Chapter 17 PENNANT HILLS 1951

Penny, in her final year at the "Con" and I both liked musicals but her formal knowledge of music was great and mine was limited. Compared with her broad cultural experience I felt quite ignorant. Occasionally we would go to a five o'clock session of a film in the city. When we could afford it we got cheap seats (the "gods", the highest gallery) to stage shows. Also we saw the film "The Red Shoes", inspired by a Hans Andersen story, starring a red-haired Scottish Ballet dancer, Moira Shearer, portraying a girl tragically torn between love and her career. Musicals gave me an over-romantic notion of life, except perhaps for "The Red Shoes" in which other emotions prevailed over love. The ultimate would be to be serenaded by a tenor, with fairy tale emotion.

"If the hero sang of his intentions they must be sincere."

In my dreams my ideal man adored me and was willing to make any sacrifices on my behalf. He felt humble and wanted to die for love of me. He fulfilled my hunger for love and asked nothing in return but the privilege of worship!! Everything invariably ended happily.

Penny introduced me to the ABC Youth Concerts, held in the Sydney Town Hall beginning early and finishing by eight o'clock. Returning one evening after a concert, we missed the bus we had expected to catch from Hurstville. The next was over an hour.

"Let's catch the Peakhurst bus and walk from there," suggested Penny. "We'll get there about the same time."

From Peakhurst, the driver who knew that we normally went much further, took us another half mile or so and from there we set out to walk. At Penny's turnoff we parted and I continued along the main road. As I walked along the uneven surface in the dark in my best shoes, my feet began to hurt. These were not my walking shoes! Approaching the track where Penny usually got off the bus to take a short-cut home, I noticed a tall masculine figure standing reading a book with a torch under a lamp post. I crossed to the other side of the road and hurried on. Just as I drew level with him, he looked up from his book, moved towards me and called out. I didn't wait to find out what he wanted. I slipped out of my shoes, stooped and grabbed them in a second and raced off in my stockings. He stopped and when I looked back he was gone.

The next morning on the bus Penny asked me "Did you get home all right? My brother asked me to tell you he was sorry he frightened you last night. He was waiting for me at the stop I usually get off at and wondered where I had got to. He had forgotten your name."

"It never occurred to me it might be someone I knew. I should have looked properly."

"Next time we won't miss the bus."

"I'm expecting to move soon. You know, where I'm staying my mother is supposed to be there to mind their little boy instead of paying rent. He goes to school now but they still want someone for holidays and after school and my mother is hardly ever home. She gets home for a few weeks then goes back to hospital. She will go into a rest home in Hurstville when she is discharged this time. I mind him a lot but his holidays are not exactly the same as mine. Helen and Alan have been very good to let me stay this long."

"Where will you go?"

"Maybe to my uncle's place at Pennant Hills. He's away in Rabaul except when he comes home on furlough. Only my auntie and two cousins are there now. I don't know them very well, but I have stayed there sometimes when I can't get back here. I went to our school ball years ago with my cousin Clyde and I've been there after other late functions."

"I met them at your debutantes ball."

"Of course. They have offered to have me."

"Who will pack?"

"I'll have to do that. The worst will be sorting my mother's things. I don't think she knows what is there any more. It's really hard to know what we might need again."

"What about your furniture?"

"We don't have much furniture any more. It will have to be stored."

Her parents offered to store some things including Mum's glory box.

I threw out our "Billabong" name from Bankstown which had begun to discolour, and a Marine Certificate with my paternal great-grandfather's name on it, books which I felt I had grown out of and a lot of unidentified items. They were of no particular value to me and I had no idea if they were important to my mother. I suspect many of them were.

I was sharing practically nothing of my life with my mother, or my interest in space and geology, only the most matter-of-fact things. Her needs such as toothpaste and nightdresses I provided. I told her little of my activities particularly bushwalking, as they may have been seen as dubious and worrying. My planned move to Pennant Hills would make it very much more difficult to visit my mother and collect her washing regularly. Another home for her would be necessary and the family had a conference about this.

I was leaving Lugarno with regret in spite of its distance from the train - Helen, Allan, little Phillip also my friend Penny.

My clothes and all my other belongings fitted into the Globite suitcase Mum had bought when we left Bankstown. My cousin Ken collected me in his car, a red two-seater MG roadster with a "dicky-seat" instead of a boot. When I had stayed overnight at Pennant Hills I had shared a room with my cousins Kathleen and Isobel. They had both gone to the Griffith district, leaving only Ken and Clyde at home. They were both in their twenties, I was eighteen. My seventh "home". The date was 11th August 1951.

The house was solid brick with a telephone in the hall and a pan toilet in the outside laundry. When the house had been planned in 1914 by my auntie, it had to have an indoor toilet, but when sewerage finally became available, the requirements had changed. Auntie Clytie also had a devise, activated by running water, to spin the washing, saving wringing by hand or using a hand-turned mangle. Washing was a weakly task, mostly done by my aunt while we were at work or college. I could make myself useful with the ironing.

"Would you like to come yachting on Sunday?" the boys invited. "We can always use another pair of hands."

"That sounds great. Where's the boat? Where do you go?"

"It's a yacht, a VJ and we keep it on Pittwater. We'll go up in Ken's roadster."

"What else do you do?"

"We do lots of things, church fellowship socials, parties, balls... Clyde is a good dancer, he'll take you if you like dancing."

"I love dancing. When's the next event?"

"On Friday I think. There's a girl across the road who generally comes to socials with us. Her name is Cecily Platt. She's about your age. And there's a Scottish Dance soon if you like that."

My social environment expanded enormously. It was a very agreeable arrangement. My cousins had lived there for many years, in a rather stable community, where many of the neighbours had been there just as long and the children had grown up together. I met new people and learnt new dances. I observed carefully how sophisticated people behaved in different situations. It was not too difficult to copy them. Cecily was small and blond and feminine. She was a stenographer in the city and we soon became "best friends" and travelled together to Redfern from where I walked to college. We knitted and chatted to occupy the three-quarter hour journey. Cecily was far more temperate than Beverlee had been and I did not feel at all intimidated by her. I became almost part of the family.

Cecily's two younger brothers were often doing their homework, her parents read and talked while we discussed our patterns and materials. Mrs Platt was a small vivacious, energetic woman. Mr Platt was tall and placid, considerate. Richard, then about fifteen had suffered from asthma all his life and was extremely small and thin. When school exams were due he invariable became worse, missed a lot of time and invariably did not pass. When he had an attack at night his father sat up with him. He was promoted on his class work, excelling in drawing.

She invited me to join the tennis group on Saturday afternoon where I met George and others if I was not bushwalking. I made a short white tennis frock, to wear with white sand shoes and socks, as was the fashion. Sometimes we walked to the pictures in Thornleigh, the next suburb where there was a theatre.

Mrs Platt asked me "How is your cousin Ted and his family?"

"Oh they're all well. They generally come to visit on Sunday. There's going to be another baby. Ted's hoping for promotion to deputy headmaster soon."

"How is your mother? Any better?"

"No she doesn't get any better. They can't do anything for her in hospital. The only thing is a nursing home but all the patients are twenty or thirty years older. She's forty-nine."

"That must be depressing for her. And no hope of getting better."

"She always hopes but she never improves. I'm going to knit her a bed-jacket, she spends all her time in bed now."

"What does she do all day?"

"She reads and embroiders and talks to visitors. That's about it."

"How do you like Richard's drawing?" asked Mrs Platt, showing me some sketches he had done for school.

"That is very good. Do you copy or draw from memory?"

"Both. These are enlarged from small pictures. I wish I could go to tech or somewhere I could learn art. It's what I really like."

"What sort of art?"

"Commercial art. I'm not likely to be able to get an ordinary job."

"Don't give up dear," his mother said. "You are still growing, and you don't get quite so many attacks these days."

"I'm having trouble with my maths homework," complained the younger brother. "Can you help me Dad?"

Mr Platt tried but it was a long time since his school days and the problem was new to him. I looked at the problem to see if I could help. I could and did. After that my help was often sought and I felt so capable.

I was not required to pay board, but had to meet all other expenses such as fares and clothes and to provide whatever my mother needed, such as toilet articles and clothes which I made as needed. In the meantime she went into a nursing home at Artarmon and Auntie Dorrie once again took over her washing. Mum's brothers and sisters contributed regularly according to their ability and Bill who was working also helped. The fees were £7 a week.

I attended church a few times in Pennant Hills and went to the "Ace of Clubs" for social activities. I saw no reason to mention this to Mum. The minister of the Congregational Church gave interesting informative talks about astronomy and did not dwell on the usual traditional, repetitive mindsets about "good" and "evil". He modified his services in the light of recent science and there was more emphasis on our deeds in the world. Still nothing gave me a logical reason for their dogmas, I had learnt to question things and not accept a statement such as "Fear God and have faith" and "There must be a meaning to life. It's common-sense." I thought that man's desire for a purpose did not necessarily mean that there actually was a grand purpose. Some people thought the meaning of life was to leave something behind such as children. What of those who did not marry or have children? Was there no meaning for them? For others a meaning was to be continually "progressing", acquiring more worldly goods in order to be happy. I began to develop a philosophy about contentment, independence, conservation, individual willpower and community and personal responsibility. But I never saw my future without children which depended on finding a husband.

Abandoning the idea of the earth and man as being predominant, led to the acceptance of the enormity of the universe and the idea that the earth and man are of no particular importance.

We had believed that we Fort Street students were superior to those from most other schools and many of us had gained better passes in the Leaving Certificate. But at college it didn't matter any more. Academic achievements were not a measure of other abilities many of which were now more important. I did well in physical training, and satisfactory in my craft work and practice teaching. Biology was not so good. We covered the whole field from protozoa to primates, very superficially in one hour a week, but I did absorb some concept of classification and nomenclature. We usually helped each other especially preparing for exams and doing projects and found that co-operation led to better outcomes than competitiveness.

I was challenged by the requirement to learn EVERY WORD in the four prescribed history books for Primary School, including captions under paintings (Where is a painting of Columbus to be found? Who wrote an account of Magellan's voyages?) for which I got 100%. I also had to learn simple weaving, marbling and other craft, collect poetry and songs for Primary Schools, collect and name Australian wildflowers, which made me realise this was a gap in my knowledge. There was so much to learn.

I was overcoming my difficulties making permanent friends and trying new things. Now I hardly ever lacked someone to go out with. And I never felt vulnerable to undesired advances. Nobody tried to take advantage. Anyone who may have felt inclined probably knew I would assert myself.

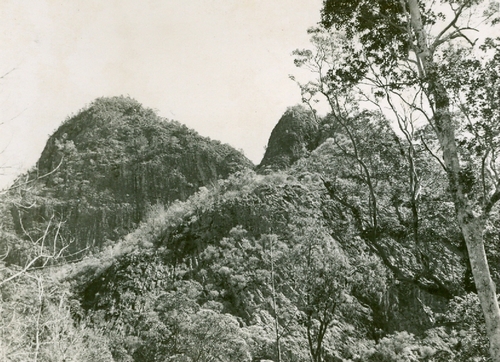

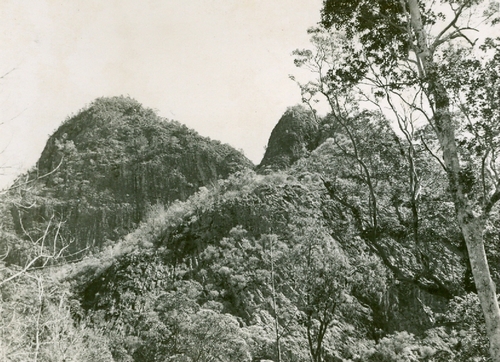

Egg Rock, Binna Burra, Lamington National Park, Qld Aug 1952 #

During the year the Kameruka Bushwalking Club had gone on a lot of trips and in August we hitchhiked to Lamington Plateau in southern Queensland. We passed through Surfers' Paradise which at the time was a paradise, soon to be "discovered". Thousands of boarding houses sprang up, each trying to outdo its neighbours with bright, sometimes garish colour schemes to attract attention, from Hawaiian to black and orange checkerboard. We were headed for a rainforest, growing in an area formed by an ancient volcano, which has been worn down to a plateau. There had been a major movement to create a National Park here in 1915 and I was beginning to get an inkling why it was necessary to stop endless development. By 1951 the area was interlaced with tracks, well-graded and well-signed, providing twenty mile round trips and half-mile rambles amid giant trees with buttressed roots, ferns and tangled vines, small rivers, waterfalls and cliffs that drop 2000 feet from Queensland to NSW. There was a smell of damp earth, tropical vegetation and undisturbed fallen leaves and the sound of many birds. We stayed at Binna Burra in our little tents and did walks every day.

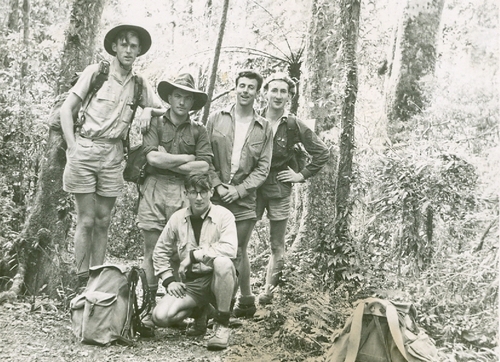

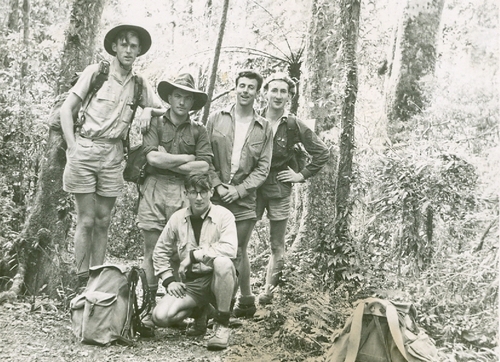

John Balderson, Dave Potter, Phil Plummer, Norm Allen and Brian Petrie (kneeling)

Lamington National Park, Qld Aug 1952 #

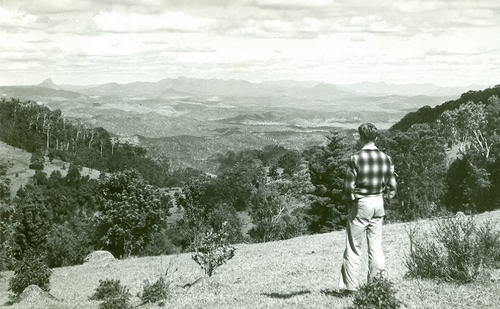

We also walked across to O'Reillys' Guest House where we camped and cooked our stewed veges and rice on an open fire. This was the place on which the film "Sons of Matthew" was based and where it was filmed. There we had a camp fire which some of the younger family members joined and we all danced in our walking boots to keep warm. One evening we saw Bernhard O'Reilly's "magic lantern" slides of the 1937 crash site of a Stinson, a small commuter aeroplane, in the rugged terrain.

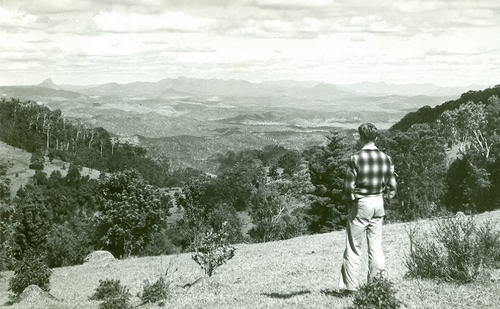

Postcard. O'Reilly's western view towards Mt. Lindesay and Mt. Barney

Lamington National Park, Qld Sept 1952 #

I was now exposed to many varied points of view and philosophies and as I had long ago rejected the dogma I had learnt as a child that there was only one "Truth", I was receptive to many areas of interest from geology, anthropology, archaeology, astronomy - any set of beliefs should change with greater insight. But I accepted the value of truthfulness, trustworthiness, integrity and co-operation as unchanging in my life. Most cultures valued these qualities for a cohesive society.

I had saved enough to buy myself a pack, from my allowance and extra earnings and this was a great achievement. I went up in the rattley "cage" to an Aladdin's Cave (Paddy Pallin's) to choose one of the lightweight, economical packs from his range and while I was there was amazed at the other goods - maps, books on trips, metal mugs, plates, cutlery, tents of various sorts, ski equipment..... The owner was a walker who had come to Australia and found a need for quality, lightweight, basic equipment, which he set about making and supplying. Bushwalkers agreed.

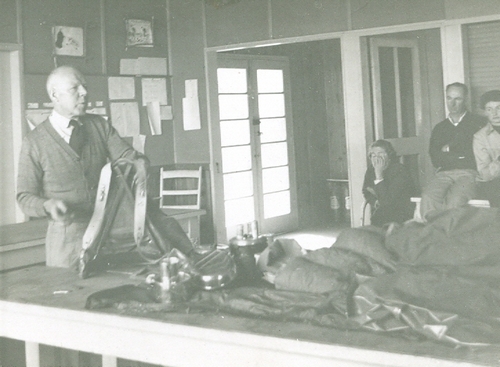

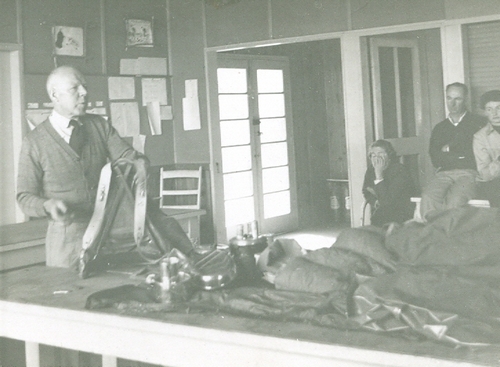

Paddy Pallin demonstrating new equipment, Sydney Teachers' College Bushwalking Camp, Lynch's Creek, Sept 1952 #

Being involved in activities was more important than looking good or passively looking on. Bushwalking was not very glamorous, particularly in wet weather. Pulling your weight, not complaining, sharing experiences won more friends, and good friends were more important than material objects. Seeing our country firsthand and trying to understand it were very rewarding.

To raise funds to buy more equipment, more packs and another sleeping bag, the club raffled an overnight bag. Cecily bought a ticket from me and won, so she came to the next club meeting to collect it and there she met people I had told her about including John Balderson. After that she sometimes joined our social activities.

Also to raise funds I helped to organise theatre parties, making a block booking in the cheapest seats ("gods") to get a discount. "Annie Get Your Gun", (Irving Berlin), was at the very grand Theatre Royal in King St. "Annie" was very spirited, had a mind of her own and eventually won her man, Frank, played by Hayes Gordon who stayed on in Australia to help found a theatre industry.

Towards the end of the year, the Ace of Clubs at Pennant Hills had a social dance and carol singing both of which I enjoyed. To me the carols were music rather than religion, some were very beautiful, especially appealing was "Oh Little Town of Bethlehem" and it was fun to knock on the doors of people we knew, who always found some sort of treat we could share.

Although Dad talked about taking us to the Barrier Reef, I made my own plans with my friends. We were going bushwalking in the Reserve in Tasmania.

Mrs Platt asked me "What about your plans for Christmas? Still going to Tasmania? Cecily has told me a bit about it after she went to your bushwalking meeting."

"I'm carefully working out the amounts of food I will need for ten days, with a bit extra for emergencies. I'm making cloth bags and collecting lightweight tins in which tablets come to the chemists. I've decided to lighten my load by cutting down on the amount of sugar I take in tea and I'm finding that I like it better less sweet. That's reduced the weight of my pack for a long trip by about a pound."

"By the way how are you getting to Tasmania?"

"Two other girls and I are meeting at Liverpool to hitchhike to Melbourne, then go across Bass Straight by the 'Taroona' on New Year's Eve. That was really funny about that raffle. Cecily didn't very much want to buy a ticket at all, she only did it as a favour, and then winning it! I think she enjoyed the slides she saw when she came to collect the prize."

"She might even go on a few easy walks after Christmas."

"We'll see about that," laughed Cecily, who enjoyed the outdoors but was not really the bushwalking type. She was an avid reader and often found travel books at the library which she passed on to me - Ernestine Hill and Gerald Durrell and I persuaded her to read "Green Mountains" by Bernhard O'Reilly about Lamington.

NEXT >>

Egg Rock, Binna Burra, Lamington National Park, Qld Aug 1952 #

Egg Rock, Binna Burra, Lamington National Park, Qld Aug 1952 #  John Balderson, Dave Potter, Phil Plummer, Norm Allen and Brian Petrie (kneeling)

John Balderson, Dave Potter, Phil Plummer, Norm Allen and Brian Petrie (kneeling) Postcard. O'Reilly's western view towards Mt. Lindesay and Mt. Barney

Postcard. O'Reilly's western view towards Mt. Lindesay and Mt. Barney Paddy Pallin demonstrating new equipment, Sydney Teachers' College Bushwalking Camp, Lynch's Creek, Sept 1952 #

Paddy Pallin demonstrating new equipment, Sydney Teachers' College Bushwalking Camp, Lynch's Creek, Sept 1952 #