The Post War Years

As Vern was one of the first to enlist, he and his young wife sailed for Australia early in 1919 on the "Orsova". Mary cried herself to sleep every night, feeling that she would never see her father again. Vern did not know how to cope with this. Her fears were well founded as her father died soon afterwards, leaving Margaret Hyndman to manage the farm estates. Among other problems there was trouble with Sinn Fein. On one occasion she took an ancient blunderbuss and threatened them. They departed and left her alone. In time she would follow her daughter to Australia, and so did her son William.

Mary and Vern

Mary and Vern

When Vern and Mary arrived in Sydney they stayed for a while at KY with Ted, Annie and five young Smythes in the two-bedroomed cottage. Annie had had a fall and hurt her leg again and varicose veins broke out again. The doctor recommended three months off her feet. The girls were old enough to help, although they were all working.

Mary unpacked her trunks and put her things out to air. The girls were amazed at her trousseau, especially the forty pairs of shoes. As a gift for Annie, her mother-in-law, she had bought a Belleek tea set from the famous pottery in Northern Ireland which had survived a threatened closure and was gaining a world-wide reputation. The set was iridescent white, fluted shell-like and very delicate.

In Australia, Mary found herself in a completely new situation and was dismayed to find that Vern's folk had NO social standing. As her family had always had domestic help she had never learnt to cook. She decided she must learn, and that she would learn to do it well so she bought some recipe books and set about practising. They moved to James St, Lismore when Vern got a job in the electoral office there. He now found it boring so began to learn accountancy and insurance adjusting. He set out to improve his social status and felt at ease in any company including the well-to-do. To her new in-laws Mary was very formal. Vern jocularly referred to himself as the "little black-haired boy", Bert's nickname for him.

In March 1919 Viv became a temporary major. While on leave in Ireland he visited Mary's family at "Trentagh", Carlow, the birthplace of his grandmother (Maria Lawlor), also County Tyrone, the homeland of his grandfather (Andrew Currie) and Scotland where the MacPhees, Clytie's family, had come from in 1842. In July he sailed for home in charge of the draft on the "Chemnitz", bringing his collection of rifles, German helmets (six), pistols, bayonets, an antitank shell and grenades. Believing there would never be another such war, he kept souvenirs of the great event*.

At the end of hostilities Perce's battalion was in Belgium with the occupation forces. He bought a book of German to have a smattering of the language and was able to take leave to go to Cologne and along the Rhine by train to Strasbourg, seeing castles and cathedrals and galleries, which greatly impressed him. In April he was back in England for his investiture. He was among the recipients of medals to be invited to Buckingham Palace for presentation by the king. The king spoke to each person as if he knew why the medal was awarded, but Perce felt that the citation bore little resemblance to the way it really happened. He thought the king was happy to be performing the ceremony even after two hundred presentations. Perce received a silver cross with a purple and white ribbon pinned on his tunic, also a warm, manly handshake. Too late he realised he could have taken Dorrie to the ceremony.

Her family still did not approve of him as a son-in-law and would not give consent. Her father did not have an appreciation of Perce's intellectual capacity. Also Dorrie’s singing teacher said she should continue her training in music and not give up a musical career to marry at the age of nineteen. As soon as possible Perce went to visit Dorrie's family and believed her father was getting more affable, but would not allow his daughter to go to Australia as she was needed to help look after the two younger children, Wilf and Betty aged ten and seven. Perce offered to stay in England until July. Her parents would only agree if he promised to stay indefinitely. This he couldn't do as he had promised his mother he would come home.

As a wedding present for friends he gave a copy of a sketch he had done of the ruins of Corbie cathedral during the war. While waiting to go home he elected to do an art course from April to August 1919 at Kensington at the London School Of Art.

Dilemma

Percy and Dorothy

Percy and DorothyThe young couple had their own ideas about their future so they made arrangements to marry in Glasgow. Mr Jewell said "If Dorothy goes to Scotland she won't come back here". When Dorothy thought her parents were about to relent, they cancelled. Finally she had to go to Glasgow for two weeks to establish residence, and Perce joined her and they were married on 7th June. They had a honeymoon on the banks of Loch Lomond. Perce was absent without leave from the art course but his name was answered by someone else at rollcall and he was not missed. Back in London they found that Mrs Morgan was angry at what they had done, so they stayed elsewhere. The long-term friendship went sour.

Perce and Dorrie rowed on the Serpentine, walked five miles from Kensington to Kew Gardens where the tropical house reminded him of Mt Comboyne and Koppin Yarratt, looked at the decorations for the celebration of Peace, witnessed the Victory March and saw the King and his family on the balcony at Buckingham Palace. After four years of menacing explosions, shell bursts and flares, Perce found the fireworks display symbolic and spellbinding. He even let off some flares of his own.

"This marks the final closing down of the world war and the dawning of the life of peace".

After making preparations to sail, they had a brief visit to her parents and Perce promised that he would agree to Dorrie going home for a holiday after seven years. The young couple sailed on "Anchises" on 22nd August, going via Capetown and Durban.

Officers were allowed to bring their wives on the same ship, but they were disgusted to find they slept four officers to one cabin, their wives at the other end of the vessel. No doubt those involved came to some arrangement. Dorrie suffered from seasickness, and as well began to suffer from morning sickness.

Perce brought back with him many sketches including one of Corbie cathedral and later did an enlargement of this. His nerves and health were affected by his war experiences, causing nightmares of being drowned in mud. Dreams that Bert was still alive and walking down the street with him resulted in bitter, sickening disappointment when he woke.

They were unaware that in Sydney, Perce's father, Ted had met with an accident two months earlier. He had not been well and had been advised by the doctor to give up work but had not done so. In the habit of getting off the tram on the wrong side in King St Newtown, near where he worked at the time, he apparently did not notice an ambulance going past stationary vehicles. It struck him and knocked him unconscious. After the accident his pay, containing his week's takings was missing and his family suspected the ambulance officers.

Admitted to nearby Prince Alfred hospital, Camperdown, meningitis set in. The family took it in turns to sit with him. Ida was afraid he might die while she was at the bedside. One day when Viola was there he came to and said "Dear Vi" before lapsing into unconsciousness again. These were his last words. Five days after the accident he died, aged sixty, and was buried at Woronora cemetery. Vern came down from Lismore where he was working and he was the informant on the death certificate. Viv arrived home a week or so later. At the inquest the next week it was found Ted had died of accidental injuries after being "knocked down by a motor ambulance wagon". His estate was valued at under £5. By this time a small pension was available and Annie would be eligible. She was issued with a handwritten pension card which she took to the Post Office to collect her 10 shillings a week.

When the "Anchises" arrived at Adelaide in October, Perce and Dorrie were informed of his death. A letter written two months earlier had finally reached them. Perce wrote, "A cloud of sorrow that overshadows us seems to have taken away all the pleasure of the home-coming."

Arrival in Sydney.

Arrival in Sydney.

Back row L to R: Vi, ?, Dorrie, Percy, Annie, ?

Front L to R: Eric, GordonAt Sydney, Annie, Viola, Eric and Gordon met them with details of the shocking news. In the last two years Annie had lost her eldest son and her husband. Of Annie's siblings only she and Robert had married and both were now widowed.

While Viv was away, Clytie had continued to work for the Gaslight Company. When he got home with his arsenal of souvenirs, he got a job at West Wyalong with PMG. He and Clytie had another photo taken, he in his officer's uniform and sporting a  moustache, she in a smart long skirt and coat. He never talked about the war to his family except to describe the investiture by the king, his invitation to the opening of Australia House in London, and his visits to the family homelands.

moustache, she in a smart long skirt and coat. He never talked about the war to his family except to describe the investiture by the king, his invitation to the opening of Australia House in London, and his visits to the family homelands.

Like Mary, Dorrie found Australia very "different". She and Viola were similar in height and disposition, the former being a redhead, the latter fair-haired. Like Perce, Viola called her sister-in-law Dorrie and the name stuck. Viola was mostly called Vi. Her daughters-in-law began to call Annie "Mum Smythe". For a while Perce and Dorrie stayed at KY. The photo of Bert, surrounded by Perce's sketches as a decoration was framed for his mother*.

By 1920 repatriation was complete. At this time Clytie, Mary and Dorrie were all pregnant. Margaret Hyndman, now a widow, came out from Ireland to be with Mary when she heard that she was "expecting". A big woman with beautiful hands, a regal appearance, magnificent when dressed up to go out she was very formal. People did not "drop in".

At KY the following year Dorrie had a daughter who was named Betty after her young sister in England, but the baby was stillborn. After the confinement Perce took her to Stanwell Park for a few days to help her recuperate, before going to Bowral where they started farming. Because of his chronic bronchitis, contracted in France, Perce had been advised to work in the fresh air. He had a small war pension, because of his indifferent health. Every day he continued to do exercises and tried many remedies for his health; taking paraffin oil for bowel problems he had developed, religiously cutting the fat off his meat, but piling the butter on his bread!

For her twenty-first birthday, Perce gave Dorrie a piano and she was soon playing competently again. Although diminutive in size she had a mind of her own, knew what she wanted and had a lively nature. As a young wife, who had lost her first baby and was far from her family and her beloved homeland, Dorrie had some difficulties adjusting to life in a new country.

Grandsons

In August, a year after Ted's death, Clytie who had previously lost a daughter, gave birth to her second baby, at a private hospital at Epping, Sydney, this time a healthy son, named Herbert Edward Vivian. His names were partly after his Uncle Bert, his father and his grandfather. As a child he was known as Bert. At the time Viv was still employed by the PMG and working at West Wyalong and the family was staying at "The Haven" at Pennant Hills.

Not long afterwards, Mary gave birth to a son at Lismore. He was called William after her brother in Ireland. Mary had a very difficult labour and was in hospital for nine weeks. The baby was delicate and his mother did not see him for some time. Vern had finished his accountancy course, and had been asked by the college to stay on and lecture, possibly at night classes while he worked for a brewery. Some months later Mary’s mother went home to Ireland. There were major troubles at the time. As she had sold "Trentagh" she had to stay with relatives and friends. The patriarch had died and left a substantial legacy to Margaret, Mary and William. Other members of his family who became Catholic were disinherited. When her welcome began to wear thin she returned to Australia permanently. Her son William also came to Australia and bought a property near Kyogle, but did not keep enough money in reserve for ongoing expenses. He became a baker in Goondiwindi and married a local girl.

When Vern had been working at Narrandera before the war, he had become friendly with a family of Glasgows. The Glasgow girls had met the Smythe girls. After the war Louise (Louie) Glasgow brought her brother Bill to call on the Smythes at Ramsgate. When Dorrie first caught sight of him through the curtains at KY she joked to Vi, "Here is your tall, dark and handsome man."

Bill Glasgow

Bill Glasgow

Bill Glasgow was indeed tall, six feet two inches [1.88m] dark and handsome and had an erect military bearing. His grandfather had been born in County Tyrone and had grown up in the USA. In 1895 Bill was born in Narrandera, had attended Fort Street in Sydney until he was sixteen, passing in Latin but failing French, which prevented him taking up Law like his brother. He joined the Public Service, working for the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission and was sent to the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area until he enlisted and went to the Middle East and Palestine with the Light Horse.

When next he came to call on Vi he quipped, "Here is your tall dark and handsome man." Although small in size, Vi never allowed herself to be manipulated or imposed on. Bill admired her spirit and he also knew what he wanted. They planned to marry. She wanted both her sisters to be her bridesmaids, and to be dressed in trendy black and orange. They were dismayed at the colour scheme and resisted strongly.

After doing the Leaving Certificate, Ida went to Business College and became a shorthand typist. At a Presbyterian Church function she had met Charlie Johnston who pretended to be twins. His family had come from Selkirk, Scotland and had gone to New Zealand where his mother had died when he was little. His father had sent Charlie and his little sister Effie to Sydney to their aunt, who brought them up. During the war Charlie was in the navy, had been in Darwin when the war ended and had not waited around for official discharge. When he met Ida he became very keen on the shy and nervous, reluctant girl and would not take no for an answer.

The three older boys now had families of their own; Vi and Ida were being courted. Ida was the only one to finish High School, Rita looked well and was always cheerful which belied her weak heart, a legacy of Chorea. Disappointed that she could not join long walks, tennis games or energetic dances, Rita was watching her brothers and sisters marrying and having children. At social functions she soon became exhausted and sat out. After the death of their father, the two younger boys, Eric and Gordon, went to work wherever they could, Eric as a timber-getter at Nimmitabel after a short time at Fort Street, and later a machinist at Clyde Engineering. Gordon at the age of fourteen had a job (perhaps gardening?) for three ladies who gave him a book in appreciation of his willing and pleasant attitude.

After battling droughts and floods for two years at Bowral, Perce and Dorrie moved to Duntroon Military College where he got a job as groundsman, believing that outdoor work would help his chronic bronchitis. While there he studied for the Matriculation having been advised that a university degree would help him to be a successful writer. As an ex-serviceman he needed only four subjects instead of the usual six. With a little help from the College lecturers he taught himself English, Maths, French and Latin.

Bill and Vi Glasgow Charlie and Ida Johnston

Bill and Vi Glasgow Charlie and Ida Johnston

On 11th March 1922 Vi married Bill Glasgow, Ida and Rita were her bridesmaids having persuaded her to let them wear pastel colours. Vi and Bill had a long honeymoon in Kangaroo Valley.

Ida was also swept along into marriage. She finally accepted Charlie's proposal, but was very ill prepared for marriage, being unsure of herself, not a good organiser and knowing very little about the facts of life. Charlie's sister Effie was her bridesmaid. Bouquets for the girls’ weddings were a gift from people across the road who owned a nursery and flower shop.

Girls now wore their hair short which was very modern even outrageous when it first became fashionable as girls had always had long hair. Vi and Ida had short hair for their weddings.

Charlie had some money and was able to buy a car, the first in the family. Five of Annie's children were now married, leaving only the three youngest.

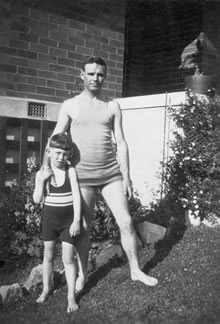

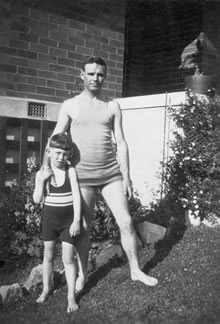

Mary, Billy and Viv

Mary, Billy and Viv

By this time Vern and Mary with their baby, Billy were living at Mosman, on the northern shores of Sydney Harbour. The baby had overcome his birth problems and was thriving. Soon afterwards they bought him a wooden rocking horse, the first such luxury in the family. Mary encouraged the family to give notice before visiting. This caused some coolness and even alienation from some of the siblings.

To get to the city or to Ramsgate, Vern and Mary caught a ferry across the harbour. Harbour ferries included Kirribilli, Kanimbla, Kiandra, Kosciusko and Kameruka. There had been proposals to build a bridge and John Bradfield had spent eight years preparing specifications on cantilever and arch bridges. The war had caused the postponement of plans. In 1922 an act was passed authorising the construction of a bridge to integrate road and rail on both sides of the harbour and cater for traffic into the future.

Visit from the Cousins

Eric, Ida, ?, Rita, Gordon

Eric, Ida, ?, Rita, Gordon Cousins Flora and Eileen kept in touch with the Smythes as they had a strong sense of family. Their father had built a grand house on his property at Myrrhee and owed a lot of money. When their brother Bobby disagreed with his father he had left home and worked at a sawmill near Narrandera. He soon went to Grong Grong, a small town nearby, the name meaning "a poor camping ground; very hot", or maybe the sound of a frog. Bobby bought a racehorse from which he bred, and lived in two or three big sheds. Like some of his Smythe cousins he liked drawing, his specialty being horses.

Later Flora and Eileen came to Ramsgate from Myrrhee for a visit. Her cousins were younger than Rita, but the girls enjoyed each other's company. Flora still enjoyed sports and was interested in competitive sport such as hockey and tennis. She continued competing in regional hockey and tennis until her forties.

Annie's two younger sisters, Allie and Fanny were still in dispute with the Council over the family property at North Winton. With every heavy rain the land flooded. They believed they had a sacred trust to continue the fight for justice. Since her sisters' lack of sympathy over the death of Bert, and the manipulation she felt had gone on over her father's will, Annie had not made contact. Her brothers had worked on the property and they should have got something.

In Tasmania their cousins Ernie and Alf Graham (whom the boys had met on the French battlefields) had married sisters Margaret and Ellen Manser in Launceston. Each couple took up a Soldier Settler block in the Devonport area and had one child but the marriages were not successful and ended in divorce. Their widowed mother Clara had struggled on with the farm in Graham's Lane, Derby while the boys were overseas at the war, but when they moved away she sold up and moved to Launceston, where she resumed her activities with St John's Church where she had been christened.

First Granddaughter 1923

Percy and Betty

Percy and BettyPerce and Dorrie were still at Duntroon when they had another baby, another girl, another Betty. She was born on 19th August at Queanbeyan and christened at Duntroon, the first granddaughter to survive.

As he had been discharged unfit, and granted a small pension, Perce obtained a scholarship to Sydney University but not to get his Diploma of Education.

When Betty was two, Dorrie took her for a trip back to her family in England, six years after she had left without their blessing. When the boat arrived they found there was a strike, and her parents had not been able to get to London to meet them. They got the last train to Yorkshire where her father had been sent by the co-operative chain of grocery stores which employed him.

During the absence of his wife and daughter, Perce stayed at KY. While studying he found it helpful to walk up and down the path at the back carrying a book in one hand and a pumpkin in the other. The two camphor laurel trees in the tiny front yard were now very large. They also planted a tree fern and a small hedge near the back of the house.

By now the trees and garden were well established. Annie had violets and maiden-hair fern growing along the side of the house of their neighbour Frank Jones to whom they chatted over the fence.

Rita attended a party at Hurstville, invited by members of the Shetland Island Society. She and her friend missed the train which connected with the last tram to Ramsgate, so one of the guests Harold Kinny offered to walk them home using the causeway over Kogarah Bay. Rita and Harold met again at the Resolute Hall Kogarah, where Scottish dances were held. Although she could not stand up to the more energetic reels Rita had learnt and enjoyed Scottish dancing. Her Irish forebears had come originally from Scotland in the days of the "Plantations". Harold's grandfather had come to Australia from Dumfries, Scotland, as a ship's captain finally settled on the Bellinger River and had two sons and eleven daughters. As a little boy Harold had attended Highland Games in a miniature kilt. The second oldest of eight children he now lived with his family at Kogarah, and worked as an electrician. When he met Annie, she asked him about the possibility of getting electric lighting put on at KY.

Eric and Rita

Eric and Rita

As part of his university course, Perce asked his brother Gordon and Harold's younger sister and brothers to complete intelligence tests. The younger boys were not worried but the young girl was very nervous and cried, but Perce comforted and calmed her. Gordon was shown to be very intelligent; in fact the brightest of anyone Perce tested. Gordon was also artistic and confident.

Out West

There were marches by returned servicemen who could not get work; one group demanding the jobs of people who had not enlisted. There was a fear that large numbers of soldiers home from the war to the cities might cause trouble, so the government developed a scheme to offer land to ex-servicemen. Vast areas still under leasehold were resumed. Other areas of land were bought; some people saying that large landholders had unloaded marginal land at high prices. It was cut into small lots in flat, dry "mallee" country, which was hot in summer and cold in winter. Viv was working with the PMG at West Wyalong NSW 300 miles from Sydney, when land at Erigolia, further west, became available. At the time Erigolia was bigger than nearby Rankins Springs; the two settlements being five miles [8km] apart.

Land was uncleared, with no water and millions of rabbits. The only reliable water was seven miles [11km] away at the "spring" in the hills after which Rankins Springs was named. Having decided which ones they would prefer, people balloted for blocks. The first name out of the barrel had the first choice. Several members of the family were interested, Viv Smythe, Bill Glasgow and Charlie Johnston. Viv had had some experience as a boy working for his grandfather on the farm at North Winton. Viv decided to ballot for a soldier settler's block at Naradhun (Erigolia). Their son Bert was two years old and another son Roy had been added to the family. Clytie agreed to sell "The Haven" to finance the venture, so it was put up for sale. Viv took up a lease of a homestead block one mile by two miles [1.6 x 3.2 km], south from the town common. It was called "Longfields".

At first, Viv was single-handedly running the PO, a HV McKay farm machinery agency and later the telephone exchange from the first "farmhouse" a tin hut he built in the corner of his block nearest the railway siding and the town. Compared with the comfortable brick home at Pennant Hills the accommodation on the property was crude. Earning a living had priority. There was land clearing, a major task, as the many-stemmed mallee trees with their difficult lignotuber had all to be dug up. As soon as the settlers could afford it, they bought a "stump-jump" plough, which had a counterweight to let it go up and over the stumps. In time Viv acquired one.

Then fencing, dam-building, bore-sinking, ploughing, cultivating and sowing had to be done. When the crop, mainly wheat was ready to be harvested, the rabbits ate it. Rabbit-proof fences were very expensive and if the gate was left open, the rabbits soon discovered the way in! Clytie had another son, Ken, by the time "The Haven" was sold and she was able to join Viv. Sometimes Viv employed a young man to help him and had to pay £1 a week plus keep, which was more than he spent to keep his family. His young brothers, Eric and Gordon also came to work, and his in-laws when their own work allowed. Viv was putting in fence posts.

Beau

Beau

Although she could not drive, Clytie bought a 1924 T model Ford and her brother-in-law, Gordon took delivery in Sydney and drove it to Erigolia. There was no need to get a licence, road rules were the same as for horses. While he was away wires had been put into the boundary fence and the car was driven straight into it! In spite of that mishap Gordon drove it as much as Viv.

Gordon had grown into a popular young man, known by his nickname, Beau, as many of the local girls were smitten with him. Some of the local youths were jealous and challenged him but soon found out he was very useful with his fists. He still admired Nellie Potter whom he visited whenever possible and planned to marry in due course.

On one occasion Clytie fired one of Viv's many rifles to scare off an intruder who was stealing their poultry. She was pregnant again and had another stillborn baby.

Viv's first small harvest was taken off with a horse-drawn McKay harvester. Someone else took over the PO and combined it with a store until it burnt down. Viv's second house was built near a small pine (Callitris glaucophylla) forest a mile south west of the original, intended to be temporary, and was gradually expanded as the family grew. It was always known as the "old tin hut". They needed a roaring fire in winter and the corrugated iron was like an oven in summer. Drinking water came from rainwater caught in a tank, but this was not enough for stock and crops. Water diviners or dowsers thought there would be underground or bore water.

For Viv and Clytie the "harvest" of 1925 included the arrival of daughters Kathleen in January and Isobel on Christmas Day. Isobel was usually referred to as "Bub" as she was the baby for a few years. While Clytie was waiting to go to hospital to have Isobel, she saw that draught horses had got into the wheat bags. This generated gas in the stomach and would kill them, as well as being a waste of wheat. She got out a pea rifle and aimed at the hips. The horse which was hit reared up and took off and the others followed in panic.

This was followed by a "bumper" year in 1926, when a tractor, a "Sunshine" McKay header harvester, and additional disc ploughs and "combine" cultivators and seed-drills were added to the farm plant. The harvest was heavy and early - so much so that Clytie's younger sister stood in as a tractor driver in the early stages.  They grew some vegetables and had their own meat. The vegetable garden was in the orchard, half a mile from the hut, where the soil was good and there was a reliable water supply. There were yabbies in the dam and beautiful mushrooms after rain. There were some chooks, and plenty of rabbits to eat. They had rolled oats and fried eggs for breakfast, dinner was rabbit and rice and pumpkin. Potatoes had to be bought. Clytie made limewater using pieces of limestone.

They grew some vegetables and had their own meat. The vegetable garden was in the orchard, half a mile from the hut, where the soil was good and there was a reliable water supply. There were yabbies in the dam and beautiful mushrooms after rain. There were some chooks, and plenty of rabbits to eat. They had rolled oats and fried eggs for breakfast, dinner was rabbit and rice and pumpkin. Potatoes had to be bought. Clytie made limewater using pieces of limestone.

Vi and Bill were living at Willoughby, Sydney when their son Robert (Bob) was born. Bill could not settle in an office job, so he applied for a soldiers settler block, and went west leaving Vi and the baby to stay at KY for the birth of the next one, a daughter called Nancy; like her Irish grandmother who had died before the family migrated.

Dorrie with Betty and Ida with Margaret

Dorrie with Betty and Ida with Margaret

Ida and Charlie Johnston were also out west on a soldier settler block in the same district. Their car was sold and they bought a horse and sulky. They could not afford a "stump-jump" plough and the mallee roots gave Charlie a lot of trouble. They had an eleven-pound [5kg] daughter, Margaret, born at Rockdale, Ida having come down to KY from Rankins Springs for her confinement. It was a very difficult birth and Ida needed a lot of stitches.

Vi and Bill Glasgow with two little children lived north of Erigolia in the most basic hut of split slabs. Bill said later it was the happiest time of their lives as they were young, full of hopes and dreams for the future.

When the young Smythes, Glasgows and Johnstons were approaching school age there was a petition for a school. The railway was extended further west and fodder could be brought in. At first, the settlers took the timber intended for the station buildings, which were subsequently made of cement blocks instead.

When Vi had a second daughter, Hazel, and Ida a son, David, they did not go back to the city, but went to the new Erigolia Bush Nursing Home, staffed by one nursing sister, in a small fibro "cottage" on wooden blocks built in an enclosure of one of the paddocks south-east of the PO. Previously there had only been a midwife to attend births. The nearest good medical service was in Griffith, forty-five miles [60km] away. The road was very sandy and full of gilgais, natural depressions, probably caused by swelling and shrinking of the soil in wet and dry seasons. The minister and Sunday school teachers only came out once a month on a motorbike. Services were held in the railway stations at Erigolia and Rankins Springs which were the only places with enough seating.

Nancy, Margaret, Bob, Hazel, David

Nancy, Margaret, Bob, Hazel, David

Hazel was taken home in a 1925 T model Ford and was christened at the Rankins Springs Railway Station by the minister who later went with John Flynn to work for the Inland Mission which set up the Flying Doctor Service.

In Sydney, excavations for the Harbour Bridge had began in January 1925. The Illawarra Railway line would be electrified, and trains would run from Central to St James station, as the first stage of the Underground.

Harold bought Rita a diamond engagement ring, which she proudly showed to her family. Harold who came from a very practical family had made her a beautiful inlaid jewel box, and was making a "glory box" or "hope chest" from a log of Siberian Oak for her trousseau. The timber had been left in Sydney Harbour to mature. He had plans to make a bedroom suite in the near future, and after the wedding to build their house with the help of his father and brothers. In the meantime he bought a motorbike and sidecar. It had belonged to a friend, who worked for the Water Board and had used the sidecar for his plumbing tools.

Harold decided to go to Erigolia and Rankins Springs with his motorbike and sidecar for a short working holiday between jobs. He saw Vi and Bill with three children and Ida and Charlie with two. Viv and Clytie with five children were not far away at Erigolia. Beau was also there working where he could, although he was unfit for heavy work because of his "rheumatic heart". He worked for Viv at harvest time, harnessing horses, driving the header, bagging wheat, loading the lorry and delivering it to the railway. One day Beau startled Clytie by holding nine-month-old Isobel by a handful of her clothing and making her gurgle.

Ida and Charlie had an iron hut without any doors. As Ida was terrified of snakes under the floorboards, Charlie had taken up the flooring and they were living on a dirt floor. Harold made them doors out of the old floorboards, also a bed for the babies. Ida put chaff bags over the frames, one at each end, but didn't have time to sew the two bags together in the middle. The children both slid to the centre and through the gap! When that was fixed the arrangement was satisfactory. It worried Ida that Margaret sucked her thumb and she scolded, punished and teased to no effect.

On Harold's return to Sydney, he commented that it seemed quite impractical to encourage city people onto farms in such remote marginal land. It was really sheep country cut up into small blocks for mixed farming for which it was not suitable, especially for untrained people. Harold scoffed that Charlie couldn't hang a door or even harness a horse.

Rita’s "Hope Chest"

Now that she had more time, Annie who was fond of crocheting did some very fine work. She made crocheted dresses for the babies, and for Dorrie, an afternoon tea cloth and matching serviettes with a butterfly motif in the corners. She also made a linen bedspread for Rita's glory box, with a wide crocheted trim all the way round, as well as smaller items such as milk jug covers with beads around them to keep the covers on the jugs and protect the milk from flies.

When grandchildren came to visit, she liked to sit them on her knee while she had a cup of tea, and spooned sweet black tea into them. On one occasion Bert was taken to KY and everyone went to Ramsgate Beach. He admired Gordon who did cartwheels on the sand and surfed in the bay as there was a swell caused by a southern breeze.

Annie still suffered with her bad leg and had her own recipes of aromatic lotions to rub on it, and cures for other ailments. She used acetic acid, methylated spirits, turps, blocks of camphor, sliced, for sore joints and muscles. A few drops of kerosene on sugar were used for sore throats. She wore fur to bed on her feet, to keep them warm and relieve the pain. She still had strong opinions and independent views leaning to the left, without suggesting people were not responsible for themselves. At times Annie and Rita were the only ones at KY. At other times Eric was also there. About this time Annie came out to Erigolia. She got splinters out of the children's feet with a soap and sugar poultice. She also helped boil down large amounts of sheep fat for soap, which lasted many years. As learnt from her Irish forebears, she recommended that they eat well-washed potato skins, which were good food.

Eric and Ada

Eric and Ada

Eric met Ada James, who had been born in England and come to Australia aged seventeen with her family four years earlier. The first impression she gave was that she was "sweet". She had short straight hair and a fringe in the current flapper style. She was inclined to be fussy and particular, with definite opinions. She worked in her father's shop and Eric came in often to buy things he didn't need, so that he had an excuse to talk to her. Eric married Ada in March 1927 at Bankstown and they lived in various places including an old bus. He was developing a strong sense of what he considered social justice. He was known for his jokes but they were never teasing or unkind, sometimes corny. "Do they have to pay you to be good?" "No" "Then you're good for nothing."

On the other hand Beau was more happy-go-lucky and got away with outrageous jokes. "How's your belly where the pig bit you?" was forgiven, even describing the food at Bill and Vi's when Bill and Gordon were "batching" as "eggstraordinary--boiled, scrambled, poached, fried for breakfast, dinner and tea."

Nellie was still keeping house for her father, brothers and young niece. The Potters did not want to lose their young housekeeper. She came out west for a visit and stayed with the Glasgows.

Nell and Beau

Nell and Beau

Gordon was ‘Uncle Beau’ to the children and was the favourite uncle, thought to be expert at all sport and could always be located by his cheerful whistle. He could do cartwheels and walk on his hands. He taught Bert to play marbles and always won all the marbles but always gave them all back again. He let the children "walk" on his feet, and tossed them over his shoulder. The children were entertained with his mimicry of Donald Duck or local people. He "caught" them all with his tricks.

In Sydney Beau and Nellie joined the social activites at Ramsgate pool, built a year or so earlier and Beau became very proficient on the high bars at the pool. It grew to include several pools, diving boards, towers, lighting until 10pm and even a small zoo.

Viv got cement to build a permanent house, but the cement got wet so they had to continue to live in the temporary house, adding rooms as needed. There was a cement floor in the kitchen, wood laid straight on the soil in the living room and main bedroom. It was large compared with the huts of the others.

From a young age Bert had to learn to help his parents, minding his little brothers and sisters and doing basic housework and farmyard jobs.

When the bore sinkers came through, they tracked the course of an underground stream and sank bores along it. On Viv's property the drillers brought up petrified pinecones before finally getting water at 400 feet [120m]. The bore was a quarter of a mile from where the hut had been built and water had to be carted in a furphy, a water cart made by John Furphy of Shepparton, Victoria. Because the water cart was the centre of gossip during WW1, the word also came to mean a rumour or false story. People thought Viv had made a mistake when choosing where to dig the well, but they had to admit it was in the right place, as he always had water.

The "Southern Cross" windmill pumped up a hundred gallons [450l] of water an hour with a good breeze. One day when working on the windmill he was knocked off by a vane, falling about thirty feet [9m] and splitting his head. Clytie drove him to the bush nursing hospital in first gear all the way as she had never learnt to drive. In time she learnt to drive, but only drove in the vicinity.

The "Southern Cross" windmill pumped up a hundred gallons [450l] of water an hour with a good breeze. One day when working on the windmill he was knocked off by a vane, falling about thirty feet [9m] and splitting his head. Clytie drove him to the bush nursing hospital in first gear all the way as she had never learnt to drive. In time she learnt to drive, but only drove in the vicinity.

Good Times and Bad Out West

Viv and Clytie organised groups for social and other activities such as cards. On their farm they had two tennis courts made out of ant bed gravel and a homemade concrete roller made of an empty oil drum and a pipe. They even had an umpire's seat and bush house, which were still there thirty years later. Everyone supported each other according to their ability. It was an unusual local committee that did not include Viv or Clytie or both and they were also active participants in other events in the lively little community.

Besides tennis there were plans for cricket and social activities were being organised. A one-teacher school opened in a room leased for twelve shillings and six. In 1927 a Memorial Hall was built and the first dance was held before the roof was on! Not much fear of rain! Church services were also held there. Those communities where people co-operated fared better than those where there was rivalry and suspicion.

Bert, Roy, Ken and Kathleen

Bert, Roy, Ken and Kathleen

Viv admired people and made everyone feel important, loved children, joked with them and showed his affection.

There was often afternoon tea provided by Clytie for a crowd of relatives. The bigger children played tennis or football. Eric made little manikins for Viv's younger children out of wire, wood and tar.

Viv and Beau favoured Aussie Rules based on a game which had originated in Ireland as Gaelic football. They both played Rugby League for Erigolia. Beau was very nimble, and it "took three opponents to hold him." He was popular with everyone but the other team.

In the dry weather all the cows died and Bill got goats for milk for the children. But goats were a lot of trouble and were not successful. Vi and Bill Glasgow left their farm in the care of a share farmer, and moved to Rankins Springs where Bill and a friend opened a general store in the main street. Bill managed to acquire a vehicle called a "half ton truck" (similar to a utility) probably a second-hand T model Ford. When Bill bought this vehicle there was no requirement to hold a licence. When he came to the first intersection he forgot which pedal was the brake, and had to make a hasty left turn and drive right around the block.

In 1926 there was a telephone exchange, the only subscriber being Glasgow number RS1 (Rankins Springs 1). Soon afterwards a new storekeeper held a fancy dress ball to celebrate the opening of another store.

Ida with Margaret and David

Ida with Margaret and David

Bill started a stock and station agency, and was also an agent for Sunshine farm machinery and "Southern Cross" windmills. As a form of advertisement there was a windmill in the backyard. Bob and Nancy climbed the struts, and played around a shed where petrol was stored. The produce he stocked included rock salt, which the children licked. His friend left the store, and later Bill sold the shop and kept on the agencies, sold farm machinery and was an auctioneer. He was never on the farm again. At times Charlie and Ida Johnston worked on his farm living in a lean-to through which the goats walked.

On their farm Viv and Clytie were struggling to make ends meet especially when the price of wheat fell to a shilling a bushel. When Viv was hospitalised in Griffith with bowel obstruction, peritonitis and suspected diabetes, and to Prince Alfred Hospital with stomach ulcers, Clytie had to run the farm and the household with the help of the children and the family. By now Bert aged nine was learning to harness and drive horses, drive a car, tractor and farm machinery and milk cows. At times Clytie had to do heavy work.

When times were good Viv had a remittance man on the farm, and a girl working as housemaid and mother's help for five shillings a week and keep.

At Erigolia there was a disastrous drought and no harvest at all for Viv. He and other farmers of the district went on a deputation to Minister Buttenshaw, without success. Without rain there was no grass and not even many rabbits for the pot. Brown mud in the dams cracked and curled up and the children called it chocolate. Early in the New Year the drought was broken by a flood, with seven inches in one night, which marooned visitors. The resultant harvest was good, but the price was only four shillings a bushel.

Ken, Bert, Isobel and Kathleen

Ken, Bert, Isobel and Kathleen

When Clytie was due to have her next baby she went to Griffith Private hospital forty-five miles away but once again the baby was stillborn. Their second son Roy contracted staphylococcal pneumonia at the age of seven. Such serious illness was a great source of fear to parents. After several weeks in hospital, he was the first of the grandchildren to die. It was found that they had been trying to drain the wrong lung. Clytie attended séances to make contact with Roy. Beau once took her but felt uneasy and would not go again.

The Late Twenties in Sydney

Back in Sydney, Rita's fiancé, Harold put electricity on at KY. The gas iron was replaced. Electricity had to come down from the ceiling, as the internal walls were solid brick, plastered, then polished to a marble-like finish. Cord-operated electric  lights and gaslights were both used for several years. A ceiling “rose” was put in the hall around the light. In his spare time Perce built a lean-to bathroom at the back of KY with an iron bath and chip heater. A gas stove was installed in the room that had been added by a builder in 1916, which became the kitchen/ laundry with the copper and cement tubs still in it. The original oven with a mantelpiece was still in its original position in what now became the dining room. It was used for storage. The transaction with Starr-Bowkett twelve years earlier had enabled them to obtain these luxuries.

lights and gaslights were both used for several years. A ceiling “rose” was put in the hall around the light. In his spare time Perce built a lean-to bathroom at the back of KY with an iron bath and chip heater. A gas stove was installed in the room that had been added by a builder in 1916, which became the kitchen/ laundry with the copper and cement tubs still in it. The original oven with a mantelpiece was still in its original position in what now became the dining room. It was used for storage. The transaction with Starr-Bowkett twelve years earlier had enabled them to obtain these luxuries.

Vern and Billy

Vern and Billy

At university Perce and others wrote and acted a play or mask. Perce played the parts of Knowledge and Wisdom, attendants of "Alma Mater". In 1926 he had gained passes in Latin, French and Philosophy and a distinction in English, and was now studying History, English and Psychology.

There was little contact with Vern, Mary and Margaret Hyndman who lived on the North Shore at Mosman. They sent their son Billy to Tudor House Prep School at Moss Vale. There would be no more children. On one occasion when Annie was visiting them, and enjoying one of Mary's beautiful meals, Billy had a lapse of table manners and Mary was mortified. Everything had to be perfect. Another time Mary had served a delicious sweet, and her mother had asked Annie if she would like more, which she did. Coming back into the room Mary said to Vern that she was embarrassed recently when he had accepted a second helping when they were visiting. "You never accept a second helping when visiting," she said. Annie in her usual forthright manner said "I only took another helping because Mrs Hyndman pressed me." She did not enjoy these visits and did not go often. Her idea of etiquette was based only on consideration for others.

Mary and Billy

Mary and Billy

Even as a boy Billy was an individual with independent ideas. Annie heard that the boy had an accident to his eye. Apparently he was in a tree at school and was hit in the eye by something thrown by another boy - it was not clear if he was reading in the tree or had climbed up to retrieve a football, or whether the other boy was pretending his stick was a javelin. There was no obvious injury, but it became apparent that something was wrong so he was sent home. If he could be kept absolutely quiet for three weeks the doctor hoped that the eye fluid would not be lost. A family friend, Joyce, who was a trained nurse, was contacted. They did their best to keep him from activity, but it was no use, the fluid had been lost and with it his sight in that eye. By then his father was working for Atlantic Union Oils, was on a comfortable income and had achieved some "status".

Nearby lived a family who had lost their eldest son at Poziere and whose youngest son was Gordon Leslie Melville, born in England, came to NSW aged seven, always known as Don. He and Gordon Louis Smythe known as Beau, became friends and had many friends in common. They were the same age, were of similar slim build and fair colouring, both liked Nellie Potter and both liked the beach. In fact Don had joined Ramsgate surf club, although there was normally no surf, only a swell when the conditions were right.

Don frequently worked in the country as a boiler maker. Beau often worked in the country doing any kind of work.

Don and Beau

Don and BeauAt Easter 1927 Don went with a family member and friends on an excursion on a launch “Bronya”, based at Cooks River. They were returning from Kurnell late in the afternoon when a very severe storm arose, the worst in 50 years. The vessel was eventually blown on to the breakwater on Cooks River. Nobody survived although some of them took their clothes off. Don’s body was not found immediately. The news was widely reported. It was a major disaster to the whole community. The Melvilles presented a silver inkstand to the young constable whose unfortunate duty was to attend. The event left a permanent impression on the young Smythes.

The next month even more newsworthy was the fact that the Duke and Duchess of York, Albert and Elizabeth came to Australia to open the recently completed Parliament House in Canberra. Their daughter Princess Elizabeth was a year old.

Harold bought a block of land from a market gardener at Bankstown, "the coming suburb", eleven miles west of Sydney, thirty-five minutes by train. The block was a mile from the station, which was the end of the line, but an extension to Regent's Park was under construction. The block had belonged to Harold's friend's father, who was now getting old and wanted to subdivide. It was an area of market gardens, house cows, chooks (poultry) and horses. The block for sale was eight times the average size, 480feet by 100feet [145 x 30m] for £100 and although it had been cleared of most of the big trees some stumps were still in the ground. A small creek had been diverted into a drain along the boundary. Like many other areas it was not sewered and the few houses all had tanks for water. Harold decided he would have town water as well as gas and electricity. Very modern!

On 15th October 1927 Rita and Harold had a quiet wedding at the Presbyterian Church, Kogarah. As her own sisters were too far away Harold's sister Rosa was Rita's bridesmaid. Only the parents and a few close friends were invited to the reception at KY.

For their honeymoon they travelled to Dorrigo on the motorbike and sidecar, which Harold had fitted out for a passenger, fording creeks, crossing the bigger rivers by punts, camping out at night. They saw the place on the Bellinger River where his father had been born. On one occasion Harold ran out of petrol and a farmer's wife gave them some out of her iron.

Soon after the marriage, Rita went with her brother Perce to the wharf to meet Dorrie and Betty on their return from England after a year and a half. Perce had to sit for his second year English exam at the university that day. He waited and waited until he could wait no longer and still the formalities had not been completed. He had to leave, and got to the university arriving just as the doors were being shut. Rita was left to explain to Dorrie. After the exam, Perce threw his four-year-old daughter into the air as he greeted her. In between studying he had made her a little table and chair. When the results came out, they learned that he had topped the exam, and had passed in his other subjects. Next year he planned to do English honours, Education and Oriental History for his Bachelor of Arts degree. He and Vern were the only ones with tertiary qualifications.

For a while Perce, Dorrie and Betty all lived at KY and Betty went to Miss Dillon's preschool where she soon learnt to read and write a little using a slate. While there they felt a tremor, which they learnt, was a major earthquake in Napier, New Zealand, with heavy destruction and loss of life. Betty had a wax doll but never played with it. She always had a leaning to do boyish things and was not discouraged by her parents. She decided she wanted to be a sailor, decorated her bedroom to represent a ship so that she could play at being a sea captain, read a lot of "sea" books and knew all about sails and rigging at a young age.

Annie had kept up the investment in Starr-Bowkett which Bert had started and when money became available Perce and Dorrie were able to borrow £400 to buy a house around the corner from KY in Ramsgate Road, next door to a house in which Nurse Armstrong, a trained midwife, delivered babies.

At Bankstown, Harold had built a large shed in which they lived, divided into two rooms with the furniture he had made. Water and electricity were laid on. With the help of his father and brothers, Harold built the house, borrowing £400 from the bank, to be repaid at £1 a week with rates £2 a year. He was energetic when interested in a project and very proud of his beautiful inlaid woodwork and other practical skills. The Smythes found him reserved and uncommunicative, but Rita was a good listener and he became expansive.

There was a gas stove, an ice chest, a tap but no sink, a dresser for china and cutlery above a "safe" to protect food from flies and ants and a large table in the kitchen, a chip heater in the bathroom, a fuel copper and cement tubs in the washhouse. In the dining room were a cedar table, a sideboard, a gramophone and sewing machine. The bedroom contained the bedroom suite that Harold had made. Happy newlyweds!

Although there was no billabong, only a creek diverted into a drain, Rita called the house "Billabong" and got a nameboard made and hung it on the house to remind her of Jerilderie her birthplace on Billabong Creek, and the "Billabong" books she still enjoyed. In the most recent book, Norah had married Wally, her brother’s best friend.

The Depression in Sydney

In January 1928 Eric and Ada had a son whom they called Gordon after Eric's youngest brother. As a baby he had a fall in a Ramsgate shop from his pram onto his head. A friend of the family who had been in the shop, called later at Dorrie's to enquire after him. At that time Dorrie had not heard of the accident. When the family noticed some signs of retardation they remembered the fall.

It was suggested that Annie should have an operation on her leg, but she said that she was used to it by now. She mainly lived alone although there were plenty of visitors. Only Gordon her youngest son remained unmarried and he lived out west. Nell was proudly wearing his diamond engagement ring.

At this time the Sydney Harbour Bridge was being built. The Illawarra Line was being electrified and trains would soon run from Central to St James as the first Stage of the Underground. There was great political unrest because of the looming Depression, and the amount of money the scheme cost. Slums and other buildings had been cleared for the Underground and the approaches to the bridge. There was plenty of argument about whether it was money well spent.

Electric trains were cleaner and quieter than the dirty steam trains, which were not popular. A serious tram accident had occurred at Ramsgate with the driver killed. The engine overturned and three carriages, fortunately empty, broke loose. Trolley buses were suggested. A meeting was held in the Ramsgate Picture Palace in May 1929 to urge the speedy electrification of the tramline. A petition was collected.

Annie had a strong feeling for the underdog, but also believed that people should be independent and help themselves and each other. One of her interests was in Douglas Social Credit and she subscribed to a paper explaining the philosophy. Started in Alberta, Canada, the scheme apparently worked well in a rural community where people knew each other, and could help each other financially, knowing who was reliable.

Social Credit Parties believed that Depressions were caused by a shortage of purchasing power. Workers had been replaced by machinery, which produced more goods, but those unemployed could not afford to buy them so the government of a country should create credit. Others argued that the system would cause inflation and devaluation and increasing instability.

In 1928 Perce had got his degree with second class Honours in English and passes in the other subjects, the only Smythe to get a University degree. The following year he borrowed money to finance getting his Diploma of Education, studying Principles of Teaching, Education Psychology, Practical Test and School Hygiene at Sydney’s Teachers College recently built in the university grounds. As an ex-serviceman he got a loan on very low interest.

Difficulties

After graduating, Perce had a mild breakdown. He was helped by family support to come to terms with his problems mainly caused by the after-affects of the war. He began writing Latin translations, which he published himself.

The negotiations to buy a house were finalised when Perce got a job teaching English at Barker College, near Hornsby so they moved and rented out their house in Ramsgate Road, which they had called "Juniper" because Perce had proposed to Dorrie by a juniper tree.

Harold had been working at the railway workshops at Chullora, near Bankstown. On the principle of last on, first off, he lost his job when the stock market collapsed and the Depression began. He and Rita went to Galong for a couple of years doing general repairs, electrical and woodwork for his cousin and odd jobs in the district. They got into arrears with house repayments, but could do nothing about it. As nobody had money to buy, the bank could not sell the house. About this time Harold became a Jehovah's Witness.

After travelling around looking for work for two years Harold decided to go back to Sydney and they were able to walk back into the house, which had mostly been empty and take up the repayments to the bank as if they had never been away.

Eric and Gordon

Eric and Gordon

For a while Eric had lived there after separating from Ada. Eric decided to go back to Ada who lived near Bankstown. From time to time he arrived at "Billabong" looking for a bed for the night. One day when he went home he found his young son quite distraught. When he calmed down a little he kept saying "Boy mustn't go out in the wet". Ada always called him "Boy". On this occasion he had apparently gone in the mud and Ada had become frustrated with him and lost her temper. Eric was very concerned about his son as he felt that Ada was inconsistent in her handling of him. She let him chase ducks around the yard in the blazing sun, then yelled and smacked him for some trivial thing. Eric was fond of Gordon and thought he should be treated with firmness, patience and love. He was convinced he would become more manageable. Eric was in a dilemma. What could he do?

In 1931 Eric went to Erigolia with some furniture taking three weeks in a spring cart, having again separated from Ada who had the support of her family. Although Eric and Ada had serious problems divorce was unthinkable. He stayed for about a week then decided to go back to Sydney with the cart. The children at school saw him pass, going east, but he changed his mind, left the gear with Viv and went by train. In Sydney Eric drove a taxi also a bread-cart, and was involved in an accident, resulting in facial injuries and a stay in hospital.

During the early years of her marriage Rita had had several miscarriages. Her heart condition was getting worse; she got breathless after any exertion, but never complained. For a while Harold worked at Kogarah repairing generators, starters and magnetos for a friend who owned a service station. Finally he was able to get back to the Chullora Railway Workshops.

Perce's nervous system found it a great strain to work in a hectic classroom. As the job at Barker College was not secure and he was the last one to be employed, he left at the end of the year, not waiting to be retrenched, and got a job at a private coaching college, at first full time, then as the economy became more slack, half time and quarter time. He had a small regular income from his war pension. Finally he conceived the idea of setting up his own private coaching college, and writing educational books. At first he sat in the office for six weeks in Bligh St, Sydney with a telephone (B4495) with no enquiries. This gave him time to begin to write books as aids to students. He wrote translations of the Latin texts set for the Intermediate and Leaving Certificate exams. Later he went on to write Guides to the Study of the Shakespeare plays and other English texts which were set for the exams. These sold well and became widely used by students and were known as "cribs".

Betty, David and Margaret. KY

Betty, David and Margaret. KY

Perce, Dorrie and Betty had moved into "Juniper", their house at Ramsgate, next door to Nurse Armstrong's cottage hospital. Perce’s first two pupils at the college were her son and his friend.

Perce wrote a little book "A Simple Remedy for the Depression," giving his ideas about the economy. Later on he turned to aids for students of French. He was able to repay the money he had borrowed to get his DipEd, the only one at that time who had done so, which they felt was sad: a kind-hearted man loaned money to ex-servicemen in good faith, and some made no attempt to repay it.

Betty went to The Park School (Ramsgate) and Sans Souci School. When Betty went for a holiday to her Auntie Rita at Bankstown she was at first homesick, but decided she might as well enjoy herself and was never homesick again in her life.

Soon afterwards Betty had a very high fever, which they thought may have been rheumatic fever. When the doctor came, he saw her running around and said "She's all right. It's not rheumatic fever." Years later she was to get endocarditis which indicated she had had rheumatic fever at one time.

Nancy, Robert and Margaret

Nancy, Robert and Margaret To await the birth of her fifth child, Vi came to KY with four young children. Nancy who was used to a lot of space and freedom went to Rita's for a while and had to learn to be quiet when her uncle came home, as "Uncle Harold doesn't like noisy children." Nell, Beau’s fiancée minded Hazel for a year and enrolled her in Miss Dillon's preschool.

After the birth of Bill junior, Vi returned to Rankins Springs, with the baby and Colin and Hazel, leaving Nancy aged six and Bob aged seven in the care of Annie for nine months, during which time they attended the Park School. Very strict with the children, Annie was always fair and never unreasonable. She took them into the pantry and showed them a strap hanging there. If they disobeyed she could not run after them, but threatened she would use the strap. It was never resorted to, but she had laid down the ground-rules. Nancy was also shown the gas tap and warned that it must not be touched. One day her curiosity caused her to forget the instruction. She realised her mistake and was relieved not to be punished.

Billy, Margaret, Betty and David

Billy, Margaret, Betty and David

KY was a place to go whenever problems became a crisis. Annie always coped with whatever number of people descended, maintaining control. The housework was always up-to-date and efficient routines were maintained. None of Annie's girls tried to keep up their mother's standards in managing their households. Not being robust, Rita tried to take things easy, Ida worried and Charlie helped her with some chores. They had different priorities, especially Vi who was quite relaxed about housework and mealtimes. Annie said to Dorrie who shared her views on housekeeping, that she was disappointed that none of her daughters was as tidy as they had been brought up to be.

Depression Years Out West

During these years cloth was available from the Police Station for people who could not afford clothes. There was a horrible mauve check for the girls and Charlie was proud that his children never had to wear it. He was often away from home working on the roads on what was known as ‘relief work’, and this was better than being on the dole. He sometimes had a long way to come home, but always tried to be there to see that the wood was chopped and things maintained for Ida.

Finally Charlie gave up farming at Rankins Springs, sold the farm and took Ida and the two children to KY. As had become a habit, on every trip between Rankins Springs and Sydney, they were met at Bowral station by Charlie's sister, Effie, who brought food and drink to fortify them for the rest of the way. Margaret went to the Park (Ramsgate) School. On one occasion Ida and the children visited Rita at Bankstown and while they were there Ida became ill and they had to stay. Before they could go home Margaret and David caught measles, fortunately they were not very ill. About this time, Norah of the “Billabong” books had her first baby. Much to her disappointment Rita had several miscarriages.

Billabong

Billabong

After a while Ida and Charlie and the children went to Shellharbour where Charlie tried dairy farming and they visited the Kiama blowhole. Charlie needed help on the farm as the milk HAD to be ready promptly by the roadside for collection. The unreliability of hired help worried him. The whole idea caused too much stress.

Ida was sick a lot and had to stay in bed. When she was well she read stories and poetry to Margaret and David, and taught them Irish and Scottish songs. She imparted a love of music, literature and poetry.

Later they went to Camden where Charlie grew peas. There was a huge persimmon tree near the house, and styles over the fences. They were still waiting for the money for the sale of their farm at Rankins Springs.

Growing Families

When they had not been able to acquire the real thing, people experimented with improvised condoms made out of material. The story was told that a new doctor came to the Griffith district who had a new method of birth control. The exact details of his revolutionary method were not explained to the next generation, but the result was that a number of new babies were born to the settlers, many of whom already had several children. Later Nancy overheard a conversation on the subject and asked "Why do they have babies if they have enough?" and was told by Granny Smythe "When the doctor comes you MUST accept the baby."

One day Beau came in from the paddocks to the Glasgow house very excited and full of talk about the publican at Rankins Springs who had a Tiger Moth (a two-seater aeroplane) and occasionally flew from Sydney in it. He was giving “joy flights” and Beau had parted with £1 for the experience.

When Viv and Clytie's son, Bert, the oldest Smythe grandchild, was about ten, he developed a mysterious wasting illness, which was eventually diagnosed in Sydney as due to a hydatid infection. Lumps the size of tennis balls were removed from his abdomen in a history-making operation, which left a weakness in the muscles and scar tissue and hernia. Others with the same problem died, but he survived. Viv had to go back to the farm and after a while so did Clytie, leaving Bert in the care of his MacPhee grandparents. He spent ten weeks in hospital and then five months attending the doctor. The family believed his recovery was due to diagnosis and good care from the doctor.

At Erigolia Clytie was due to have her next baby. After breakfast she walked along the track leading to the Bush Nursing Hospital. At three that afternoon a phone call announced "a boy" named Clyde after the doctor who had saved Bert. Even after the arrival of her little brother, five-year-old Isobel continued to be called Bub.

One day Viv was walking to town with Bert and they were talking about schooling. Bert attended the local school but did correspondence sheets for arithmetic and geography in the one-teacher school. He had a fragmented primary schooling, sometimes he was at Erigolia, sometimes at Pennant Hills but he always managed to do well. He calculated that he would be fourteen when he completed high school. As there was no high school nearby and sending children away was a fantasy for people like them, Viv told him that it was unlikely to happen. Viv had had to go to work at a much younger age, and had to educate himself by correspondence.

He often recited poetry, passing on his love of literature sitting in front of the fire at Erigolia - Poets Scott, Byron and Macauley including ‘Horatius at the Bridge’ from ‘Lays of Ancient Rome’. Traditional British values and a tolerant Protestant religion were part of the atmosphere.

By now Bert could do some butchering of chooks, rabbits, sheep, small pigs and cattle. His father taught him to use a rifle and his fists on the right occasions. In his turn Ken learnt similar skills, the little girls helping with the housework and looking after baby Clyde.

The Curries of Myrrhee

Bobby Currie had saved his money and bought a small farm at Grong Grong to grow wheat, also a stallion racehorse from which he bred. He was doing well and was very involved with horses, breeding, showing and painting them.

He had lived in two or three large sheds until he became engaged to a local Grong Grong girl, when he built a house with some unusual features. One day he found her wearing lipstick, a "modern" habit of which he strongly disapproved. Perhaps over this incident they had a disagreement and the engagement was broken off. In later years he was to express regret about "the worst mistake of my life". Also when Bobby had an argument with the butcher he had to go without meat for some time. He had a strong personality but was generally well liked; he would have a drink but was not intemperate. Although he came home to "Macrorhyncha" a couple of times a year in his pony and jinker and always loved the Myrrhee district, he had become a bit of a recluse from the family. Like some of his Smythe cousins, he enjoyed painting and drawing. He was an individual who had a plan to buy more land and breed horses, particularly Palominos.

His father Robert was forced to sell the property at Myrrhee as it was heavily mortgaged so he, his sister Lydia and the girls moved to Benalla and started again. They soon got work, the girls aged nineteen and seventeen in the town, their father as a carpenter in Mildura for Chaffey Brothers, who had started the famous irrigation scheme, later in Benalla for VicRail. Eventually Flora was employed by Holz Furnishings, making blinds and curtains. After a time Eileen became the book-keeper at the gas office and remained there for many years. As he was a competent carpenter Robert had no trouble finding work, and was never out of a job. Later the grand house he had built which had caused him financial difficulties, burnt down.

Lydia was a lovely kind, "soft'" person who had devoted her life to bringing up her brother's children and was then living with her brothers Robert and Arthur in Cunningham Street, Benalla. She had been careful of the money she had got from her father's will and a small amount still remained. She died of cancer and was buried at Winton Methodist Cemetery, like her father and mother and brother Rollie.

Sydney Harbour Bridge

Bert got through primary school and started secondary school by correspondence, sitting up the back of the classroom. Although he got a place at Yanco or Wagga High Schools, Viv and Clytie could not afford the hostel fees.

As compensation, they gave him £7 to go to Sydney to see the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Bert went to his grandparents' place at Pennant Hills and from there went to Hornsby School, repeated sixth grade and got a bursary to go to Fort Street the following year.

On 16th March 1932 Perce and Dorrie took Betty to see the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Fort Street School had the honour of leading a column of thousands of children over the bridge, before the official party. When Betty and her parents walked over it she could see the water between the slats and felt frightened. They stayed in town for the fireworks afterwards. Europe had its grand old buildings, The United States had its skyscrapers, and now Australia had the largest single span bridge, the highest structure in Australia. The pylon had a monopoly of views to the Blue Mountains. Tramlines were built strong enough for possible future trains to the north, which at the time ran from Milson's Point to Hornsby.

Back to Rankins Springs

Ida and Charlie went back to Rankins Springs to work for the man who had "bought" their farm but had not been able to pay for it because of the Depression. The Government had brought in the Moratorium Act to prevent people being put off their farms if they could not pay. The Johnstons camped on their own farm with the buyers. They lived in a lean-to at the end of the wheat shed during a mouse plague. This was very distressing and humiliating. It would be many years before they received a settlement and were not fully reimbursed. They were given no choice and had to accept an amount much less than what was owing. It was a long way from the school so Margaret and David did correspondence lessons from Blackfriars. Ida was a good and tolerant teacher.

Bill Glasgow became a Councillor of the Carrathool Shire and was elected president in 1932. The following year he bought a brand new Ford, the first of the streamlined cars, which was driven at the reckless speed of forty miles [50km] per hour, by the proud owner.

One day Beau arrived on a pony, to find that Clytie, with a load of children in her eight-year-old Ford, had hurt her elbow "cranking" the car. Beau drove the crowd home and later suddenly remembered the poor pony still tied to a tree. As he never got angry they were astonished to hear him swear.

Beau was working in the Erigolia area as a "stock and station agent". He was always nattily dressed, was good company and quite a livewire even a bit of a "show-off". All the girls at Rankins Springs set their caps at him or vied for his attention. Vi wrote to Nell that she had better not wait too long if she wanted to marry him. As a lad at Ramsgate he had said he would marry her one day. For eighteen years, since the age of twelve, she had been the unpaid housekeeper for her family and they did not want her to leave to marry. Nell finally decided to go west and got no support from her family.

Last Wedding

The couple planned to marry at St Albans in Griffith in June. Clytie made an elaborate three-tiered wedding cake. Nell saw it with only the almond icing and was dismayed at its plainness. Viv designed the cakes, which Clytie made and decorated. Hazel, aged about eight, was Nell’s ‘pet’ and attended as flower girl, young Bill was pageboy. Bill senior was to drive the bride to Griffith. As it was a very cold morning in mid-winter, the car wouldn't start and they were late. Bill was most upset and got agitated. Probably only Bill, Vi, Clytie and Viv attended the wedding.

Nell and Beau had a short honeymoon at Narrandera. Soon afterwards they minded the Glasgow children while Bill and Vi went on a holiday. Nell and Beau insisted that the children ask for food to be passed and were not allowed to reach.

All of the surviving eight Smythe children had now married. In contrast only two of the eight surviving Curries had married and both had been widowed.

Bill and Vi went on a trip to Victoria and took Rita with them for a break. She had been married for five years and had not managed to carry a child to full term. It was a rushed trip and they got to Benalla late in the evening.

Flora and Eileen lived with their father and Uncle Arthur in a simple house in Cunningham St near the railway, after having to leave "Macrorhyncha", Myrrhee. They wanted to show the town to the visitors. Benalla had grown to a town; Winton had not lived up to its early promise, being too close to the bigger place.

They all went to Eileen's fiancé, Walter's place to include him. As he was doing heavy work he had already gone to bed on the veranda. Eileen insisted he get up and they dragged him along with them. Walter felt that Rita was developing a religious fervour perhaps influenced by Harold who had been converted and become a Jehovah's Witness. Walter was "a gentleman", a very thoughtful person. Somehow he got the wrong impression that Bill Glasgow had been involved in the premature cutting of the Harbour Bridge ribbon and perhaps Bill did not correct him; never one to let the facts get in the way of a good story.

It was said that Flora looked like Rita, although a little younger. Eileen and Walter planned to marry the next year. Flora and Bobby were unmarried. Bobby was doing well at Grong Grong where he had gone after the disagreement with his father and where he was now a stalwart of the district. He had bought land, built a house and was growing wheat and oats and becoming interested in breeding Palomino horses. He also liked to show and paint them. Both he and his father were reserved unorthodox individuals, but Bobby was considered a popular part of the community, although his engagement to a local girl had been broken off. Walter found his future father-in-law Robert Currie to be a "difficult fellow", very clever and "strong" but not sociable.

Their maiden aunts, Allie and Fanny, still on the farm at North Winton continued the dispute with the Council.

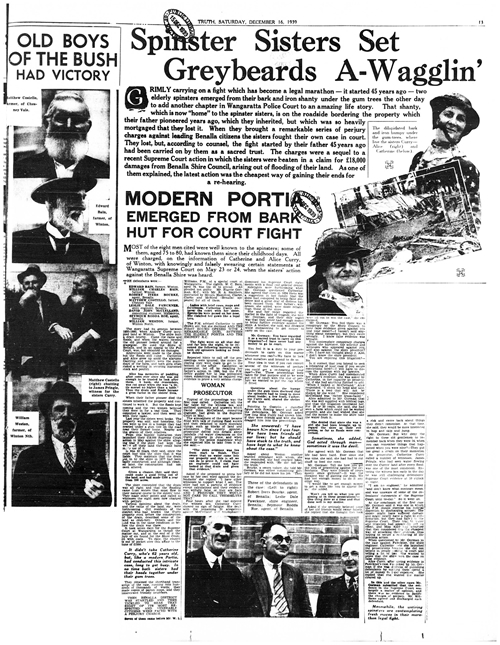

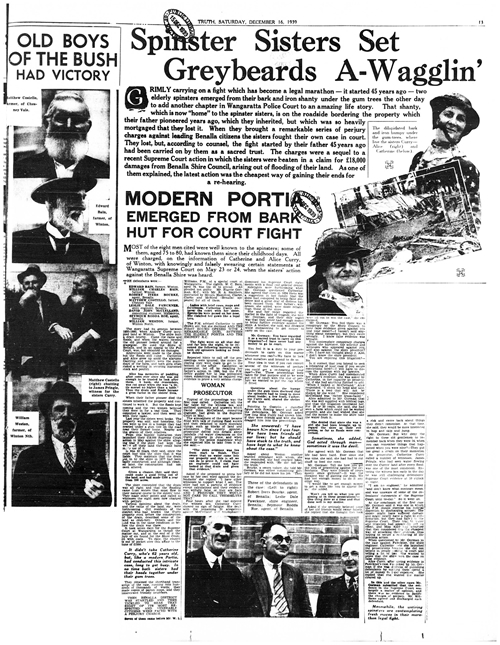

"Truth" Melbourne 16th December 1939 Page 13.

Spinster Sisters Set Greybeards A-Wagglin'