In his diary Percy wrote:

About 4 pm I was sent to take Viv's place on the isolation guard, as he was wanted. I was the only non-com [non-commissioned officer] and the men I had were not much chop. We had three prisoners and had to keep the inmates from breaking out. The prisoners' language was vile. Viv came along and said the exam results were out. Both now serjeants (sic). Left Drain in charge of the guard and took patients to be treated for VD, the due reward of their misdeeds. Got back with prisoners in time to take out 7.30 relief. Two MP's [military police] arrived with another prisoner who had tried to escape. When the rounds had come, Drain didn't go forward when they called for the man in charge. Someone said that the serjeant of the guard had gone away somewhere. The serjeant-major came to the conclusion that nobody was in charge. This however I didn't know until later. I was to appear before the court at 8.45am in the morning with the men against whom the charges would be made. I would not fall in over it

Took the men down to the court. The case was nearly the last to come off. When our case came on, the charges were read to me. I was charged with (1) neglect of duty, and (2) allowing a prisoner to escape while in charge of isolation guard. I stated I had distinctly warned Drain to be in charge of the guard while I was at the "irrigation". When asked for witnesses to corroborate my statements, I had none as I had acted on the advice of the police and didn't expect this turn of events. I was reduced to the ranks and fined a week's pay. I was thunderstruck. It was a very severe blow to me. The rank injustice of the whole thing stirred up my wrath and indignation. I asked Tyson if I could appeal or get a trial by court martial. He would make enquiries. Saw our old officer in command and he said he would look up the regulations. Went to bed early being tired and worried. Felt dreadfully downhearted and miserable. Today's turn of events was the hardest knock I've had for a long time. Asked Viv to doss in with me, and we put both blankets together, and thus cheated the cold.

July, Tues 1. Tyson dictated a letter for me to write asking for my case to be re-opened, as I considered I had been unjustly dealt with, and hadn't been given the option for a court martial. Looked up 'King's Regs' [Regulations] to see if they have the right to reduce a non-com to the ranks.

The next day Percy went back to the ranks without waiting for orders, feeling indignant about irrational behaviour. While Percy was on guard duty, Tyson sent for him to go with him to the orderly tent, to see about the case being reopened. They were taken to Kirkland who was very uncivil and piggish in his manner. I asked if there was any chance of getting a court martial, to which he replied that I was not entitled to one. He then told me that I was not a serjeant at the time of the trouble [It was not yet gazetted.] He said that putting in the application for retrial was an act of unsubordination, and showed that I was flouting his judgment...The case could be re-opened a few days before we leave.

A few days later they were awoken at half past three at night by someone rapping along the corrugated iron walls of the hut to go and re-enact the landing at Gallipoli for a picture film company. The Minister for Defence gave support to films being made, calculated to attract volunteers. A previous attempt had been a failure, because when the operator called out for every fourth man to fall dead, "the whole crowd went down to it." After breakfast they marched to Liverpool and took a special train.

As we neared Sydney day began to dawn. The train was blocked at one place and a few people in the houses below saw the troops and started waving at us. Another train somewhere nearby was whistling its inside out with a variety of spasmodic blasts and I wondered what was wrong with it. Then we moved on and soon another engine seemed to go mad and started demonstrating its whistling powers. Then I tumbled to it. They were cheering us. More trains came by and almost blew their whistles off, while our boys answered with cheers and shouts. Soon we approached the engine sheds at Redfern, and engine after engine joined in the mad chorus, shrieking and screeching, till the hundreds of engines and even the old steam cranes contributed their share towards the general din. As we rumbled through Redfern, men quickly gathered on the platform to cheer and wave to us, sharing in the general delusion that we were leaving Australia.

We marched from the station down through College St, up William St and out past Rushcutters Bay to some Navy place, where we had sausages left by the sailors and plenty of bread and jam and tea with milk in it.

About 9am we fell in again and were put into boats and taken in tow by motor launches to Middle Head. After some time we were landed on the tiny beach at Obelisk Bay. A company of men there were dressed in the Turkish uniform. Some land mines were placed in the sand on the beach and connected up by wires, to be exploded by electricity. After a while we got into the boats again. We put off a bit and got ready for the great event. The Turks were placed, some on the beach and some further up the hill. The cinema camera was placed on a rock. When everything was ready, we got the command to fix bayonets. Things began to get exciting. The troops on shore opened fire and some bombs began to explode, and for some time there was quite a respectable din. As our boat ran up on the sand, we sprang out and charged up the hill with bayonets fixed. A lot of men and some Turks had fallen dead on the beach. I charged up the hill till the whistle blew without noticing myself getting particularly tired. But when we stopped I was almost exhausted, although it was only quite a short distance. We had full kit on and the hill was steep.

A couple of chaps acted a struggle on the cliff between an Australian and a Turk. A brief struggle followed and the Turk lay helpless. He got up and a stuffed dummy was put in his place. The brave Australian then picked up the dummy and shot him over the cliff with truly wonderful ease. That ended the play. It didn't appear to me to be too well done, but might look alright on the pictures.

Percy had arranged for a sewing machine he had used in tailoring, to be sold in Dungog, and his father had used the money to make a start in his new shop at Kogarah. Percy also arranged for ten shillings every month out of his pay to go to Foreign Missions. Rita gave him a face cloth she had knitted, wrapped in brown paper on which all sorts of messages for Bert and Vernie were written. He had got Viola to get him paints and brushes. He approached Tyson for help with his demotion and loss of thirty-five shillings fine from his pay, but it was now too late, they were leaving in the morning.

The next day he was up again at half past three. He said goodbye to Viv who was staying for further training. They all had flags for the ends of their rifles, and black and gold ribbons. As before, the engines woke up and worked their whistles overtime.

Percy

Percy

When we arrived at Sydney there was a large crowd waiting. I kept a sharp lookout for Mum and the others, but couldn't see them. Many of the onlookers broke into the ranks, and came along with their friends and relatives... We walked along any old how. Met Dad at Rawson Place. He had sent the others on by tram to Fort MacQuarrie, thinking they had missed us. Came across Mum and the children near Fort MacQuarrie. Poor old Mum seemed to be rather cut up. The big "Orsova" was alongside the wharf, waiting. I hung back until the last, and then said Goodbye to them all. It was rather a trying time. People were crying everywhere. Gave my flag to Mum to keep till we come back from the war. Viola gave me a small bouquet of wattle. We were at last sent on board and had our quarters allotted to us. Then we were allowed out on deck. The side of the ship was lined with soldiers waiting for their friends and relatives to be allowed in on the wharf. At last the big iron gates swung open and the crowd came pouring in. Almost at the same time the great vessel began to throb, and to move slowly, ever so slowly... In vain I looked for Mum and the others... Packets and parcels were thrown to friends on the ship, streamer reels of all colours were tossed on board. The wharf soon became packed and a fantastic maze of many coloured streamers connected the slow-moving leviathan with the throng below. Further and further out we got, while I kept searching anxiously among the thousands of upturned faces. How I longed for a last glance at the familiar faces - to be able to wave them a last farewell, but it was all in vain. The distance increased, and streamer after streamer reached its limit and broke asunder. I felt bitterly disappointed, and could not help crying a bit. On the wharf hundreds of flags and handkerchiefs were fluttering and waving, and the air vibrated with the continuous cheering. It was a pretty scene, yet solemn and awful. Slowly the distance increased, and the network of gay streamers dwindled away, till at last a solitary purple ribbon stretched from the stern to the wharf, a distance of about two hundred yards. Gradually our pace increased, and the crowds left the wharf and followed us along the shores of the bay, still cheering and waving.

The great ship moved on down the harbour for a while and then came to a stop. A few motor launches followed us with passengers, and I scanned them eagerly as they came past. At last I thought I spotted Mum. Yes it was her alright. She and Dad were standing at the stern of a pretty crowded launch. I got in a prominent position and waved and waved till at last I attracted their attention. The three girls and Gordon were there too, on the top of the launch. By-and-bye it came so close that we could talk to each other. The girls asked me to send them postcards of France if we go there. Rita tossed up a flag for me to keep. The launch kept about for over half an hour, and then began to move off. We kept on waving till she disappeared past the stern of the ship. I was glad the parting was over, and happy that I had been able to see them again in the launch.

As soon as possible after arriving in Egypt he took a train to Cairo to see the lists of killed and wounded in case Bert or Vern was on it. For weeks he continued to watch, not sure whether his brothers were at Gallipoli or "Blighty".

A number of their cousins and second cousins had enlisted to fight for their grandfathers' and great grandfathers' "Motherland". On 7th August their second cousin corporal Hubert Roulstone Clifford Currie (grandson of James) of the 8th Light Horse Regiment was killed in action at Gallipoli. Even the boys in the “Billabong” books joined up.

Tyson said he intended to put Percy into the first vacancy for sergeant. A week later Percy went to see the pyramids, then was sent to Lemnos and to Gallipoli, landing at Anzac Cove while the Lone Pine Campaign was under way. The day after Percy's arrival, Bert, back from Blighty, found him sitting in his trench writing his diary. The three brothers met in the dugouts at Shrapnel Gully. Percy thought Bert looked a bit unkempt and Vern a bit pale. As none of them smoked they gave their cigarette allowance to friends from home.

Vern

Vern

Vern had been mentioned in despatches, which was incorrectly reported as a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) and later by Bean, the official historian as a Military Cross (MC). It was for repairing a phone line across the territory between enemy fire. The line was vital because Lone Pine was in a commanding position on a ridge where the Turks had underground trenches with logs on top for protection. A few days later Vern's officer was hit in the throat and taken out of the trenches with no-one available to replace him. Vern aged twenty took over in the emergency. General Hamilton mentioned him in despatches and in spite of his youth he was again promoted. He was a lieutenant, the fifth rank and was described as "short in stature, trim of build and dapper in appearance. His face had the frank open expression of a healthy schoolboy." He liked to carry a baton and always looked tidy. He was well liked and known as a very quick-witted person, even jocular.

When Percy saw Vern he suggested that Vern should send more money home in the light of his promotion. Vern said that he didn't know his parents needed any more but he would allot an extra six shillings a day. Bert also made a similar arrangement.

One day during September Percy saw that Bert was not well so he cooked him some rice with sugar and milk, which his brother managed to eat. Soon afterwards Bert and Vern left the peninsula for a spell. Bert was re-admitted to hospital, then to the Australia Depot in England and later to the 1st Training Battalion. In the next few days both his brothers and their mother would be celebrating birthdays so Percy wrote to them.

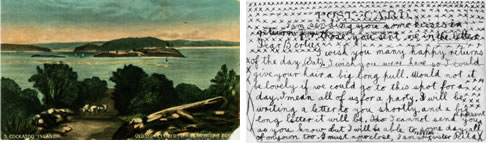

A postcard, which Rita sent to her oldest brother said:

Dear Bertie, I wish you many happy returns of the day (Sat). I wish you were here so I could give your hair a big long pull. Would not it be lovely if we could go to this spot for a day. I mean all of us for a party. I will be writing a letter to you shortly, and a big long letter it will be. I cannot send you a present as you know but I will be able to some day, all of my own too. I must close now, I am your LOVING sister, Rita. I am sending you some kisses in return for those you sent me in the letter.

And she covered every available spot with crosses (kisses).

It was a picture of Cockatoo Island painted a hundred years earlier, when the island had been in its natural state, "32 acres of rock infested by snakes", not even considered worthy to be named on the official maps. Since then it had become a place to send convicts, a female reformatory and later a part had become a dry dock. In 1910 the shipyards were expanded and during the war destroyers and cruisers were built there, the cruiser "Brisbane" being the most recent. Rita chose the postcard because she had seen the island often when they lived at Gladesville and thought it looked a lovely place for a picnic.

Percy, now a corporal, was growing a moustache. It was thought that a moustache gave an air of authority. A week or so later he went to the doctor feeling sick. He was not believed and had to parade with the malingerers on extra fatigue duty. But the officers saw that he really was ill. Finally he was taken to the Island of Malta by hospital ship. Although he had suffered a lot from diarrhoea and headaches from the noise of the shelling, he was healthy enough to survive double pneumonia. He hoped to get to England to convalesce, a "Blighty".

While convalescing he began to try writing short stories to help fill in time, also did some sketching and even started teaching himself French and shorthand, which he used in later stories. Although some of the men ridiculed him he did exercises regularly to help him get his strength back. Even though he wrote frequent letters home to his family and friends, few of the eagerly awaited letters to him arrived. During this time he went for long walks and was able to enjoy some of the sights of the island, and the town of Valetta with its interesting palace-museum. When finally he was due to be released there was an outbreak of diphtheria causing quarantine until after the evacuation of Gallipoli.

In his diary on 30th December he wrote:

Well here ends the year 1915, in warfare, sorrow & misery. Am getting very unhappy for dreadful possibilities are beginning to force themselves upon my mind in regard to Bert & Viv. If only I could get some news of them. The suspense is the worst part of it.

At times the inactivity was depressing. He wrote:

I felt blue. The hopes & dreams of my younger days seemed to rise up & mock me. What advance had I made towards the perfection I used to dream of? I had thought by this age to have overcome all the faults in my nature that were of any consequence, & not only that, but to have also become a powerful influence for good. And what advance had I made? Not much I'm afraid. Am I to go on through life to the grave as just an ordinary man, living more or less for himself, & doing no particular good in the world? I felt very discouraged, & even the thought of the success of others only seemed to accentuate my incapability. I believe I have brains enough to make some use of but qualities of will-power & stick-at-it-iveness are sadly lacking.

Ramsgate to Egypt

Viv

VivBefore leaving Australia, Viv made allotments to his mother and Clytie. As he qualified as a second lieutenant, earning fifteen shillings a day on 2nd September he could readily afford two allotments. As part of his training he did some boxing and at times refereed boxing matches. Clytie was working one day a week at five different schools giving her parents' address at Pennant Hills where they had moved before she and Viv married. Married women were obliged to resign, so she began demonstrations of gas cooking at town halls and other venues for the Gaslight Company. At the end of the year Viv sailed with the 17th battalion for Egypt for further training. By this time Clytie was pregnant. This would be the first Smythe grandchild.

Meantime at college Viola failed in setting words to music, Ida failed mathematics and Rita aged thirteen had come top of her class at Fort Street. Rita had always done well at school until one day at the school sports, which she always enjoyed, she felt that she "overdid" it. The next week she became ill with chorea. There was no treatment except complete rest for a long period, good food and no worries or stress. It was usually not fatal, but often resulted in a rheumatic heart condition, damage to the valves of the heart. Her mother, limping on her bad leg had to half carry her to the tram to visit the doctor. After one year at high school Rita fervently regretted it but felt unable to continue.

At Ramsgate, the lawn which Percy had planted was coming on well and a number of ducklings had hatched. Very proud and elated, the Smythes had heard that Vern had been awarded an MC (Military Cross), which was premature*.

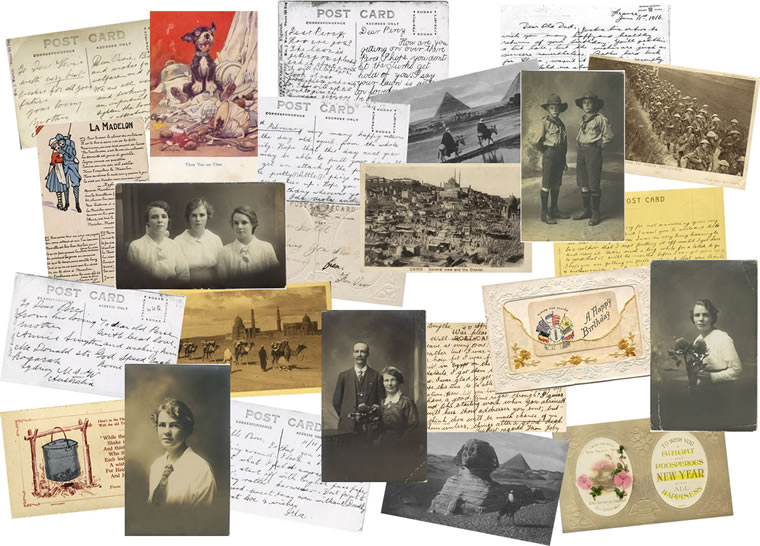

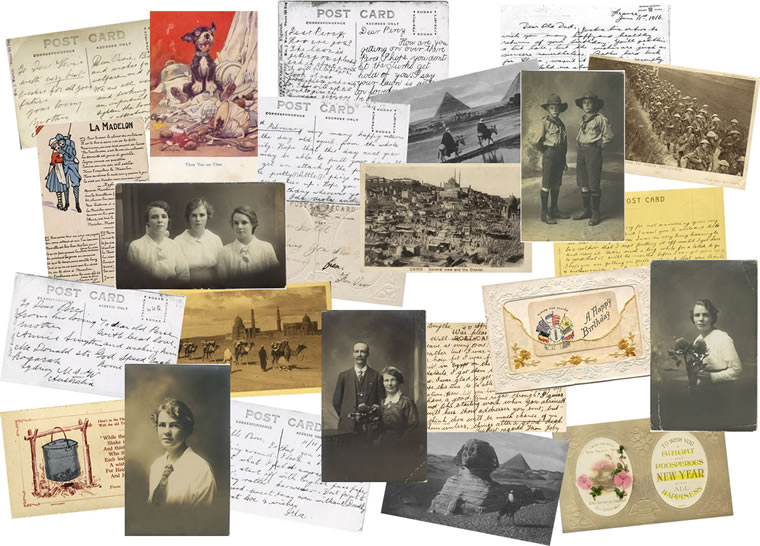

They had photos taken to send to each of the boys at the front, one of Ted and Annie, one of the two younger boys in their Scout uniforms, one of the three girls together as well as the girls separately.

Annie was fifty-five, Ted fifty-seven. Annie wore glasses, was very dressed up and still had a full head of dark hair, cut short in the fashion of the times. Ted wore a dark suit and waistcoat and watch chain, his hairline was receding but he had grown a large moustache.

On the back of a photo of their parents was the whimsical message (possibly in answer to a similar one from him)

To my dear son Vern from his loving Mumsie and To Dear old Vernie with best love and wishing him God Speed back home, Dad.

On the back of their photo Eric aged eleven and Gordon nine wrote:

Dear Vern, Glad to hear you are recommended for a captaincy. Mind when you come back you'll have to tell me how you got the M.C. In the next letter tell us how many turks you killed. You'll be killing germans soon. You'll know our frontispiece with best love from Eric. XXX

Dear Vern, Have you made an end to any Turks yet? Do you chase them with a dead cat or with gun and bayonet? I don't care what you chase them with as long as you kill them. XXX from Gordon XX.

Returning to Egypt after his illness, Percy was near Vern and Viv. He thought Vern looked "some style in his officer's uniform". The youngest of the brothers was making remarkable progress in his military career. Vern allowed Percy to read his letters. Percy had written many but had still received very few. Mail was very important; news from home was only surpassed by new socks, hand-knitted of course.

As there was trouble with Arabs, Viv was transferred to Tel-El-Kebir so Percy did not see him. They heard that Bert had chronic bronchitis and might be sent home.

Just after his twenty-third birthday and before he left Egypt, Percy received two large packets containing fifty letters, including belated Christmas cards, returned short stories, some mail from friends and many from his family including the photos. He thought his father looked thin but his mother looked better than he had ever seen her.

After further training in Egypt, Viv as a second lieutenant was posted to the 24th Battalion, just before the embarkation of this unit for France. He was one of several youthful officers promoted on ability, unlike their British counterparts.

In March Percy rejoined his unit at Tel-el-Kebir, was promoted to lance corporal. In preparation for embarkation for France he sent home another diary and sketches he had done. Edward the Prince of Wales came to inspect the AIF and Percy thought he looked very young and shy, although he was only a year younger than Percy.

At last they were away from the heat and sand of Egypt. The chances of being sent to "Blighty" if injured were thought to be greater from France than from the Middle East; an added appeal.

France

The AIF began to move the troops from Egypt to Marseilles and then by train to the north coast area of France to protect the ports and to distract attention from the Somme ("The Western Front") where the main offensive would be. On the way Percy made sketches and tried out his French but could not understand the answer.

In the nearby villages were shops and people and even children. Peasants continued to tend their fields while the soldiers could have baths and disinfect their clothes and bodies against lice and other vermin. Tension was less than at Gallipoli and sniping less keen, but there was little protection from shells as the trenches in the north were not very deep in the naturally water-logged ground and any excavation immediately filled with water.

In France the soldiers were issued with tin hats and gas masks and were given drill in using the respirators. They had to breathe in through the nose and out through the mouth so that air passed through material saturated with chemicals to purify it. There were several gas alarms, which were a "frost" or false alarm. Gas caused watering and burning of the eyes, blindness, bronchitis. Use of gas depended on wind direction, which could change and blow it back.

At every opportunity Percy went to the nearby towns and was especially interested in the cathedrals, admiring the stonework and paintings. Once, not knowing it was forbidden to leave the billets, Percy went sightseeing, was caught and again demoted.

In early 1916 Viv, Percy and Vern were all in this area of France, near the Belgium border, northwest of Armentières, and they managed to see each other. Finally the showerproof overcoat which Bert had sent in early February, reached Percy who found it "bonzer". Mail was most unreliable. One parcel from Annie to Bert had gone from Egypt to France where Percy re-addressed it to Mrs Morgan. Mrs Morgan wrote to Annie "You see my address for Bert is most safe. I send his letter on for my Percy to read & tell him to let yr Percy know."

Percy Smythe wrote that Viv had a Charlie Chaplin moustache "like mine". He bought a book of French and continued to teach himself, often writing a few French sentences in his diary or a letter to Ida who was learning French at school. He also sent home money for a gift for "the expected newcomer". News came through that Clytie had a two-month premature stillborn baby girl. Stillborn babies could not be buried in a consecrated cemetery as they had never lived and could not be christened or have a religious ceremony. Previously they would have been buried on a family property in a private cemetery, such as on the farm at Winton, Victoria.

Vern

Vern

In May Vern aged twenty-one, became a captain. He was reputed to be a good officer, well respected by his men. He said he would never ask them to do something which he would not.

On one occasion two staff officers came to Vern's trench to discuss plans. They left in daylight against Vern's advice. When they did not arrive back at their own trenches a telephone message, sent by the officers seeking assistance, came to Vern, who still refused to send men out into exposed positions before dark. One of the officers, quite exhausted, eventually arrived at headquarters, the other was finally found in a shell-hole up to his waist in mud, sinking further if he struggled. They got stretcher-poles under his arms and four men lifted out the brigade major, caked in mud but minus his boots and pants.

Percy had volunteered to learn the use of the recently available Lewis machine gun. Classes were five hours a day for several days, after which Percy got a First Class pass. Lewis Guns at 28 pounds were comparatively light. Sometimes they had to be carried as well as the regular kit.

He wrote that he had met his cousins from Tasmania, Ern Graham aged twenty-four, a lance corporal in Transport and his nineteen-year old brother Alf who was small and thin. They had enlisted in August the year before.

The first major battle in France involving Australian troops occurred at this time involving enormous loss of life and many casualties being left for the Germans to bury in a huge common grave. In July, during the battle of Fromelles, which was regarded as a great blunder, some troops had advanced north and were cut off and awaiting the order to withdraw. The Australians had no grenades and their rifle ammunition was running low. They felt they were deserted without hope of rescue, as the real offensive had begun in the Somme area. Some were captured. Vern called for volunteers to dig trenches four to six feet deep across no-man's-land and duckboard them without being seen. At first the response was nil. To encourage them he stood with assumed nonchalance on the parapet of the trench, and when a machine-gun began firing still did not jump down to take cover. He insisted that the gun could not traverse quickly, as the belt had to be kept straight. He counted and knew exactly when he should retreat. It was calculated and not foolhardy; intended to reassure nervous men. An artillery barrage, usually a prelude to advancing, was arranged to provide covering fire and when the order came, the men were able to retreat. Vern won an MC. This time it was awarded.

Pozieres, July

Bert

BertBert had done a special course in instructing and became part of the First Training Battalion. He was now teaching signalling, regarded as an expert in semaphore and got 299.5 out of 300 in signalling, beating everyone including the officers. After some time he began to feel that his younger brothers were getting promotions and decorations. Vern had been promoted at a very young age, and had been decorated, while he, Bert, was twenty-six and still only a sergeant.

The Somme was a sluggish stream, which rose near St Quentin, France and split into numerous swampy waterways passing between chalk plains, where it was difficult to dig trenches that were not very obvious to the enemy.

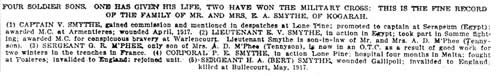

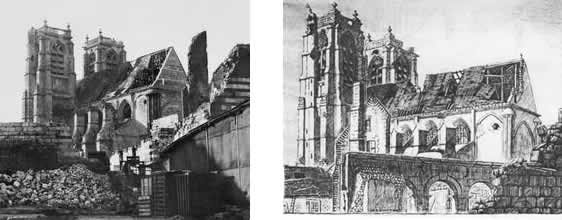

Pozières had been a small neat village near Albert in the Somme area, amid the roses and poppies of Picardy. Percy's impression of Picardy was of beautiful fields resplendent with a wealth of glorious colour, fire-red poppies blazing up from the rich green of lucerne or bordering the crops of wheat or rye, numberless cornflowers adding their beautiful blue to the colour scheme, and various other flowers of heliotrope, yellow or white, gracing the countryside with their presence. But the poppies were the most beautiful of all. Their silky petals looked like so many flakes of fire. It is such a beautiful country, and the weather has been so delightful, and everything so calm and peaceful that one can scarcely realise that a death struggle between the nations is going on only a few miles away.

Many battalions were sent to the area. While billeted near Amiens, Percy made some unauthorised visits to the city, which greatly impressed him, especially the cathedral.

Gas was used and was at first thought to be shells striking soft mud with a distinctive muted thud. Those men who wore gas masks suffered from a lack of air and sickness, which caused them to tear off the mask, their eyes streaming from the effects of the gas. In mid 1916 Percy's battalion was sent to the Somme. Percy had also been able to meet and speak to Perce Morgan. After the Battle of Fromelles Vern and the 56th battalion were marched there. Viv and the 24th battalion also arrived.

Both sides were determined to take the strategic village of Pozières. It was intensely fought over in mid 1916 and obliterated to a heap of rubble and shell holes by German artillery as they retreated. The officers wondered whether they should allow the dead to lie unburied, which was demoralising, or risk more deaths to bury them. For an hour each day Red Cross flags were used by stretcher-bearers of both sides.

Post traumatic stress was commonly called shell shock. Perce Morgan was buried to his neck and while they were digging him out another shell came and blew his head off. In desperation Percy tried a cigarette and rum to get through the horrors, but apparently it did not help; he never did become a smoker or drinker. He wrote to Mrs Morgan sending his condolences and she replied asking for details of her son's death. Percy replied as well as he could.

On the eve of a battle Viv wrote to Clytie

My Sweetheart and Wife,

How are you keeping both in health and spirits? Well and happy I hope. But I would so like to go home and make sure. I would just give anything to see that look of love and joy spring to your dear eyes again as it used to do in those short but sweet days so many age-long months ago...

For nearly two years the war had raged in that area with little advance on either side. Viv felt ill inside having to send out patrols, knowing that many men would not return. While in France he also suffered from severe hay fever.

The fighting around Pozières continued. After a tiring march from the Brickfields west of Albert, the sixth brigade arrived at nine o'clock at night. On arrival they had passed through an artillery barrage, then had settled with half the men in the front line and half in close support, mainly along "K" trench. Two battalions in the rear were in reserve, acting as carriers of food and supplies to the lines. The units were at full strength and the trenches were consequently crowded when a bombardment began. At first most of the shells passed over the front line, but as the day went on, the aim was corrected and by the afternoon trench mortar bombs and shells were bursting in the trenches. Without deep dugouts, only small recesses, Viv's battalion, the 24th in "K" trench was murderously hit. The dead could not be buried. The survivors could do nothing but wait. They waited to be either killed or else buried by collapsing banks. Tormented by lice in hair, socks and clothing in the trenches they sat for hour after hour. To help keep up morale Viv passed along "K" trench and saw four men playing cards. According to Bean, the official historian:

The officer passing along the trench in the afternoon, sickened by the sight of the dead and wounded, saw the body of a sergeant which had been lifted out of the trench above the spot where four men were dealing their cards. "You've lost your sergeant I see," remarked the officer to the group. "Yes" replied one of the men in a voice which failed in its attempt to conceal the speaker's emotion. "He was playing cards here with us a few minutes ago when he was hit." Another man had taken the sergeant's hand, brave men played on hardly knowing what cards they dealt, struggling against their feelings, trying by a display of apparent coolness to steady the nerves of others.

Viv

Viv

When Viv came back fifteen minutes later they were all dead. Viv said this was his worst experience of the war. He had not been at Gallipoli but those who were, said that in this single battle, divisions were subjected to greater stress than the whole of the Gallipoli campaign, with greater loss of life. But this struggle enabled the Allies to advance to the next position.

Mouquet Farm

The next month Viv was involved in fighting at Mouquet Farm, a mile away. It was reported that the Germans were attacking from the farm and north of it. The Germans had built a reinforced blockhouse, half underground with walls four feet thick. It was frequently hit by shells of light calibre, which didn't cause worthwhile damage. It could only be put out of action by a direct shell. Isolated troops were in a desperate position. Brigadier Gellibrand ordered the 24th Battalion to suppress the enemy in the farm by two bombing attacks from the south and southeast.

This perilous duty was accepted by Lieutenant Smythe [Viv] and parties were organised: but as the artillery could not be employed for fear of hitting the isolated troops, and the available trench-mortars were in positions from which the objective could not be hit, the order was at the last minute cancelled. The abandonment was fortunate. It is unbelievable that it had any chance of success. (Bean)

However it inspired someone to write a piece of doggerel "How the Farm took Mookay Bill” and Viv acquired the nickname Mouquet Bill. He had souvenired a German helmet as a memento of the event. There could never be another such war and souvenirs would be of great curiosity value. Although the Germans attempted a similar attack to assist their troops, they were easily driven back by Stokes mortar and Lewis guns. This was one of a number of salient points on a wide front. Casualties were the greatest ever suffered by the Anzacs. In seven weeks there were 23,000 AIF casualties. By now the whole area was nothing but craters with no sign of the farm or village. The strain of the battle required a new approach to discipline.

Machine Gunner

Percy wrote an account of his experiences which was published in the Jerilderie Herald:

A week ago I was one of a machine-gun crew of nine men, and now am the only one left. Five were killed, one wounded, and two missing (probably killed) and even the gun was blown up. We went into action just after midnight on Sunday morning. Our battalion was in support to the 1st, which made the charge, and I was in the reserve machine-gunners - a rotten job, as the reserves generally get the worst of the shelling. Soon after the fray started we got a false order to fall back, causing no end of confusion. Two of my crew were killed about this time, and two were not seen since. We had nothing to do but put up with the shelling and wait until we should be required in the firing line. Went to sleep in a bit of a hole, which was supposed to be a dugout and awoke later to find myself buried to the armpits. A shell had blown my dugout in. Got my head out and called for someone to come and dig me out, after which I went to the dugout of another chap of my crew. A few minutes later a shrapnel shell wounded him in the leg and killed another fellow alongside. Bandaged his leg up, and as he was suffering a good deal of pain I let him have the dug-out to himself, and as accommodation was difficult to find, had to share a dug-out with a corpse, and in spite of the grim presence slept soundly. Things were comparatively quiet all Sunday, in the afternoon I suddenly awoke under the impression that something was biting my leg, and found a small piece of shrapnel sticking into it through the puttees, she stung some too. In the evening two of my gun crew and I got together in a bit of a trench which was not much used. As it afforded a little protection we collected haversacks and water bottles left behind by wounded men, and fared well, our victuals including sweet biscuits, bread, butter, jam, cheese bacon, sardines and chocolates. We slept there and stayed there together all Monday morning. On Monday Fritz [the Germans] bombarded the village of Pozières where our front line was, and he was using some big shells too, sometimes, and we could see great branches of trees go hurtling skywards... During that night the remaining three of my gun crew were either blown up or buried, I stood the nervous strain well, and came through smiling until I took a hand in digging out some buried men, which is the most heart-breaking task I've ever had. Four men were buried in the communication trench and I went to their assistance and worked for dear life. Am not strong physically, and it played up with me a treat. Rescued one chap who was completely buried except his face and the fingers of one hand. While we were working a big shell landed near by knocking two of the workers, one beside me staggered back and fell, and I thought he was killed, but fortunately it was only a wound in the face. Two of the buried men were got out alright, but the other two were deeply covered, and it took nearly an hours solid work to get them out. The other chaps were for giving them for lost, but I urged them on hoping it might be possible to effect resuscitation. Could not bear to let them go while there was any hope of saving them. Tried to set up artificial respiration with one of them, but could not manage it so went and called up the doctor. Left the job to him and went back to the firing line. Have not heard how he got on with them... It was a relief to us when daylight came, especially as we were to be relieved in the morning. A Coy [Company] was without officers and practically devoid of non-coms, and a number of the men breaking down under the nerve strain left and went back to the rear. Every man wounded was regarded as being very lucky. I saw a madman rambling down the communication trench trying to catch hold of something he could see in the air, and I envied him. A prisoner was brought in and his face was thin and pale and drawn and we pitied him the poor beggar. A sergeant wanted to kill him, but we would not hear of it. In our own affliction we could well sympathise even with our enemies. At some time after daybreak there was a lull, and we began to hope Fritz had taken a tumble to himself... The bombardment up till this time is reckoned to be equal to anything known at Verdun, but one could not describe what followed. It was the lull before the storm. A salvo of four big shells came over, and then the place was converted into an absolute HELL. It was awful. It seemed as if the whole face of the earth was being churned up. Clouds of earth and branches of trees were hurled skywards, while clods and lumps of chalk were falling all round. When a shell came near the dense clouds of black smoke converted daylight into darkness, and the smell and the smuts were vile, but worst of all was the terrifying nerve-racking roar of the explosion, which was indescribable. Out in front the same storm of shells raged... we ran forward through the heaps of smashed brick and splintered timber, which had once been Pozières. Found some more of the gunners and stowed ourselves in shell craters, but the place was untenable... There were remnants of a hedge, and beyond that open fields, where no shells were falling. We got out into the fields and made for the narrow strip of wood about three or four hundred yards away, and then Fritz spotted us and bullets came flying all around. His shooting was very erratic, however, for we all got safely into the belt of timber. Our own artillery which for some reason had been silent all the morning, at last opened out and to our exasperation began landing shells all round us. The mistake must have been reported by our aeroplanes, for after a while they left us in peace. Our nerves were considerably affected, and we would get jumpy if a shell lobbed 50 yards away. We stayed in the wood all day, and got back to the 3rd line trench under cover of darkness, stayed there for a night and next day the battalion was withdrawn from the trenches and we came right out to beyond Albert.

This experience inspired him later to put his thoughts into a poem called:

A Memory

The flautist played: and music, sweet and low,

With soft caresses old-time memories woke,

And long past scenes from bonds of lethe broke.

And I beheld red poppies all aglow

Like fiery mantle drape the earth below:

I heard a heaven-rending sound that broke

The still of dawn, while sable clouds of smoke

Plunged dark and reeking round a scene of woe.

Men cower trembling in a shattered trench,

Unnerved with noise and blood and foul smoke-gust,

While shrieking shreds of steel through soft flesh tear.

Brains frenzied reel: stark hands in death-throes clench.

The whole creation's blasted into dust.

Hell's fury falls on shuddering Pozières.

Viv and Clytie 1916

Clytie

Clytie Viv still anticipated being home in a few months when Clytie on maternity leave, had given birth to a two-month premature baby girl who was stillborn, there was a family conspiracy to keep the news from Viv for fear of distracting him in a time of danger. Of course he was aware of some problem and expressed disappointment that they did not trust him to cope with the news. Single-mindedly Clytie was negotiating to build a house on land that she had bought near her parents at Pennant Hills, Sydney. Viv's military pay allotments and her own earnings had been faithfully dedicated to her dream - to build a safe refuge for her hero-husband when he returned. Her parents were also building in the same street. Determined and well-organised Clytie went ahead with her building plans. When her house at Pennant Hills was finished she intended to call it "The Haven" and await the day when Viv would find it a haven from the trenches. Although the sewer was not available and would not be for another sixty years she was required to build a room for a flush toilet as part of the house!

Viv's parents had also been able to make an addition to KY at Ramsgate by hiring a builder to put on a bathroom with rough plastered walls, cement tubs and copper, at a total cost of £27 for labour and materials. They paid a deposit of £15 and made final payments within weeks. It cost them £4.7.0. to have the back veranda boarded up as the boys' bedroom. In front of the house they planted a vine, which grew prolifically. They planted two little camphor laurel trees in the tiny front garden and a tree fern near the back veranda, and planned to get the name “Koppin Yarratt” made. At the same time Ida and Viola were having pianoforte tuition, which cost £1.17.6. per quarter.

After months of rest Rita was, according to Percy's diary "almost well again", but they were aware of possible damage to her heart. In June she had left school "through illness." Percy also noted that his Uncle Arthur aged forty-five from North Winton was anxious to get away to the war. It might arouse his interest & ambition a bit if he did. He is only wasting his life stuck there on that old farm.

Extremely proud of having four sons fighting for the Motherland but also apprehensive about their safety, Ted was still seeking comfort in a little too much alcohol. He was still a tease, gave his younger children little lectures on manners and behaviour and was openly admiring of their successes and efforts. He was strong on family ties, having lost his mother as a little boy and his father as a youth.

The population of Australia had now grown to five million. From Rocky Point, (Sans Souci) a ferry service began from the end of the tramline across the George's River to Taren Point, a beautiful bushy area. While Rita was away from school due to her long illness, Fort Street Boys' School was completed at Petersham. The gates of the old school went with them, and the historic fountain was moved nearer to the old building as roadwork encroached in preparation for Bradfield Highway and the Harbour Bridge.

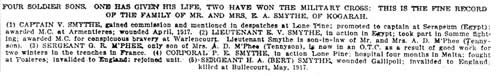

In August in the "Sun", photos of Annie and three other women had been published with a caption about the mothers of soldiers and the achievements of their sons. Annie received a letter from Thompson, their family dentist at Gladesville, eulogising over the achievements of the Smythe boys at the front.

A little later Clytie had a letter from Viv,

My Darling Sweetheart,

Was greatly pleased to get the cutting from the "Sun". Do you know, that cutting is the only photo I have in my possession now. You can make up for me if you like, a Xmas box of a pocket wallet containing photos of both families, and I can promise you, it will give me as much pleasure as anything bar being home with you again.

Vicissitudes

Several times Percy had a drink of rum to warm him and help him sleep. As a form of relaxation he sketched churches or ruins he had seen. He continued to write short stories and at last found a literary agency in Britain who accepted one and agreed to handle his work, for a fee.

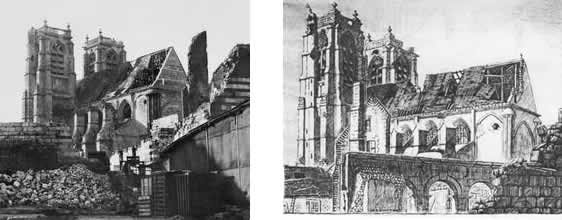

During this period Percy possibly first saw Corbie cathedral, which he later sketched. From memory he drew a sketch of Mt Comboyne, near Koppin Yarratt Creek, Australia.

After a period of fierce fighting, troops including the Smythe brothers were sent from the main front back to Flanders and others brought in to Picardy.

At Windsor Castle King George V decided to change his name from Saxe-Coburg by royal proclamation to the House of Windsor to remove the German connotation and sound more British.

During the year Percy also decided to change to Viv's battalion and succeeded in October. As with everything else he was conscientious and acted only after due consideration. Viv assured Percy he would get promoted again and could "put up a bar". Indeed he soon became a temporary corporal. It was already getting cold and there were overnight frosts, when they were returned to the Somme. The three brothers were again in this area and tried to see each other. Their cousins Ernie and Alf Graham were also nearby. When Vern was injured he went back to England. Many soldiers were given a week of riding lessons. Others did courses in climbing telegraph poles and repairing communication lines. At riding school he and two others had their photographs taken on horseback. Although Vern looked very assured and polished, he admitted that none of them could ride. Then he was assigned to the number one Command Depot in England. Vern got leave and went to Ireland to see his grandfather’s homelands and visit the family of Rene Hanna, Viola’s friend from Jerilderie, now nineteen and recently married. In Ireland the Hannas introduced Vern to Mary Hyndman, a cousin of Rene. Mary, in a pretty dress of blue and pink shot silk met Vern in a motorcar. He thought she looked a picture, which he would never forget.

Winter was approaching, water froze in the shell-holes, mud was frozen which made it easier for the men to walk on. Not long after, Percy contracted bronchitis. He was sent to the tent hospital near Amiens, then via Corbie to Rouen hospital and later to England, arriving just at Christmas. At last a "Blighty", but he was disappointed that his chance of further promotion would be reduced.

He sent cards to his brothers, his parents and to the widow Mrs Morgan. He had already been in correspondence with Mrs Morgan after the death of her son Percy on the Somme. Annie and Mrs Morgan were also writing to each other, and her address was used for mail as it was easier to keep changes up to date. After a couple of weeks in Birmingham hospital he was transferred nearer to London and Mrs Morgan invited him to visit. When he did so he found her to be young-looking, although grey and still very distressed over the loss of her son. Percy accepted invitations to see the sights of London and to go to the theatre.

Still instructing in England, Bert was now agitating to get back to the front as he felt he was not pulling his weight for the Motherland, but Percy thought that ranked as a "sjt mjr [he] was not doing too bad". Bert felt that his younger brothers were facing all the risks and winning recognition. His captain stated “He has always carried out his duties in a most capable and efficient manner, and I have much pleasure in recommending him as a suitable candidate for a commission”. This was more likely if he was with his own battalion. He was to be included in the next group but an outbreak of measles delayed this. He wrote “My guardian angel must be trying to protect me.” He wrote to his cousins at Myrrhee saying he was eager to get to France. He had heard that Uncle Robert had built a grand house at Myrrhee, and asked for a photo of it with the family.

On the next occasion when the Myrrhee Curries were all together they planned to get a photograph taken.

While at school young Bobby worked for his father. Having completed eighth grade he left school at the normal leaving age of fourteen, and had a dispute with his father. As they both had strong personalities and individual ideas they did not always see eye-to-eye. Bobby had grown some tobacco. When it was ready for sale his father had said, "There is only one boss here." The tobacco was sold and the money went into farm funds prompting Bobby to leave home. At first he took what he owned and went over the hill where he built a shack and grew millet; he also had sheep and sixteen beehives. Sometimes he went to the Evans house next door for dinner. It was suggested that he was calling on one of the Evans girls. He talked about ideas he wanted to try when he could go out on his own. After a while he went away to work for a sawmill.

Aunt Lyd, now over fifty, had received the £100 from her father's estate, which she had put into an interest-bearing deposit. This at last gave her some independence.

Ramsgate 1917

Ted and Annie

Ted and AnnieNow working in the city Ted had a habit of getting off the tram on the wrong side if it suited him; he also hated waiting for trams and would walk on to the next stop, even at the risk of having to rush when the tram came. Too much of his pay was spent on drink.

In order to invest in the Starr-Bowkett Society, the older boys had all contributed and continued to do so to meet the repayments. Annie was now able to put some of their allotments into an account for them and already had £80.

Viola, now a pretty young woman of twenty with big brown eyes and very fair wavy hair, had started dating a young man who had recently joined up. In her final year, now fifth year, at school Ida was, as always easily worried and upset. After her long absence due to illness, which had left her with a rheumatic heart, Rita had gone back to school but was quickly exhausted after any exercise and always felt tired and weak. At the end of primary school Eric had passed the entry exam and although he had not gained a bursary, had started at Fort Street Boys’ High School, which had been built at Petersham - a large three-storey building with arches along the balconies. He enjoyed it, especially French.

Gordon aged eleven said “I’m going to marry Nellie Potter when I grow up”. Because of her mother’s illness, Nellie aged twelve had had to leave school. Her two older sisters were not available to help, being married. There was an older brother Tom and three younger brothers.

France

That winter was the worst in European history. The mud was so deep that wounded men drowned in it. “Trench feet” was a major problem.

Vern and Mary

Vern and Mary

In February Vern went to Ireland to marry Mary J. Hanna Hyndman by special licence at "Trentagh House". Her family was very wealthy and owned five estates in the area. Mary's mother Margaret was a regal-looking woman. Mary went to the city and bought £300 worth of clothes and furs for her trousseau. At the wedding Mary had a bridal dress and veil (unlike Clytie). On the certificate it stated that Vern's father, Albert Edward Smythe was a "merchant" instead of "boot maker" and Mary's father George Hyndman was a "farmer". Among the wedding presents were paintings of Mt Mugish in Donegal near "Trentagh", the artist belonging to a local renowned art school. Vern's brothers were pleased to have another sister-in-law, especially such a pretty one.

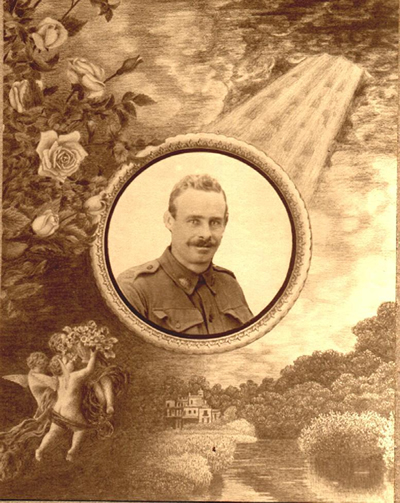

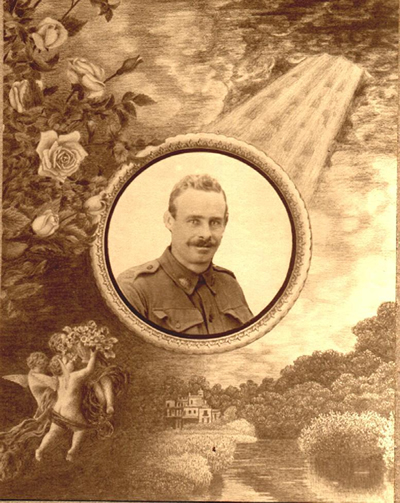

Finally in 1917 Bert was successful in getting back into the action. In doing so he reverted to the rank of corporal, but hoped to get promotion soon. Before leaving England he had his portrait taken to send home to his family and to Elsie Maloney. He had an enigmatic teasing half-smile, had grown a moustache and his hair was slightly wavy. He was twenty-seven. Expecting Elsie to send him a photo and write to him via Mrs Morgan he suggested she open the letter and look at the photograph before redirecting it.

There had been little movement in the war in the Somme area of the western front in over two years, although the Germans did withdraw in some places to previously strong defensive positions, known as the Hindenburg Line. It was a network of trenches, protected by barbed wire up to a hundred yards wide with many machine-gun posts and strong points, regarded as impregnable.

A beautiful and ancient tower in Coucy, France, was blown up by Germans in case it gave cover to the French Army. At the same time Russia began to crumble under the Revolution and eventually signed a truce with Germany.

According to his diary Bert left Amesbury at half past two at night on 13th March and arrived at Folkestone the next morning, embarked for Boulogne and arrived at Etaples by train. This was a base depot where men going from England to their units were "finished off" or prepared for the trenches. At first he had to undergo the "bullring" to get back into peak condition. It was an area about three miles [4.8km] from the camp where the men had to do circuits and various exercises. He was disgusted at having to do this. He was still a crack shot and believed he was fit.

SUNDAY 18th: Went to church this morning & heard a splendid & powerful sermon. The preacher was very good indeed - one of the best I've heard. Splendid news from the front. Our boys are pushing on fine.

MONDAY 19th: Went out and did a bit of shooting today. My rifle throws 1 inch left in 30 yds. In the afternoon went for a route march.

TUESDAY 20th: Bullring today with a vengeance. Had a very strenuous day of it, mostly Bayonet fighting. More good news from the front. Rec'd a letter from Mrs M [Morgan]

WEDNESDAY 21st: Wrote to E.M. [Elsie Maloney] Streak of rare luck this arvo, a letter from Elsie dated 31/12/16 the last one was 5/12/16 which came to light some considerable time ago. Funny how ones mail is messed about.

TUESDAY 22nd: No Bullring for me today as I've to go on guard this arvo. Had a lazy time of it during the day. Didnt leave my warm and comfy couch until brecker was nearly over. Rec'd one English letter during day from Brumm [Birmingham]. Was congratulated on the fact that I could not get to France for 3 months - & here Im in it the day it was written. Mounted guard at 5pm. Reproved cos my brass wasn't polished. (contrary to AIF orders, they want the brasswork polished in this joint, & even go to the extent of supplying the guard with a tin of Brasso) Congratulated on my pack. Only two "birds" [prisoners] in the Klink & they are fairly safe with a sentry on each of the four corners of the compound. [The Klink was a barbed wire open enclosure with a sentry at each corner so there is no great chance of any one escaping.]

FRIDAY 23rd: Dull day for the most part, but a little diversion introduced throu an officer on marching an armed party past the guard without saluting us, & the same officer on coming back gave the command "Eyes Right" instead of "Eyes Left" & then when the men looked away from the guard instead of towards us roared out "Dont be a lot of *-*-* fools cos Im one." Relieved about 5pm. Bed early - nowhere to go and no passes to go there.

SATURDAY 24th: Bullring this morning. Blarsted Company drill all the morning. The platoon officers rather shaky on their drill. Lewis gun lecture in the afternoon. Lecturing offr knows his job I suppose but he cant lecture. To bed early again, only place one can keep warm in. The mess is dopey - the dopiest Ive ever struck, no comforts of any sort. Tucker up to putty too. Stew stew stew - What's the use of worrying? P.E.S. [wrote to Percy]

SUNDAY 25th: Been having a glorious loaf during the day. Intended to write letters but had no writing paper & the canteens were closed to 5 pip emma [5pm], so I couldnt get any. Have been warned for guard tomorrow. By Jingo they are slinging it into me pretty hot. However guard is better than the Bullring. I can sleep in till 8 tomorrow. Laziness - Im the superessence of it. Have pratted my frame in for a pass to Etaples on Tuesday night. Have to be out by about 8. Guard doesnt finish till 5 so Ill have quite a long time in there. By Jingo the military is hot. They have the infernal hide to offer a miserable 5% leave to Etaples from after parade until 8pm which gives about three hours in town. Ill bet the gentlemen who made those restrictions go out oftener than once in 20 days & stay away longer than 3 hours. Went to bed very early - only place where one can keep warm.

THURSDAY 29th Have a nasty toothache - the blanky thing objected to me indulging in my passion for sweets. Mounted guard OK about 5. Four birds in the cage. Received a letter from Elsie dated early November. Altho it was plainly addressed to the 3rd, it had been all over the place but not to the 3rd. It was refused with thanks by the Sig Engrs [Signal Engineers] & the 22nd Bn; plastered all over it "NOT 22nd BN" - By Jingo no wonder ones mail doesnt turn up when letters plainly addressed to the 3rd go to the Sig Engrs & the 22nd.

FRIDAY 30th: Complimented by CO [Commanding Officer] on having the smartest & best turned out guard that had ever been mounted here. Warned that Im on draft leaving the following morning. Releived off guard 3.30 so that I could get equipped. Relieved so suddenly that I had no warning & so things were not as tidy as they might have been. Got straffed. Got everything fixed up to leave. Gee my pack is heavy. Ill dump something before I lump it many miles.

SATY 31st: Left early this morning. Pack too heavy to carry far. Loaded into luggage truck. Placed i/c [in charge of] rations with four men. Went through my pack & dumped my boot polishing gear. Couldnt dump anything else. Drank a tin of unsweetened milk. Train moved off about 8am Arr'd at some ungodly hole about 4.30 & after unloading rations joined my mob. Marched off for Albert an hour later & fixed up in tents. Got a bit wet marching. Coat and cape in my pack & didnt get a chance to get them out. Fixed up comfy for the night. Raining like H. Great if we were sleeping out.

In April there was a big offensive towards the German Hindenburg Line at Bullecourt north of Pozières. The Australians were to attack from the east, the British from the west. Viv was awarded a MC on 3rd April "for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He organised a strong patrol and maintained his position under very heavy fire until relieved. He set a splendid example of courage and determination throughout." The notification was sent to "Bonny Doon", Cleary St, Hamilton, Newcastle where Clytie was working at the time. Viv then headed further north. Bert was heading for the same district via a circuitous route

Bert's diary continues:

SUNDAY April 1st: Left Albert this morning & marched to the gas depot & then after being issued with a box respirator each & going through tear gas had dinner and Marched to this joint - Ribemont, some march too, arriving very tired about 4.30pm. Ribemont is a pretty big town with no apparent damage by Fritz. Big review tomorrow so I hear & the line on Tuesday. Have met quite a lot of old mates.

MONDAY 2nd: Big inspection of the Bde this mng by Divisional Cmdr. Marched out about two miles to do the job. Had the afternoon free to get ready to leave tomorrow. Got paid too & it came in very handy. Bought some sox 7 candles & something tasty to eat. Was told by RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] that Vernie had been killed, but do not place any credence on it as rumours are so unreliable. Possibly he is wounded.

Bert's surmise about Vern was correct. He had been wounded in the leg while fighting at Armentières, was sent to hospital and was able to go to Ireland to convalesce. Viv and Bert were now very close to each other.

TUESDAY 3rd: Saw Paul White & he saw Vernie two days previously so he must be OK. Moved off this morning & marched to Montaban [Montauban?] or some such place. rotten march too. Heavy pack and very sore heels. Arrived tired and put up in comfy tin huts. Can see the flares & gun flashes but can hear nothing as yet so must be a long way off. Am still a spare part with nothing to do except assist generally.

WEDNESDAY 4th: Oh we had a lovely march today 12½ mls to Fremincourt or some such name. Had my first good taste of mud & got a glimpse of debris & waste of the Somme battle. For a good way we moved on a track of duckboards laid over the mud, & then we had to plough our way through it. lovely. Beautiful. Saw a solitary tank on our way over. it snowed heavily most of the way, but our capes kept us fairly dry. Stopped in a little place for half an hour for dinner & then moved on to fremincourt. As we passed Bapaume on our right Fritz was dumping a few heavies into it. Got fixed up in billets such as they were after Fritzs work on them, & not satisfied with our quarters, a party of 7 of us scouted round and found a nice roomy place with a fireplace rigged up. Got it cleared up great & a lovely fire going, when some officer with a large party shoved us off. So we had to go back to our old place. Got a fire going & things as comfy as possible. One of my feet quite dry & the other was having a boot bath in a cup full of water. Changed my sox & burnt one of my boots quite hard trying to dry it. Fairly close to the line here.