Chapter 2 MIDGE

Eighteen months later Mum was enduring another difficult pregnancy. I wandered outside, climbed up the ladder from which Dad was working on the roof and started up his trouser leg. He sat me on the roof and moved me along as he worked. A neighbour saw this and it was quickly spread via friends of Dad's to the Kinny family at Kogarah. He was severely reprimanded but showed no contrition when he proudly recounted the incident to others.

He boasted "Midge", (Midget, my nickname), "is already a great adventurer." Being a curious child, I investigated everything and showed a lot of persistence and initiative and was destined to have an eventful life and to face many challenges. That suited me. He tolerated my inquisitiveness in small doses.

Nearly two years after my birth the next baby was due. Mum was again under a great strain. Not really sure about this new "brother or sister" prediction, I went out and picked some wild flowers growing in the yard. "Here Mummy" I said. "These will make you better."

Soon afterwards, as a little curlyhead toddler still wearing a terry towelling feeder after breakfast I was trying to "help" set the fire under the copper in the washhouse. My feeder caught on fire while Mum's attention was elsewhere but Dad was quick to remove it and quick to reprimand Mum for letting it happen.

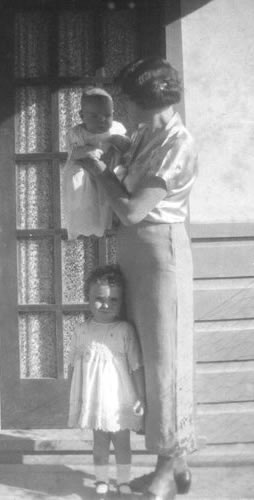

My little brother Billy, was born in Bankstown hospital, the day after my mother's 33rd birthday. Morven Private Hospital, the first in the area, was built in 1935; he must have been one of the first babies born there in January. William was a Kinny family name to which Mum added Andrew after her brother who had died in WWI. Fortunately for Mum, I was keen to help, quick to learn and my brother was particularly easy to manage. Mum still had ill health, but put on a brave front and so it was not realised how frail her heart was.

Dad had modified the sidecar to accommodate us. He brought his young sister Mollie and his young brothers Ernie and Bruce to stay overnight at Bankstown. Mollie was timid but Mum reassured her and she was soon comfortable.

When Billy and I were little we were taken to meetings of Jehovah's Witnesses and put down on the floor with a blanket and pillow and had to be quiet. The adults and bigger children read, listened to speakers, prayed, sang and shared their experiences around us and after the meeting talked and socialised.

When Billy was about six months old Mum was hospitalised with suspected food poisoning. Dad took us to our grandmothers to look after for a few days. I went to Grandma Kinny at Kogarah for whom I was the first grandchild. Grandma had working and teenage children who were captivated with me. My young aunt and two young uncles pronounced me to be very good and happy and were glad to entertain me. Granny Smythe at Ramsgate had the care of one of her youngest grandchildren, who had to be hastily weaned. Babies' bottles were shaped something like a banana with a teat on each end which assisted cleaning. Both grandmothers had raised large families with competence and nobody ever suggested they could not cope in time of need.

Dad said Mum should have known better than to eat meat that was "off".

Grandma Kinny said "We all do it. It's hard to keep meat fresh. I usually try to disguise it, but you can't afford to throw it out. It costs too much. I've got a meat safe which is OK for a few days."

Jehovah's Witnesses did not celebrate Christmas or birthdays but I have a memory (or false memory from being told about it later?) of Mum making a cake for my brother and me whose birthdays were a few weeks apart, and putting it on the dressing table in the bedroom. Apparently Mum reasoned we were not celebrating birthdays as the date did not coincide exactly and it was just a cake. At nearly three I was determined to investigate the pink and blue icing and three candles by dragging my highchair along the hall to the bedroom to see it, but having attracted attention to my project, did not succeed in doing much more. Cakes were a rarity in the house, although we had ample eggs. Grandma Kinny was good at cake-making, so Dad told us, no doubt we children were not critical of Mum's effort and would not have made comparisons.

Mostly we ate in the kitchen with Grace before meals. Breakfast was rolled oats with milk and brown sugar. Lunch was brown bread with vegemite, cheese and jam. Dinner was grilled chops and tomatoes, boiled potatoes and pumpkin, peas, beans or spinach. I didn't like stews much and was glad we didn't have them often. Another standby was macaroni cheese. Occasionally we had roast lamb, which provided cold meat for lunch and anything left was hand minced with a mincer clamped to the kitchen table to make shepherd's pie. Fat from the roast was saved in a special tin.

Mum did the gardening (with my help), mostly vegetables, especially melons and was pretty successful. A great treat in February were our own juicy peaches, fresh from the tree or bottled for later. Rarely were there sweets, sometimes date pudding with custard or stewed fruit when there was plenty, with jelly, custard (made of custard powder or eggs whisked with an egg beater) or junket (made with junket tablets to set the milk).

After every meal Mum boiled water in a kettle and we washed up in tin dish on the scrubbed wooden table which stood in the centre of the kitchen, using scraps of bar soap in a wire "soap-saver". The dishes were dried with a tea towel, immediately put away in the dresser and the water thrown on the garden from the veranda.

The washhouse was an unlined room at the back with a skillion roof. Most people washed in the backyard, often lighting a fire under a tub in the open. On wash day Mum lit the fuel copper in the washhouse with sticks and twigs gathered from the block and kindling and small off cuts of wood supplied by Dad to boil the water. The bottom sheet was taken off the beds, the top sheet put to replace it. First the sheets and pillowcases (always white) were boiled with grated bar soap, then lifted out into the cement tubs with a copper stick (a strong wooden stick) to be rinsed. Colourfast things were washed next, then coloureds, followed by extra dirty clothes and finally hand-washing in the warm water using a corrugated scrubbing board in the tub if necessary. At first everything had to be wrung by hand until Mum got a wringer which was hand-turned and squeezed out a lot more water. Linen tablecloths were given a final rinse in clean water with blue-bag to keep them white. Special things such as tablecloths, fine blouses and d'oileys were lightly starched so that they were crisp. Everything was put into the cane basket and carried to the line.

In the back yard was the clothes line, two posts with "seesaw" arms, with two wires for the clothes, supported in the middle by a clothes prop, a long forked stick, so that the clean clothes did not drag in the dirt as they were put on the line with "dolly" pegs. I could pass the pegs from a hessian peg bag. The clothes were soon flapping in the breeze.

There was also a "chook yard" with a chook shed at one end. All kitchen and garden scraps went to the chooks which was a very normal way of disposal as there was no garbage collection. Scraps were supplemented with pollard and shell grit and the water checked.

The outside lavatory had squares of newspaper stuck on a nail for toilet paper and a pan toilet which was emptied weekly by sanitary men ("night soil men"). There were two peach trees in the yard, a beautiful slip-stone near the house and a cling stone near the chook yard.

When the clothes were dry they were folded into the cane basket and carried inside. By this time it was mid afternoon and Mum was exhausted.

Ironing was done next day on the kitchen table on an old blanket and sheet. Mum had a modern electric iron (no thermostat). Clothes to be ironed were sprinkled with water and carefully rolled.

To visit Granny Smythe Mum had to take us to Bankstown station, catch the train to Sydenham and change trains which involved going up and down the steps, travel to Kogarah and face more steps. Then a trolley bus took us to Ramsgate and a short walk brought us to our grandmother's. This was a big day and left Mum worn out. As Billy got too heavy to carry far, Mum took him in the pusher. Going up and down the railway steps was tedious and I wanted to help but mostly someone of a suitable size was available. Uncle Perce and Auntie Dorrie had paid a local girl to work for them, and now paid for her to come regularly to do the washing for Granny Smythe and generally help as a "maid". She sometimes took me and Billy for a walk and sometimes even came to Bankstown to help.

Both of Mum's sisters were living out west. They had each married a returned serviceman who had balloted for Soldier Settler blocks near West Wyalong after WWI. By the time I was three and Billy a year old, Granny Smythe was boarding the two oldest of Auntie Vi's seven children so that they could attend High School. The oldest of Auntie Ida's four children was also nearing High School age.

Granny Smythe's house, built in 1914, was very small and the block of land was narrow with an outdoor pan lavatory, clothes line and a tiny lawn. One hot day when we were visiting, Granny Smythe put on the hose on the back lawn to give me a "shower". She was a great tower of strength, always available and supportive, could be very outspoken, but never interfered in domestic situations.

When I was three Dad sold his motor bike for £10 and bought a Hupmobile car for £10 from his brother Norman. It had a magneto which Uncle Norman could not manage. It had to be cranked which Dad said was OK if the battery was good and big enough. The car had a glass windscreen and the side windows were made of perspex, a clear plastic flexible sheet. When these became old and discoloured with age, Dad who had previously made a tent using his mother's heavy-duty sewing machine, made another set of windows. He spent a lot of time working on the car. We could watch so long as we didn't ask questions, or chatter and distract him. Soon afterwards Dad went alone on a trip to Tasmania.

In August something happened which I could not understand. I was protected from the tragedy as well as possible. To everyone's horror Granny Smythe died suddenly of "cerebral haemorrhage". Mum said it was inconceivable that she was no longer there. Most of the family believed their mother had now gone to heaven and was reunited with her son and husband and where they would all be reunited eventually. Jehovah's Witnesses did not believe this. They did not believe in heaven and hell. The dead simply went back to dust like any other creature. The righteous would be resurrected after Armageddon to live again on a perfect earth where there would be no more death.

My mother was distraught. Where could she turn? Dad was still in Tasmania and would not have been empathetic. Her beloved youngest brother, a favourite, happy-go-lucky member of the family, died soon after from double pneumonia and pleurisy, leaving his wife with two small boys.

Her sister Vi and husband Bill had to sell up in the country and move to Sydney to a rented house to continue the education of their two children who had been boarding at KY. Her sister Ida and husband Charlie also came to the city as their oldest daughter was ready for high school. They rented KY, the rent administered by her older brothers and distributed once a year to each family member.

So my mother had her two sisters within visiting distance for the first time in about 16 years. Her three older brothers also had children of high school age and altogether I now had lots of aunts and uncles and sixteen Smythe cousins in Sydney.

Among my early memories is a visit to the Botanic Gardens where there were child-size flush toilets which were convenient for us to use independently (more frequently than we needed to). These perhaps had greater importance than the wonderful trees and flowers and the large number of cousins to play with. We were allowed a lot of freedom and were quite used to making up our own games, some a bit adventurous following older cousins, but always knowing what was not acceptable. Auntie Vi also organised memorable family picnics at Taronga Zoo, which involved a ferry trip from Circular Quay.

My father did not join these outings and mostly went on trips alone, once bringing home a piece of sugarcane after visiting the North Coast. The only Kinny function I believe we attended was Dad's older sister's wedding when I was about two, Billy a baby in a basket. Dad took us to Melbourne once on a camping trip about 1937 to a Jehovah's Witness convention. He prepared the camping gear and car and sat in it warming it up impatiently, even tooting, while Mum organised everything else - food, spare clothes and children (with my insistent help). At street intersection there was often a traffic dome, a "fried egg" (because of its colours) or "silent cop" to mark the centre of each road which vehicles had to keep on their right if they were turning. We soon left these behind as we headed along the highway.

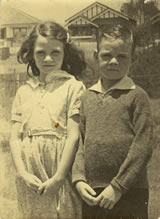

Billy, Dorothy and cousin Betty

Dad always carried a canvas bag of water hanging from the front of the car. We often drank the cool water straight from the bag, or sometimes it was used if the radiator ran dry. I vividly remember bull ants near our camp site and developed a healthy wariness of them, although I regarded all living things as part of my world, snakes, spiders, ticks and leeches, to be avoided but not condemned as they were all God's creatures. The sound of the car engine taking us somewhere, it didn't matter where, was stimulating and hinted at anticipated adventure and discovery until I got tired, then it was soothing and brought sleep. I remember nothing else of the trip.

Dad still mostly went to work with a friend in a sulky, which saved petrol. If he was going out in his car, he sometimes allowed Billy to ride on the running board as far as the corner. One day he forgot to stop and Billy was so quiet he just sat patiently and did not make his presence known.

"Billy Billy" I screamed running after them. At intersections "give way to the right" was the rule. At the next corner Dad had to give way to the baker's van and the baker called out "Got a stowaway?" and Billy had a long way to walk home in his pyjamas. Mum came hurrying up to the corner. I got there first and was relieved to see Billy coming tearfully but safely towards me. Dad had probably roused on him for not speaking up.

Dad was proud of his various skills and also his muscular strength, perhaps a compensation for his lack of height. Although he was usually busy with things which were to him more important than talking to children, he said he would take us to Scotland, home of one of his ancestors, telling us it was a very, very long way. He teased Mum about her Irish background. Bankstown had previously been called Irishtown because of the large number of Irish migrants who had settled there. Mum communicated with us much more, answered our questions, listened to us and told us stories about her childhood and family who had originated in Ireland. She sang us some Irish songs. There was a gramophone record in our small collection of "The Road to the Isles" about the Far Cuillins on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. It spoke to me of faraway wonders. Why couldn't we go to Ireland and Scotland?

One day my mother was in the kitchen trying to open a jar of jam - first with her hands, then hitting the edge of the lid with the back of a knife, then boiling up the kettle on the gas stove and holding the jar upside down in a basin so that only the lid was in the hot water. Still the lid was stuck so she opened the kitchen door, held the lid in the door-frame, closed the door as far as possible and turned the jar with all her strength. My father came in at the moment of success. He was scathing.

"What are you trying to do? Destroy the timber frame? Damage my house? Look at the dent!"

"I couldn't get it open," Mum admitted. "The lid was stuck."

"You don't have to destroy the house to open a jar of jam."

I knew she would never have touched one of his tools under any circumstances. I had seen her use a knife as a screwdriver. He was so strong he could have done it easily and I learnt later that he had no concept of anyone else's difficulties.

"You should eat up your spinach and get strong and I'll take you climbing."

Mum said "I'm afraid you'll leave me behind."

"You're out of condition. You need more exercise."

Dad was considered a competent artist especially technical drawing. Once I asked him to draw a cat but he declined. He did little to relate directly with me. Mum obliged with a primitive sketch of the poor cat which pleased me, but Dad ridiculed it. Mum was happy to include both me and my brother in "helping" her with the chores and explaining why things were done a certain way. Dad, did not give reasons for his demands, but expected immediate action.

Our milk came from a neighbour Mr Britton, who ran his cow on our block. The cow ate our grass, the owner gave us milk which we had to collect daily in a billy can. I was entrusted with this job as soon as I was big enough to carry it carefully. The owner showed me trays in his "dairy" in which he set excess milk in a warm place to collect the cream when it rose to the top in a crinkled skin. Collecting the milk one day I saw the owner kill a chook with an axe and chopping block and I was amazed to see the bird still running around without a head.

Once the cow got into our clover and got bloated. It had to be shot. If a cow ate too much easily fermented food, its first stomach (the rumen) became bloated with gas. It was not long before another cow appeared. Mr and Mrs Britton fostered a number of children after their own had left school and plenty of milk was essential.

The only other drink for us children was water, for adults in our house was tea. Most people bought milk at the grocer's shop, taking a container to hold it, served by dippers of various sizes, 1 pint or 1 quart. Or it was delivered by the milkman,with a horse-drawn cart, measured into jugs or other containers left by the door. Also delivered were delicious-smelling loaves of fresh bread. We mostly had a round cottage loaf of brown bread. And blocks of ice for ice-chests, the "bottle-oh" and the clothes prop man came less often. The bottle-oh collected bottles in his cart and earned a living by returning them to the factory or glass works. The clothes prop man cut saplings in the bush of the appropriate length to replace broken ones.

The sanitary man came weekly in a truck at night or very early, replacing full cans with empty ones which smelled of strong disinfectant. To some people the common name was "dunny" but this was not acceptable in our household. The pans were "tarred" at Milperra Sanitary Depot ready for redistribution.

The postman blew his whistle when he had mail for us. As there were practically no telephones, this was the main means of communication with friends and family. The baker, grocer, greengrocer, butcher came around the streets daily, mostly in horse-drawn carts with limited supplies.

Behind the kitchen door hung a razor strap for the purpose of enforcing obedience. But punishment was seldom used and there were not many restrictions in our lives so long as we stayed within our yard, were not cheeky and did not shout or fight, got permission for anything new and never touched tools or utensils from the house or Dad's garage.

We were used to entertaining ourselves with anything that came to hand and had a carefree childhood, mostly played barefoot and wore a minimum of clothing. We had few toys and needed few as there was a large backyard, a creek to play in, with frogs, tadpoles and paper boats, trees to climb, cubby houses we made ourselves, mud in wet weather, room to run, space and freedom. We dug a large hole in the yard and made roads and played imaginative games. We also climbed on to the roof of the chook shed and from there leapt into the air to "fly" for a moment. I dug a hole with the gardening fork "planted" Billy in it to be a tree, and then dug him up again, unfortunately misjudging where his feet were. He stood there, not moving, but objecting fiercely.

Our interest in our natural surroundings was fostered and everything was examined with curiosity. Mum helped us plant wheat or bean seeds in a jar between the glass and blotting paper, keep the blottting paper damp until the seeds sprouted, observing the leaves and the roots, but not eating the result. Why not?

When a kookaburra sat on a branch with his head on one side until he dived and dragged up a worm, I was fascinated. I thought kookaburras sounded happy but crows were melancholy. Had they lost their mothers? We were aware that the cicadas making such a din in summer, had struggled out of their empty shells, and after drying their wings had flown away. We believed everything around us was made by God for a purpose, to be used by us when needed. Our curiosity about everything was a natural, God-given instinct. We used gum tips in a vase when there were no flowers. One of the gum trees was ideal for climbing and for a rope swing. About this time Arbour Day was promoted, and Wattle Day waned. Hungry or not we ate the gum that oozed from old wattle trees. But the biggest attraction was the creek diverted into a drain next to our block with tea trees (Leptospermum) growing along the bank, beaut for cubby houses and cool places to dig and make roads.

Apart from the Bible there were few books in the house. Children's books were rare. With difficulty Mum had saved (or saved coupons?) to buy a large red book called "The Children's Treasure House", which contained many extracts from classical and contemporary writers. On rainy days Mum read us selected stories and poems from it. As we got older we progressed to those she considered to be good literature and avoided fairy tales, especially Grimm's stories which were too gruesome and even worse, they were based on enchantment and magic. There were few coloured illustrations, most were black and white drawings, many were grotesque representations, others were similar to those in the original books from which the stories came. Billy and I were allowed to colour these carefully, using crayons, pencils or chalk as available. A substitute rubber or eraser was a piece of bread formed into a ball. The book introduced us to traditional stories, poems and fables by many authors, which in later years included Shakespeare (retold by Charles and Mary Lamb) and Dickens.

The word "bored" never entered our vocabulary. Even on rainy days we found things to do, sometimes under the house where we made mud pies. For our creative activities indoors we made substitute paste of flour and water and cut out with Mum's scissors. If a rare coloured picture was available we used it to make a jigsaw puzzle. One of my favourite things was a kaleidescope, a tube with pieces of brightly coloured glass reflected in mirrors to form wonderful patterns. I learnt to sew a button (chosen from Mum's button tin) on a piece of material (chosen from Mum's scrap bag).

We were allowed to play the few records in our collection, carefully winding the gramophone and even more carefully bringing the head with its needle (which had to be replaced frequently) to the beginning of the grooved part of the record and lowering it with greatest care. From a very young age I tuned in to "Intermezzo from Cavalleria Rusticana" and was transported by the music.

Although there were no Christmas presents, we were taken to the city and saw the Christmas displays. Once we were in the city after dark and saw the coloured lights and neon signs, some of which went on and off and appeared to move. To us it was a magical Wonderland. A neighbour felt sorry for us having so few toys and gave us some. She gave me a little doll, a "wetums" doll which had a hole in the mouth for its bottle and another to wet its nappy. It was made of hard plastic, more durable than celluloid, (an early plastic which was light, easily broken and flammable) and I think Billy got building blocks. He wanted a doll too and Mum gave the matter careful consideration, concluded it was appropriate for him to have a boy doll with a biblical name. She found some material, the better parts of clothes that were beyond mending, made a doll shape, filled it with sawdust which was plentiful in Dad's shed, and made a suitable outfit.

"His name is Samuel," said Mum. Billy did not play with it much. Dad encouraged him to "be a boy". From a very young age Billy had a corner of Dad's bench in the workshop with a set of miniature tools hanging from it and was encouraged to learn how to use them properly. I was excluded from such exclusively boyish activities. Later Billy had a tricycle and sidecar given to him.

Billy had the habit of sucking his thumb in bed, in winter, using a tiny feather from the eiderdown in the crook of his index finger, to tickle his upper lip at the same time. Sometimes there was a hunt for the feather at bedtime or he used fluff pulled from the edge of the blanket.

NEXT >>

Billy, Dorothy and cousin Betty

Billy, Dorothy and cousin Betty