Chapter 1

She sat in the boat with other passengers, her arm protectively around her six-year old daughter, and her eyes fixed anxiously on the people moving along the pier.

The skilled oarsmen pulled alongside the landing steps and stood with one foot in the boat and one on the steps as they helped the passengers. Magdalen Yabsley indicated to Jane by a slight pressure on her shoulder, when to move forward, until one of the men swung the slightly-built child into waiting arms. Her mother gathered her skirts in one hand and followed.

"Now my dear, here we are in New South Wales at last." Magdalen tried to sound matter-of-fact, as she gazed at the groups of people greeting, or waiting for friends and relatives.

"Where's Papa?" asked Jane.

"I can't see him. He may not have got my letter. He mightn't know we are coming. We must see now that we have all our luggage. Then we will start looking for Papa. Keep close to me. You don't want to get lost."

Magdalen, in her late twenties, with centre-parted hair, smoothed back and fastened into a low chignon, wore a plain bell-shaped brown dress with white embroidered collar and cuffs. Jane's dress was cut from a similar serviceable cloth and her hair was short and neat.

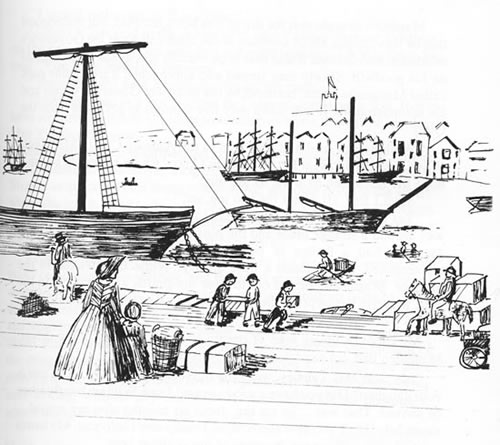

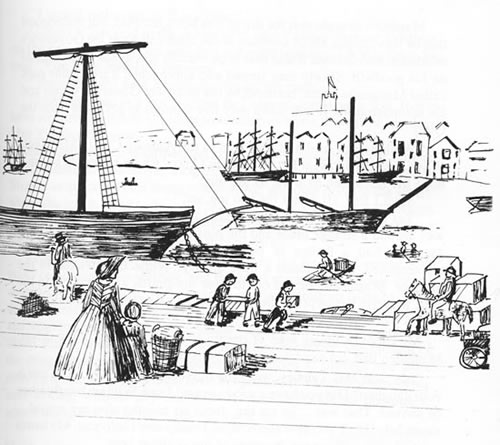

The luggage consisted of one small trunk and two large baskets. The two travellers waited and watched.

From the moment they had entered the harbour in the early dawn, Magdalen had closely observed every sign of life; a group of people on the little beach at Vaucluse had waved as they sailed by; sailormen, fishermen, labourers all paused and Magdalen noted that in general they were not unlike men of that type at home, on the other side of the world. They passed numberless arms and bays and after several miles had their first glimpse of Sydney Town, the spire of St James' church. They passed Pinchgut Island and approached Semi-circular Quay. Magdalen vaguely noted the fashionably dressed women, and that most of the men had substituted comfortable working clothes for fashion. The tenement buildings near the Quay had a familiar look. The windmills perched on high points were different; also strange was the smell of eucalypt trees. The shores were covered in native shrubs which were still green, although she believed that the season here was the end of winter. In the far background were sombre green forests.

The seasons were topsy-turvy she knew. They had left Plymouth in winter and it would now be summer. This was supposed to be winter in New South Wales, but the sky was bright blue, and workmen in their boats and on shore were only lightly clad. It was hard to fathom, but her thoughts were only superficially concerned with mixed-up seasons.

She kept telling herself that William was reliable and would not let her down. He would come to meet them. He must. But... it was over a year since he had written and many things happen in a year. Nagging thoughts made her uneasy. As they approached the Quay, some of her fears disappeared. Sydney Town appeared quite civilised. Many of the women on the wharf were dressed in precisely the fashion of the ladies in Plymouth, and the officials who examined her papers could have been the same ones who had helped her to embark. After some of the ports they had see on the six-month voyage, it was almost like being home again. The crowd on the wharf soon dispersed.

"Where will we look?" Jane was asking.

"We'll go to Uncle Gilbert to see if he knows where Papa is and why he isn't here," Magdalen tried not to let her small daughter sense any of her anxiety.

"Where does Uncle Gilbert live?"

"Uncle Gilbert is the Aide-de-Camp to the Governor, so I expect he has quarters near the Governor's House." She had explained this to Jane before, but the child had not accepted the possibility that Papa would not be there to meet them. Visiting a complete stranger, even a relative of Papa's, was not a pleasant prospect, but when that stranger belonged to a completely different class, the prospect was daunting indeed.

Magdalen braced herself, mustered her courage and ordered an open carriage to take them and their luggage to Government House. Many of the buildings were lofty, some would do credit to the best areas of Plymouth. Soon the castellated turrets of the Governor's stables came in sight. She noticed that the turrets and tall chimneys of Government House were still incomplete.

"That will be the new Government 'Ouse," the driver pointed out.

"This is the temporary 'ouse. I hope you don't 'ave a letter of introduction to the Governor. I'm told he doesn't take too kindly to people with introductions. He's been pestered by them."

Magdalen thought the driver was being familiar, but understood that he was curious about a woman of her class calling at the Governor's residence, and decided it was best to be friendly too, as she must depend on his goodwill. Slowly they turned and approached a triangular park called Macquarie Place, borded by the houses of Governor Gipps and his administrators. It had taken only five minutes to get there from the Quay.

Governor Gipps

Governor Gipps"Well, no; my husband is related to the Aide-de-Camp, Mr Elliot. When my husband sent for me he didn't know where he would be, so I hope Mr Elliot can help me locate him."

"Shall I find Mr Elliot for you ma'am?"

"Yes please," said Magdalen, glad to be spared the need to find her way around a strange place and the possibility of making social errors. She still had a feeling of being on board ship and was a little discomposed, her stomach a little uneasy. While they waited in the carriage, Magdalen pointed out to Jane the guards and convicts in the area. Much to her surprise, the Quay and their ship lying at anchor, were only a block away.

Mr Elliot, a young man of twenty-two, came out with the driver. Magdalen had not expected him to be so young.

"My dear Mrs Yabsley, welcome to New South Wales. And this is your daughter? Did you have a good voyage? I saw William briefly when he arrived. That was... let me see, about six months after my arrival... about July '38. Two years ago now, so I really can't help you. My hands are tied, you understand because of my position here."

Magdalen did not understand. She realised there was a mystery and was dismayed. "When he wrote he said he was timber-getting, but didn't say where."

"He could be anywhere within the Nineteen Counties, or he could even had gone beyond, though of course that is discouraged. There is talk of a Big River up north, beyond the Settled Area. Hasn't William an aunt on his father's side? She could probably help you more than I could. Do you want to stay in the town for a day or two? I can find you some suitable lodgings."

"They live at a place called Myrtle Creek near Stonequarry. How long would it take me to get to them?"

"Stonequarry is to be renamed Picton. It is on the road to Yass, about fifty miles away. The journey takes all day. The coach will be leaving shortly."

"I would rather go on if possible."

Gilbert Elliot said to the driver "Put Mrs Yabsley and her daughter on the coach to Yass. See that they are comfortable." To Magdalen he said "You have money I presume."

"Enough," she said hoping she spoke the truth.

"I am required in a few minutes so I cannot accompany you. If you have any problems don't hesitate to contact me again. Goodbye, my dear Mrs Yabsley for now."

Magdalen was so disappointed she hardly noticed his slight tone of condescension. The driver took them across the bridge over the Tank Stream as quickly as his horse would move, and then down to the wharf, where the coach was nearly ready to leave. The box seats were filled with gentlemen and so were several places inside. Magdalen and Jane entered the coach and their luggage was stowed away.

Progress was slow until they had passed the Barrack Ground with many red-coats in the vicinity, and the Market area where drays waited among sheds and stalls. Jane, exhausted after getting up early to go on deck with her mother as they sailed up the harbour, now curled herself up and went to sleep. Magdalen no longer had to put on a brave front. Her throat aching with unshed tears, she felt quite dispirited. She thought of the things that could have happened to William to prevent him from meeting them. She took the letter from her pocket. It was only a page in his neat writing, without any unnecessary word, as were all his letters, addressed to her as Marley, his pet name for her.

September 1839

My dear Marley,

You should have got my letter about our arrival in Sydney Town after charting the north-west coast of the country. There was a letter from you waiting for me when I arrived, but I have not had a letter since, as I have left the 'Beagle', and am working in the wilderness, timber-getting. I am earning good money and I know I could make a good life for us here. There is work for all and reward for hard work. In this climate people live well without a lot of worldly goods.

I cannot give you an address, but you can write to me at Sydney Post Office as before. Let me know your plans. Jane would love it here, the climate is so healthy for children. Give her my love.

Love from William

Magdalen thought of the damp basement room where they had lived in Plymouth, and of the three babies who had died there. William did not even know about the third baby, a girl, who had been born several months after her father had left on the 'Beagle', three years ago, and who had died a fortnight later. Before that, Baby William had lived for just a month, and Baby Harriet for only a day. Even now she could not bear to think about the despair she had felt trying to care for the ailing babies. Her mother had said "it is the will of God. He has taken them out of their misery." Women were forbidden to grieve, and people might seem callous but it was part of life.

HMS Beagle

For a moment she was back in that cold room, at No 4, George's Lane, reading William's letter. In New South Wales it would be warm and they would not be hungry. There was plenty of land. She had pictured herself gathering vegetables and fruit from their garden and fresh eggs from the chickens. Jane would never have to work in the factories in Plymouth as child labour. She would marry someone who had made his fortune and she would never know the hopelessness that her parents had felt.

As soon as Magdalen had received William's letter, she had replied that she would be on the next ship. Her answer went on a ship sailing the same week, but she knew it was possible that William may not get it before her arrival. The ship carrying it could be delayed or even wrecked. She and Jane left only weeks later. And after six months there they were, riding along dusty, rutted roads of Sydney Town. The tiny huts with grubby children playing in the dirt, looked incongruous next to large brick and stuccoed business houses. The blinds of the coach were drawn against the dust but there were glimpses of buildings for a couple of miles, then the forests and farms. Her eyes looked at her fellow travellers, but she could think of nothing but finding her husband in this enormous frightening country... that is if he were still alive. She dismissed the thought. Time enough to worry about that when she had found his relatives, who should at least have more recent news. Maybe he was quite near at hand, but had not received her letter. Maybe Aunt Ann...

Jane began to stir. Magdalen took a deep breath.

"Are we finding Papa?" persisted Jane.

Magdalen shook off her apprehension. There was only a hint of a tremble in her voice as she answered. "We'll find out this evening, my dear."

* * *

Towards evening the coachmen slowed his horses.

"Here we are ma'am, the farm you wanted. What name were you looking for?"

"For Mr and Mrs William Sawyer, my husband's aunt and uncle."

The driver spoke to the farmer who studied them and the travelling baskets which the coachmen was handing down. When William Sawyer, a man in his forties with the beard of an ex-soldier, had taken it all in, he called to his wife.

"Ann, come quickly. Here is William's wife and daughter."

"You're not serious?"

"Indeed I am."

"You poor dears," cried Ann Sawyer bustling out.

"Come in and rest while I get you a bite to eat. The little one must be famished. Poor child."

"Can you tell me where I can find my husband?"

"No, I'm afraid that we cannot. You must stay with us 'ere for a while. My husband will see to the luggage and I'll stir up the fire for tea."

Unsteadily Magdalen and Jane walked towards the little farm house, their clothes now a dustier shade of brown, their spirits very low. They brushed the dust from their clothes and shook the handkerchiefs they had held up to their noses. The coach went off in a cloud of dust.

"Do you know if my husband has got my letter? We sailed only a few weeks after I sent it, so he may not know we are coming."

"Sit down, my dear, sit down. William left Sydney Town two years ago. Before we came to Myrtle Creek from Kent Street. We have not seen him since."

William Sawyer came in with the trunk. "Magdalen must have enormous faith in her husband to come so far alone. Have you any idea what it's like 'ere?" there was a note of misgiving in his voice, but he accepted that it was the proper order of things for women to follow their men.

"Only tales I've heard second-hand. I half expected to find nothing but Blacks and convicts and kangaroos, but the town looked really quite civilised. I was surprised to see an emporium. I didn't expect to see such a large establishment... and next to a wattle-and daub hut!"

Eight-year old Susannah came in from play, with three younger children, and they all crowded around Jane who sat silent and embarrassed. Aunt Ann soon had the fire blazing.

"Did my husband give any indication of where he was going?" asked Magdalen.

Uncle William answered "He knew a man from his ship, H.M.S. Beagle who told him about timber getting up north. His name was Robert? No Richard Payne. He lived near Parramatta. Perhaps we cold contact him. I could ride over next week."

* * *

A week later Uncle William brought back news that Richard Payne had met a man Richard Craig, who was working as a sawyer at Small's timber-yard at Kissing Point, near Parramatta. This man, Richard Craig had escaped from hard labour in chains at Moreton Bay and had lived for six years with the Aborigines in uncharted country in northern New South Wales. While working at Small's timber-yard where they were building a small vessel, he had suggested that it would be a good idea to embark her in the timber trade to cut cedar in unlocated Crown Lands he had seen in his wanderings with the Aborigines. He described magnificent cedar trees growing on the banks of a 'Big River'. About two years ago they had taken the vessel the 'Susan' and set sail for the 'Big River' with twelve pairs of cedar-cutters. That was just before William Yabsley had arrived with Richard Payne on the 'Beagle'. William Yabsley had been most interested.

"Richard Payne thinks that we should ask the captains of ships trading on the north coast, for news of 'Susan' and the sawyers, and through them get news of William."

"His trade is timber of course." Magdalen was talking half to herself.

"That's probably where he is."

"You'd be surprised at how much timber is used in the colony. Nearly everything is made of wood. All the good timber for fifty miles of Sydney Town has been cut. It's the Red Cedar they're so excited about. Huge trees. The wood easy to 'andle, but very strong. Timber-getters make a fortune."

"I can see William now," said Magdalen. "He would be in his element. He is so determined when he makes up his mind. Exceptionally strong for his size."

"Mm, not very tall, but full of idealism. We have a great admiration for 'im and believe he will go far."

"He seems to have gone far already. I'm sure he's in this great timber country. What did you call the district? And why didn't he tell you?"

"There could have been trouble about him leaving the ship. Mr Payne called it the 'Big River'. It's officially outside the limits of settlement."

"How can I get there?"

"Patience, my dear," begged Aunt Ann. "As soon as we can we'll start making enquiries for you. You couldn't possibly go after him unless you were certain of where 'e is. And if he's up on this Big River it would not be wise. Do you realise what life is like away from Sydney Town? The Blacks can be a problem, and some of the men are escaped convicts, villains who have something to 'ide. Fugitives from the Law. Very rough. Absolutely impossible for a respectable woman and child."

Aunt Ann had made tea and was pouring it into mugs for the adults. Susannah poured milk for the children, and Jane drank thirstily.

"More?" asked Susannah.

Jane looked at her mother for approval.

Uncle William spoke. "There's plenty of milk. The child needs building up. Give 'er some more."

Magdalen was restless. Her host and hostess were very busy, and their two-roomed cottage was very crowded, so after a few days Magdalen went back to Sydney Town by coach, and sought the ships coming from the north. She had told Aunt Ann she was going to the Post Office to collect William's mail, which included her own letter to him. There was nothing for her. Then she made enquires about shipping.

"Coastal shipping uses the Market Wharf. Go back past the Barracks until you come to the Market, then turn right."

Feeling very conspicuous walking around the streets alone, Magdalen followed the directions. Before she arrived she was beginning to overcome this feeling. If people stared, she ignored them.

Large numbers of market boats were unloading produce form the Parramatta and Lane Cove Rivers. Timber in great quantities was stacked along the Quay. After many enquires, she met Captain Freeburn, who was trading in the north.

"I was a crew-member on the 'Susan' when she entered Big River. I now trade there regularly. There are two main cedar camps at the depot, and also a number of other sawyers on the river. The Governor had called it the Clarence, I believe."

"I have recently come from England to join my husband, William Yabsley. Do you know him?"

"I'm sure I've heard the name somewhere. What does he look like?"

"Not very tall. Nuggety build. Fair hair. Plymouth accent. A serious sort of man."

"Yes I think I know him. Had he trained as a shipwright?"

"That's him for certain. Could you take me to him?"

"Indeed I could ma'am, but do you know what you're saying? It's some hundreds of miles north. Beyond the Nineteen Countries. Beyond the Law. It's a man's country. There are no women except for one or two who went with their men. You have not been in the country long enough to know anything of the hardships. Only one kind of woman ventures out alone."

"If my husband is there it is the place for me. When are you sailing?"

"Early next week. But this man may not be your husband. Let me enquire on this trip and I'll send you word when I would be going there again, in a month or so."

"I believe it is my husband. There are no two men like him."

The Sawyers tried to dissuade her, but could see that if William were an exceptional man, then his wife was equally exceptional. They persuaded her to leave Jane with them, expecting that she might come back again on the same ship. Aunt Ann gave her food for the journey. Uncle William gave her some seeds, and instructions for planting and care, more to show his moral support than because he believed she would settle in the wilderness.

"Goodbye Jane my dear. I will be back for you as soon as I can. Be good for Aunt Ann and have a good time with the children."

"That's just like William," said Aunt Ann as Magdalen was leaving.

"Sending for 'er and taking it for granted that she will find 'im."

"If he's really still alive," said her husband ruefully.

"He is. And she will find 'im. Come along Jane. You'll soon see your Papa again," said Aunt Ann a trifle too confidently.

NEXT >>

HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle