Chapter 27

The years were rolling by. The heat of summer was followed by days and weeks of rain, the cooler winter months that merged into spring and humid summer again. Magdalen felt herself to be more of an onlooker than a participant in events these days. The house contained every labour-saving device and as well she had plenty of household help. The events in her life were the arrivals of the grandchildren. When they came to visit Magdalen made the most of being a grandmother and of having time to rock her grandchildren on her knee, to tell them stories and to listen to their chatter. And as she did so she wondered how Jane was coping with her brood of girls. Jane of course would be well-organised and knew how to manage open fires and other aspects of bush life, but how much time did she have to enjoy her family? Whenever Jane wrote that she was expecting another baby, Magdalen hoped desperately that she would have a son but each time it was another daughter. After Emma and Ann and Frances came Mary Jane and Rosa.

No word had come for a long time and Magdalen waited anxiously tor a letter. When finally it came it told of their move to their selection on the Bellinger River. They had gone by dray to Port Macquarie and boarded a vessel bound for the northern rivers. Their whaleboat was launched at Bellinger Heads as the shifting nature of the bar at the mouth of the river made it impossible for coastal shipping to come into the river. William took the oars to row his family up-river with provisions for several months - Mary nursing the baby, Jane holding the toddler, the three girls sitting patiently together. When the ship had anchored near the heads, the Aborigines sent smoke signals. Some settlers soon came down the river in their boats and explained that they had an arrangement with the Aborigines to signal when supply ships arrived at the heads. Otherwise the settlers had to walk to Kempsey and carry their provisions back in packs.

The block they had selected was on a bend of the river several miles up, on the high bank, opposite a sandy beach. There were seven ferns near their selection which gave the district its name, Fernmount. There were a number of settlers further along the river at Never Never and Boat Harbour. The river was called Billinger or Bellinger 'clear water and cool springs'. There was excellent timber to be cut and fertile farming land once it was cleared. The men who had met them at the heads lived down-river but had come with them to help them pitch their tent and get organised. Jane immediately fell in love with their new home and the next day sat down and wrote to tell her mother to tell her about it hoping to be able to send the letter when one of the settlers went to Kempsey for supplies. In fact her next letter went soon after the first. By then they had plans to build a store, a three storey building on the river bank with the bottom floor above the wharf from which produce could be unloaded directly from the ships which came up-river as far as Fernmount when they could cross the bar. The top floor of the building would be level with the road for the convenience of customers. They had begun a good home on top of the hill, above the seven ferns. William found plenty of work. A wide variety of crops was tried experimentally - cotton, sugar, fruit trees, ginger, corn, coffee, silkworms. Bananas were found to get bunchytop disease. The main problem they had to contend with was the treacherous shifting sandbank at the bar. The people suggested without much confidence that the Government should do something about it.

The blocks on either side of them were owned by a family called Marx who had come from Germany. Freda Marx had married Alex McLennon, the first marriage on the river, and Freda had become the local mid-wife. Her brother James showed an interest in Jane's eldest daughter Mary, who was also eager to get married. How the years passed thought Magdalen. Little Mary who had been a child of twelve when they left Coraki, wanting to get married!

* * *

Frances and William called nearly every Sunday for a visit and to attend church bringing their three little ones, Arthur, Louisa and Alice. A church had been built near the large fig tree under which the congregation had been meeting for services. The church was built of poles cut in the bush and hewn slabs for walls and tea-tree bark roof and planking for seating. A new cottage had been built for Reverend Thom and the old 'Manse' had become a ferryman's hut.

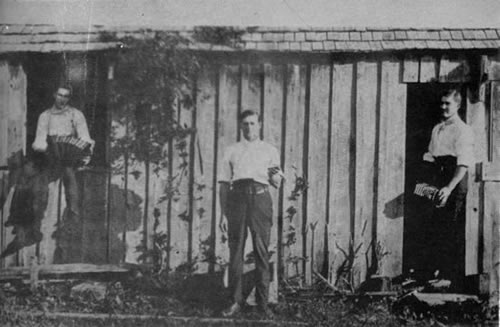

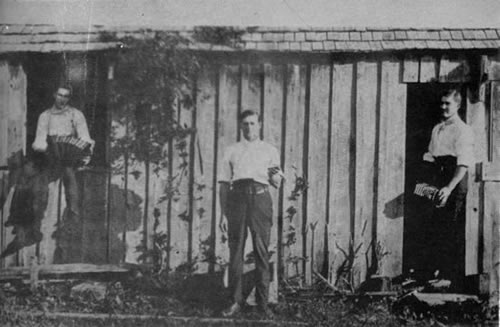

Accommodation for employees at the saw-mill. It had previously been built for apprentices at the shipyard and was called the "Boys' hut"

(by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)

After church the family had dinner together. Frances told about the progress that had been made on their cottage at 'Repentance', where the house had been lined and William had made a horse paddock, a garden, stockyard, a shute for firewood. Magdalen thought Frances did not look well after the birth of Baby Alice Elizabeth, so she gave her a jar of her favourite recipe for good health, a mixture of dates, dried figs, mixed fruit, ground senna and paraffin.

"Take one teaspoon every night to build up your strength," she advised. Magdalen had put on weight steadily over the years, and to her Frances who was rather tiny, looked quite frail and undernourished. Frances and the younger girls, Annie, young Magdalen and Lizzie talked about fashion and were all very conscious of what was worn in the city. Their mother was unaware of fashion and knew that she did not have what they called 'good taste' or 'an eye for fashion'. So she left most of the choice of clothes to them. The styles were graceful with full skirts over crinolines, but to a woman used to chopping wood, lighting open fires, carrying water from a river, they were cumbersome and she was not able to get used to them. The younger girls had given away Magdalen's practical and well-worn clothes to the Aborigines, so that she would not be tempted to wear them.

Eliza and John Robinson with five little ones came only occasionally from Swan Bay. John junior had been followed by Elizabeth, Eliza, Harry and Maria, now a toddler, with another one on the way. When Eliza managed to make the journey she said "I never realised how fond children are of a grandmother. They talk about you all the time."

* * *

The 'Coraki' and the 'Schoolboy' traded steadily but William was far from content with the state of his affairs. His next ship would be even bigger than the 'Schoolboy' and he intended to build a ship-shed to house everything under one roof, tools and equipment, plans and sails, as well as the vessel which would be 260 tons. As with all his enterprises he gave it a lot of thought before anything was said. The daily work went on with only minor set-backs from illness. Magdalen wished he would relax. It seemed impossible that he could continue indefinitely without great risk to his health and their livelihood.

A year after her launching the 'Schoolboy' ran onto the bar at Ballina, but was refloated the next day. Where were the improvements they had been promised?

William began to build his Ship Shed down-river from Coraki Cottage. It was unlike anything in the Colony, he was told. First he had chosen ten enormous posts, each forty feet long and weighing five tons. Holes ten feet deep were dug along the sides of the site which was a hundred and fifty by fifty feet On top of these posts a floor would be built with a loft which was to be twelve feet to the apex, with no partitions or pillars to hamper the laying out of the canvas for the huge sails. Charley was sent to measure trees, having to walk for miles up and down slippery hills in the rain through thick scrub. The posts were hoisted into position with the aid of sheerlegs, tackle and bullocks. While work progressed steadily on the huge shed, the other commitments could not be neglected.

The apprentice-boys' house at Coraki was shingled and other improvements made, and a punt built for the crossing. The 'Schoolboy' had proved to be a very fast vessel as William had predicted. She held the record for a sailing vessel, Melbourne to the Richmond River in four days. They set all sail and never touched a reef until they reached the Richmond River bar. Then they waited for three weeks for suitable weather to cross in. On one occasion the 'Schoolboy' and the steamer 'Waimea' crossed out on the same day. A strong easterly gale blew up and lasted for three days. The captain of the 'Waimea' went below and got drunk in despair, leaving the crew to manage as best they could. They were blown off course and arrived in Sydney three days after the 'Schoolboy'. On another occasion the 'Schoolboy' raced with the 'Lookout' to Melbourne and lost by only two hours.

The mate of the 'Schoolboy', Mr Hanson, had painted a picture of the ship in Bass Strait, and had presented it to Magdalen. It was a combination of pen drawing with touches of blue water-colour. Magdalen was very touched by the gesture and gave it pride of place in her drawing room, showing it to all visitors.

Barque "Schoolboy"

As had been the custom, a regatta was held every year at Coraki, organised by John Yabsley. There were skiffs, no outriggers, all built on the river. John had built several of them, others had been built under William's direction. Contestants rowed around two boats anchored in the river a mile apart. The onlookers took up positions from where they could see the whole race. It was always a picnic day for the district, in the tradition established soon after John's arrival. There were also horse-races around the Coraki course which William kept in excellent condition although he was not interested in racing personally. William junior maintained his interest in horses and racing but of course had long ago grown too big to be a jockey and had given up that youthful ambition. The young people often went to Casino to horse-races and to cricket matches and stayed with James Stocks the chemist The young people thought nothing of rowing many miles for a match. From time to time the Lismore team rowed seventy miles each way.

On these occasions the teams assembled on the field about ten am in their ordinary casual dress. They removed their coats and vests and boots, and rolled their trousers up to the knee. They believed they could run faster bare-foot, providing they did not come across any prickles or stones. A batsman who kept his boots on was considered a tenderfoot and a drag on the team.

Young Tommy, now fifteen showed great promise as an all-rounder. Playing in a match at Gundurimba he hit a ball into a parrot's nest in a hollow of a tree and killed the parrot. Tom added several runs to his score while the teams argued about getting the ball down again. At last an Aborigine was engaged as tree-climber. When he threw the ball down a fieldsman caught it and appealed to the umpire who gave Tom out.

During the other team's innings a ball was hit into the river and Tom who was fielding near the boundary, gave half a crown to an Aborigine to swim for it. This caused more argument about rules and fair play, and eventually the boy was appointed swimmer for both sides.

Towards the end of the match a hotel window was smashed and the publican yelled across the field.

"Now you'll have to appoint a bloomin' glazier for both sides."

By this time Harry was an experienced cricketer, and was considered one of the mainstays of the Coraki team, and it seemed to have changed him, to find something he really liked and was good at. He showed no interest in young ladies but happily took his sister Annie with him. Annie was most keen to go to all social events, especially if there was dancing. She was never short of partners and rarely sat out a dance all night. These two members of the Yabsley family, both in their twenties, seemed in no hurry to get married.

Magdalen worried about her two middle children more than about the others. The older ones had settled down to good marriages. The younger ones had excellent prospects, and none of them seemed to have any real problems. But Annie and Harry sometimes seemed to be chasing rainbows. Their future happiness apparently depended on success at cricket and taking part in local social events. If only she had had more time with them when they were little, she felt she would be closer to them now and able to talk to them more freely.

While the young people entertained each other, the adults talked about events of the day. In the 1866 election Alex Mackellar had been a candidate representing the squatters' interests, but he was defeated by Jack Robertson, 'The settler's friend', who it was hoped would achieve something for the district although he had made violent attacks on the local squatters. Many selectors had doubts as he had already been instrumental in passing the Land Act which brought hundreds of settlers to the river and resulted in much conflict and resentment and hardship to all parties. As it eventuated Jack Robertson had become Premier during his term of office and did little for the settlers. His main ambition seemed to be to quash every privilege and petition of the graziers, including the bridge at Casino. Petitions continued for the bridge and a telegraph line for Casino and Ballina, the people felt very much neglected. Doctor Dunmore Lang kept alive the issue of annexation to Queensland, or failing that, the formation of another new state.

These issues seemed rather remote to most people on the river although they were hotly debated. More immediate was the problem of pleuro-pneumonia which still raged and many graziers had to sell their stations and move to new areas further north and west.

An event which pleased the villagers at Coraki was the wedding of Bill Yeager who still had an attractive Canadian accent, to Mary Ann Webster. Reverend Thom performed the ceremony in the little bush church and everybody joined in the celebration, partly because Bill was so well liked and partly because no such occasion was ever allowed to pass without taking the opportunity for a social gathering. A photographer was hired for the occasion and while he was at Coraki Magdalen arranged for a photograph of Coraki Cottage. She and the girls dressed in their best crinolines for the wedding, Annie, Magdalen junior and Lizzie Yabsley, Frances and little Arthur and Louisa, and Frances' sister Louisa who was visiting. Magdalen senior felt she might not be able to stand still as long as required, so the photographer brought her a chair to sit on. The others spread out on the lawn and made an elegant picture. The men could not be persuaded to join them although they readily joined the social activities.

Coraki Cottage from left Magdalen, Frances holding Louisa, Arthur, Frances' sister Louisa, Magdalen junior, and Lizzie.

(by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)

Henry Barnes was also visiting. He was so glad of Magdalen and William's present prosperity and told them about his home at 'Dyraaba', rather a rambling home with a big garden.

"You should see it, frangipani, jasmine, Bunya trees, pines, silky oaks, jacarandas. Grace does most of the organisation, she's a very keen gardener. The garden grows and the family grows, our latest child is Walter Clarence. But business is slack. Nothing will sell except at a sacrifice. I wish we were only out of debt. Stud cattle need chopped lucerne, ground and sifted maize, bran, ground pumpkin and some salt, all well mixed together. It seems there is nothing but expense and no income."

"It will come out all right you'll see," Magdalen tried to cheer him. It was unusual for Henry to be despondent. She teased him a bit about stories she had heard of him taking his daughters' part against their Victorian mother, telling them dubious stories and leading them astray.

"I don't lead them, they lead me," he assured her. "Is Jane still without a son? Any more daughters?"

"Jane's latest daughter is Grace. They are very proud of the sugar they are making, the palest on the river. Fernmount is expanding rapidly so she says, although the police station and court-house for the district will for some inexplicable reason be built at Boat Harbour. The people at Boat Harbour are pressing for the name to be changed to Bellingen, they expect to be the main village although Fernmount has been until now. Jane loves it."

"I'm glad she's happy. I'm glad you're doing well here."

"William has been able to employ many men who had been looking for work. We're progressing steadily. I wonder if it can last."

"There are a lot of problems for a lot of people. The Queensland government used borrowed money for public works and has gone bankrupt. Such a young state and already in trouble. But of course they can't help the economic deflation, and it is usual for the government to use surplus labour for roads and railways. I wish I hadn't borrowed so much."

"William has always been against getting into debt, especially in the early days. By the way I don't suppose you've seen his latest invention. I'll get one of the children to show you while I make some tea."

William had devised a novel means of breaking in bullocks. He had built a yard with a double fence, forming a lane just wide enough for two yoked bullocks to walk around. The inner fence of the lane was only three feet high, so that the teamster could lean over to yoke up, out of reach of bullock horns or heels. Two well-broken leaders stood at the head of the lane and behind them was the yoke ready for the unbroken bullocks which entered by a gate and rushed for the other two bullocks. When they got close the yoke was fitted over their necks and once in a team they had to go. They followed the trained leaders round the lane until they too were well broken. This, William told all visitors, was also an effective way of arranging a long team in good order for a start. Everyone who came to look was invariably impressed with the whole system of well-planned cattle yards. Henry was impressed but not surprised.

The number of cattle now approached one thousand, but that was a minor part of William's world. The Ship Shed was going up slowly, the ships came in regularly, ship-repairs were frequent, the store and timber-trading demanded time and energy. William told Henry he had also become a banker and credit manager for the sawyers with whom he traded.

"Magdalen has more help now and less to do since the children are growing up, but you seem to be busier than ever."

"I can't afford to sit back now. I've lost a lot of land around the house and shipyard when the village of Coraki was laid out, but I've taken up selections for myself and the boys nearby and you know what that means."

"In one way it's good to have the village so close, it will bring a lot of trade to your store. As it's on such a strategic spot on the river, I'm sure the village will go ahead steadily since the auction sale of land."

"Everyone still has to use the river and go past my door."

"Yes it's quite a tortuous route, but I much prefer it to the tracks which are mud, slush, scrub and grass as high as the saddle."

"Do you know I've called a meeting to get a Provisional School for the village? We'll hold a public meeting in the church."

"I'm glad to hear it," said Henry. "It's something you've talked about for a long time."

William's belief in education was as fervent as ever. He was sure that his good fortune in having been educated had played a large part in his success. Provisional or part-time schools were opened in many isolated parts of the Richmond River. An allowance of £45 was made by the Council of Education for the buildings and furniture and £60 a year for the teacher's salary. When William called the public meeting, making use of the new slab church as a meeting hall, he explained the procedure to the settlers who strongly supported him in applying for a school.

"If the application is successful, I will build a school Coraki can be proud of," he promised.

Shortly afterwards, Eliza's toddler Maria died at Swan Bay and for the first time in her life Eliza had to face a tragedy. To everyone's surprise she adjusted to the loss of the little one within a comparatively short time. Having sat by the baby's bedside and done everything possible to make her comfortable, she had blamed herself at first, but was soon able to come to terms with her death and was able to look forward to her next baby, due in January. Maria Robinson was one of the first to be buried at Coraki Burying Ground out near the Blacks Camp. William personally fenced the grave and gave it a coat of paint which he mixed. In August when Frances gave birth to her fourth baby, she called her Maria. Eliza called her next baby Maria also.

* * *

Meanwhile the Ship Shed was being shingled with 50,000 blood wood shingles and plans were being made to sell the 'Coraki' and build an even larger ship. Word came from the Council of Education and a start was made on the schoolhouse straight away. Thomas King did most of the carpentry work. In his spare time William was indulging in his favourite hobby of boot-making. He saw to it that Magdalen never had to wear shabby shoes again; even though her footwear might not be the latest fashion it was always comfortable and strong.

"Whatever he does is certainly meant to last, whether it's shoes or sheds over the saw-pits. Even the sheds over the timber awaiting shipment are strong and well designed. And the school will be the best in the district."

"He won't accept anything but the very best," agreed Thomas King, now one of the trusted workmen. "He made sure that we all learnt to do things properly when I was apprenticed. Nothing shoddy."

"It's still like that," said Oliver Jones who in his spare time was learning to do fine in-laid work under William's guidance. "It amazes me how he knows so much about everything and keeps an eye on everything around the place."

Magdalen agreed. She knew that Thomas King was now one of the few men that William felt he could really depend on to carry out tasks to his employer's satisfaction without strict supervision. And Oliver Jones showed great promise at sixteen. They expected that Thomas would marry young Magdalen in time and it also seemed that Lizzie showed a lot of interest in Oliver. Lizzie at sixteen had the task of keeping a diary of events on the property and even that had to be done in her finest penmanship. In many ways Elizabeth or Lizzie as everyone called her was much like Eliza, being full of enthusiasm, very outgoing and pretty and always managed to persuade her father to do what she wanted.

"Papa," she asked "When you put the floor in the loft of the Ship Shed, I would love to have a party. I'm sure you can make the flooring smooth enough for dancing, can't you?"

William's plan to use the loft for drafting plans and sail-making were of secondary importance. She and young Magdalen and Annie were full of ideas to make good use of the large area. It was Lizzie the youngest who had the determination and perseverance to plan an enterprise and solve one at a time, any problems involved in its execution. It was she who saw to it that the two inch thick pit-sawn timber flooring was to her satisfaction.

Although there was still a desperate shortage of girls, Lizzie felt no pressure to get married. Magdalen thought about Jane who at sixteen had married Fred West. On the contrary, Lizzie looked forward to some years of accepting whatever invitations appealed to her. The world was at her feet since the dramatic change in her father's status and the progress which had been made in the district. They could now travel around more to local events and there was a continuous stream of callers at Coraki Cottage so the younger girls had no lack of admirers. But no matter what invitations they accepted, Lizzie and young Magdalen let it be understood that Oliver Jones and Thomas King were their favourites.

They had witnessed many changes. At first there had only been the timber. Then sheep had been introduced, but the climate had proved unsuitable and they had given way to cattle. Now agriculture was being introduced. Corn was found by the selectors to be very uncertain; sugar cane gave hope. The Sons of Temperance which had formed groups in Casino, Lismore and Ballina, wrote to the Agricultural Association for information about sugar cane. William Clement urged James Stocks to call a meeting of prospective planters at Casino, and also sent samples of his cane to C.S.R. for exhibition and report. Maize farmers did not understand cane growing and had many problems. They tried to crush cane in improvised mills, between horizontal or vertical rollers drawn by bullocks or horses revolving as on a treadmill. The juice was drawn off, boiled and skimmed off, boiled again and left to granulate. About 40% of the juice could be extracted. The first sugar mill was built at Codrington, a few miles up-river from Coraki, by John McKinnon.

The schoolroom was finished, a beautiful building of cedar. The women helped prepare the schoolroom and schoolhouse for the arrival of the first teacher. A country schoolmaster was quite a new figure in the local society, asserting his authority with a cane and a punishment book. The first teacher was Mr Arthur Small, who arrived just as Charley and Tommy started out to haul the keel for the new ship the 'Examiner' which was cut near Tatham. They would not benefit from the school, but some of the apprentice boys and other children from the village were enrolled. Until then education had depended on the squatters' wives or anyone else with a little learning, who could instruct the children in between chores. The children at Coraki school would undoubtedly be called upon by their parents to help with tasks before and after school, and at busy times during the day as well, but on the whole they would have much more regular education than their parents. Some of the girls would even be able to learn music and other desirable feminine accomplishments.

William had realised one of his greatest ambitions, to provide a school, if not for his own children, at least for the grandchildren and others in the village. He had personally made the forms and desks.

"Make sure you learn to add and subtract your money properly," William advised the apprentices. "Don't fall into the trap that Stephens and Leycester did over the 'Disputed Plains'. They didn't stop to calculate what their argument would cost when they began their litigation against each other. In the end they have both had to sell. And all over a plain that they could have divided in the first place."

NEXT >>

Accommodation for employees at the saw-mill. It had previously been built for apprentices at the shipyard and was called the "Boys' hut"

Accommodation for employees at the saw-mill. It had previously been built for apprentices at the shipyard and was called the "Boys' hut" Barque "Schoolboy"

Barque "Schoolboy" Coraki Cottage from left Magdalen, Frances holding Louisa, Arthur, Frances' sister Louisa, Magdalen junior, and Lizzie.

Coraki Cottage from left Magdalen, Frances holding Louisa, Arthur, Frances' sister Louisa, Magdalen junior, and Lizzie.