Chapter 20 MISS PUSS

Bright and early on Tuesday 27th January 1953, I dressed with care in my yellow cotton frock, cut my lunch and caught the train from Strathfield to Granville. The train was delayed, I hurried the half mile to the school and arrived just before nine o'clock. The Infants' Department was a two-storey building and some "portables" with a small asphalt playground. Hundreds of children in bright new or freshly laundered clothes, crowded into the area, their mothers looking over the paling fence until bell time.

I walked up to the main entrance and, trying to sound confident, introduced myself to the headmistress in her office.

"I am Miss Jackson," she replied. "Sign on here please. Are you an ex-student?"

I nodded, sensing a disappointment. Two more young women arrived and signed on before the headmistress ruled a red line across the sign-on book to indicate anyone else would be late.

"Come along to the staffroom," said Miss Jackson.

"It's a big school," I observed as we walked along the corridor.

"Fifteen classes and fifteen teachers. Six hundred children. Do you play the piano? Where do you live?"

"Until now at Pennant Hills. Now at Strathfield. I'm not much good at the piano."

In the staffroom the teachers were discussing their holidays and conjecturing about the teachers who had not yet arrived. About half the teachers, mainly the older ones, smoked in the staffroom which I found a little surprising. At college it was not affordable. I had too many other priorities, to spend any spare money on cigarettes.

We counted five ex-students, an unusually large number. Miss Jackson was dismayed. Of the others, a few were young teachers, some were mature women with grown-up families, one was about thirty and unmarried, one had a seven-year-old daughter enrolled at the school. The older teachers were not introduced by their Christian names as we young ones were. This distinguished us even further as novices of no standing with so much to learn for which college could not prepare us.

The toilet block was indicated and the key that teachers needed. No toilet paper was supplied, if necessary use your lunch bag or whatever. We brought sandwiches from home or an order could be written on a paper bag for a little shop across the road. Most of the teachers and nearly all the children brought a cut lunch.

At 9.30 the deputy rang the bell and the children lined up in last year's classes. The children in last year's second classes were soon taken to the nearby Primary Department. The first classes were promoted and had to go upstairs and down in an "echo chamber" six times a day which created a problem with noise, discipline and timing to avoid congestion and resonance in the area.

During the morning I minded the Kindergarten from last year, distributed the school milk, listened to their news and read stories until the children were taken to their new classes. In the afternoon I helped in the office with lists of names, to which we added the transfers from other schools and on which we noted the children who had not put in an appearance.

The next two days I helped the other teachers receiving the new entrants as they came, eager or tearful on their first day at school.

On Friday at last I was given my permanent class, Transition, a group of children who had been at school for a term last year and who were then about five and a half. It was presumed they were not yet ready for reading and did a lot of "pre-reading" and work to develop verbal skills - colours, shapes, "same" and "different" and other concepts. I was issued with enough books, pencils and scissors for my class, an old program and timetable to help work out mine.

The timetable had to be worked out around fixtures such as Assembly which involved the whole school and Scripture given by visiting ministers and volunteer scripture teachers from the various religions according to the enrolment forms of the children. If the family had no particular religion, they usually enrolled the child as Church of England.

Something had to be put into every space of the program for a five-week period. I spent most of my weekend working on it. There were stories, poems, speech rhymes (intended to help children with problems such as pronouncing "th"), safety, health, poetry, singing, art and craft (learning to use scissors to cut out and paste shapes which had been traced on to coloured paper by the teacher), physical training, singing and so on. What a bore! I didn't think my piano skills were suitable so Kindergarten teachers gave rhythm lessons to my class at three o'clock when their own classes went home. I later realised that with some practice, I was as good as most.

There had to be a bible story every week. I avoided stories like Abraham preparing to sacrifice his son, Isaac; Samson killing the Philistines; David killing Goliath and Joshua killing the Canaanites within Jericho. I had problems with Esau being cheated of his inheritance by his brother, in fact the idea of one son inheriting everything was a problem. I omitted Adam and Eve altogether as I had realised that the story, similar to those of all the other cultures I knew of, was completely earth-centred having arisen before the "solar system" model and long before powerful telescopes. In my program I put down Noah and the Ark but I thought it rather fantastic to believe that two of every creature could be literally taken into the Ark with enough food and water to live peacefully together - even just the warm-blooded animals, the thousand or so I knew of. I had just read "The Overloaded Ark" by the naturalist Gerald Durrell with wonderful illustrations, about the huge number of species to be found in a limited area of the Cameroons. The very funny books with a very serious message were to become among my favourites. The idea of natural selection continually fitting a species for its particular environment really made sense. My knowledge of the rich world around was expanding, but the reality of my working life was that I had to fill those spaces in my program from a specific list.

On Monday, my first real teaching day, I took my class to my room where I had drawn a picture of a fire engine on the blackboard. My class sat on the mats as instructed and looked at me with eager anticipation. I gave my prepared lesson on the danger of lighting fires.

During the day a little girl had toothache, someone spilt a bottle of milk and Dennis was sick twice in the classroom. Teachers had to clean up any such mess, there was no-one else to do it. The school had a small supply of spare clothes for emergencies. Apart from that all went well. I felt satisfied I had made a good start. Full of enthusiasm I stayed back until five o'clock to arrange my room and do some work. Two boys went home after school and set fire to the vacant block next door. Not the intended outcome. So much for didactics!

Playground duty was always very busy. In fact it was a chore, especially in the overcrowded areas, all asphalt. Three teachers were needed to do duty at any one time. Never a day went by without first-aid being required to remove splinters, bathe skinned knees or worse.

I was the product of a disciplined and competitive system and I saw my first duty to keep order and my second duty to impart knowledge. Classes were too big to allow for much individuality or creativity and these were not seen as desirable. Generally desks were placed in rows, children had to sit quietly until told to do the next task, decided by the teacher. If the teacher was not standing in front of the class "chalking and talking" and believing she had everyone's rapt attention, then she was not earning her money. There was little room for incidental learning only directed tasks, most of which were for the whole class. Teachers had to teach rather than inspire children to learn.

With young children it is less a matter of knowing the subject matter, rather having insight into their thinking, being able to "read" the expressions on their faces, knowing what their questions really mean, finding a way to answer questions in a way they will understand. There is no point in carrying on with a prepared lesson when you have "lost" the class. Learning should be fun and "engage" the child. No matter how tired the teacher, it is necessary to enthuse in every lesson as if every fact is exciting and new. As time went on I became more relaxed about discipline and realised I could influence my class more by motivation and encouragement than punishment. I tried to find time to listen to their individual interests, usually possible only when on playground duty.

Most days ended with a quiet story. At first I told "The Three Bears" with suitable growls and expression followed by stories chosen from one of the books which the children brought. "Snugglepot and Cuddlepie" by May Gibbs with delightful bush characters and original illustrations, became a favourite. More children's books were becoming available, many of them with beautiful illustrations. The "Twin" books such as "The Eskimo Twins", "The Dutch Twins" and "The Cave Twins" were read as a daily serial, the stories and black and white illustrations by Lucy Fitch Perkins showed a whimsical sense of humour. The children tended to confuse the Stone Age with dinosaurs, who had lived millions of years earlier and found them more captivating.

I began to find the skill and reward in dramatising as I read in a way to engage the children and to overact the parts if necessary.

At the staff meeting extra jobs were allocated. Someone had to be Federation Representative, collect for the Red Cross and so on. My job was the school banking, which was done every Monday morning to encourage children to save. The amounts, usually a shilling had to be written into the bank books and at the end the coins counted and wrapped in paper as shown by the bank clerk who came to collect it. It was time-consuming but considered a valuable lesson for the children.

Once a week the storeroom was unlocked by the deputy and we could collect pencils, books, master sheets for the duplicator, art paper, coloured paper for craft, paper-weaving mats, scissors. Our requirements were written in a book. If too many pencils or other items were requested, questions would be asked.

The only equipment was a spirit duplicator. A stencil had to be created on special paper. It produced enough sheets for a class if well made. We also used "jellypads" with a firm jelly set in a tray a little bigger than a page of an exercise book. The stencil was done in reverse and placed on the jelly, then transferred to each child's book, one by one. No time could be wasted as the stencil began to sink and disappear into the jelly.

There were very few ready-made aids or charts and we had to make our own. The backs of old calendars were most suitable for charts as they were sturdy and had a built-in means of hanging. We used pens and Indian ink which was clearly legible, but impossible to correct if any error was made. The only solution was to start again. We learnt to be very careful. And I learnt to do the accepted style of printing becoming quite skilled and quick. There were a few large pictures which we used for "picture talks", encouraging children to observe the details and draw appropriate conclusions. Learning should be fun and "engage" the child. Boring systems reduced the desire to read and the pleasure of books. Much teaching was still by rote although we had learnt at college that children (and adults) needed to understand what they learnt. Even Einstein found that recitation was "mumbo jumbo", a "turn off".

After years of study and living on an allowance, my first pay was £10, our male friends earned about £12. We did not see any injustice in this as the boys usually paid for us on outings and when they married they would have a family to support. High School teachers, university graduates had studied longer and earned quite a lot more but we did not feel envious. Society had accepted that women were part of the workforce, the lower wage meant that they were sometimes favoured in employment and some men complained that women were taking their jobs. There would be no going back. Men would continue to lose jobs in what had been considered "men's work", especially with greater mechanisation.

Our pay was always by cheque and we cashed at a store such as David Jones in the city or we could arrange for cheque accounts. Within a day or two I laybyed a raincoat and swimming costume. Although two-piece costumes were coming in, I chose a one-piece yellow cotton "shirred" garment which was elastic but not saggy. I needed a new fountain pen. One with a gold nib would cost 19/6 (almost a pound), a platinum pen was 7/- (about a third) which was more affordable if not as long-lasting. Rent for my room was £2.10, food cost me about the same, leaving about half for fares, clothes and other necessities. I felt enormously rich, although I had never FELT poor, only challenged. No longer did we get travel passes to take us to school or College and had to pay full fare and of course any outings had a cost. Shoes were also a major expense. Most of my clothes I still made myself, some of these were now nylon which was fairly new on the market, a bit more expensive, but lasted longer and needed no ironing, a big advantage. I continued to make Mum's clothes, but her needs were few. For Bill I was knitting a blue jumper, using bluebell crepe wool and an interesting pattern. I also experimented to create knitted or crocheted tea cosies with wool left over from other things, using novelty patterns to look like dolls and animals.

A salesman coming to the school persuaded me to take out an insurance policy. The Federation had already suggested to us that we needed to protect ourselves from being sued, now I was told I needed protection from accidents. The most dangerous thing I did was bushwalking. "If you don't need to claim, you can go on a world trip when you are forty." I didn't want to wait until then, but he was persuasive and I signed up. I spent most of my money as I earned it. Every pay brought some advancement. But some was always put aside for the "rainy day" or the treat. Sometimes I splashed out and bought something with no health benefit, but mainly stuck to chops, eggs and vegetables which I was used to. And if I was out with my friends we could afford an occasional milkshake at a milk bar. Mine was always chocolate flavour.

We could afford to go out more often and not always to the cheapest seats. Musicals took the place of romantic novels for me. "Oklahoma", (Rogers and Hammerstein) which I enjoyed very much, had created a record by running for five years in New York without an empty seat. "The Student Prince" (Sigmund Romberg) was also very appealing. Sometimes we went to shows at the ornate State Theatre with its chandeliers, marble and gold statues. It could also show films, hold concerts and stage shows. Sometimes we went to a five o'clock film followed by a Chinese meal or at least coffee and raisin toast at at a cafe such as Repins. A night out would include a meal beforehand if it was a special invitation and maybe a box of chocolates.

My class and I grew to know each other and I took great pleasure in the progress of my pupils, development and their personalities. It was quite a challenge to me to memorise all the names and put the right name to the right face, not something I found easy. At first it was more by their behaviour or clothes or where they sat that I recognised them. Quiet, well-behaved children were easily overlooked.

Transition Class

There was Cecil, mostly barefooted who announced one day in news:

"My dad is going back to the other woman he lives with. My mum was crying while she did the dinner."

There was David with red hair and freckles, Peter from Scandinavia who was NEVER perturbed, Darryl with the beautiful brown eyes who had told his mother his teacher's name was Miss Puss and when she expressed surprise said "Oh no I think it's Miss Kitty", Billy who looked at me through his eyebrows, Vivienne objected loudly when she lost a handful of hair one day and John who sat on the mat next to her perfectly innocent-looking with a handful of hair the colour of Vivienne's in his pocket and Wendy with a mop of curly hair whose straight lines in her books always turned out to resemble her ringlets, and Raymond, from a family of eight children who announced that the dog had eaten their toothbrush.

One boy had only one outfit which he wore every day except wash days when he stayed home. By the end of the winter his bare bottom was visible and he acquired another outfit. Was there nobody in his family who could have mended it? When I was only a year or two older than him, I could have produced a neat darn.

Bushwalking continued to be a major activity for me with some caving when I started to go out with Ron, a keen speleologist. He used to organise most of the trips we went on and this usually involved permission to explore unopened caves and a vehicle to take us and the club equipment; aluminium and rope ladders, carbide lamps as well as the normal personal rucksacks, sleeping bags, tents, photographic gear etc. He was the first smoker I went out with. Most of my family was non-smoking and few bushwalkers smoked, but joked about smokers' coughs and "another nail in your coffin". It was an unwritten law that nobody should smoke within the cave system but Ron was not strict in this.

We read books about "potholing" and others by Norbert Casteret, a French speleologist also books on cave paintings by prehistoric man where explorers 20,000 years later found evidence of art work. Caves certainly displayed more than formations.

As one of the few without a suitable camera I was generally the victim. Malcolm even ran to colour film.

"Sit up there on that rock and look at the stalactite... A little further left ... yes, now just hold that while we set up the lighting and get focussed."

Then followed experiments with the various equipment. Sometimes all the photographers would open their shutters in the darkness and one would set off a flash which all could use.

Caving was less strenuous on my back as we did not walk far with all the equipment. I could help organise while the boys transported ropes and ladders.

One weekend we visited Bungonia Caves, near Goulburn and one at a time descended on a rope into the Drum Cave. It is shaped like a funnel, narrow at the top where it is possible to use your feet to steady yourself, then opening into a huge cavern. Going down was not too bad as it was fairly swift, but the ascent was slow and painful. There was a smell of bats and damp earth. I was the first to be raised being the lightest in the group. Those above pulled in unison and I rose a foot at a time and spun round twice. My headlight flashed round the cave walls. It would be better to ride up in darkness, so I decided to switch it off. The rope sling I was sitting in was a hard seat by the time they had lifted me 200 feet. I then added my pulling power to help bring up the next of the troglodytes, who had begun to think they were doomed to life with the bats.

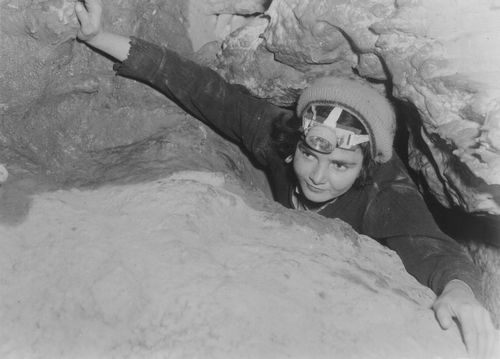

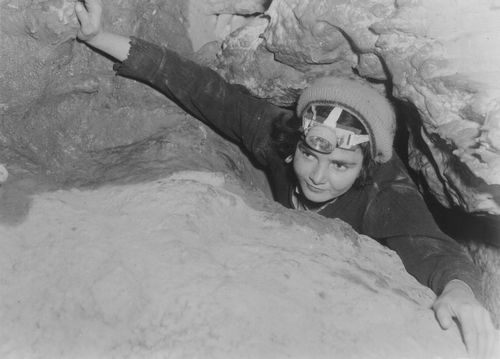

On another occasion at Jenolan Caves, Harry and Malcolm my old friends from Tasmania, were among the starters. Ron had hired a car for the gear. We spent the afternoon exploring the cave preparing for the fifty foot squeeze hole. By now we had learnt that this area was once under the ocean, as astounding as that seemed, and was very, very old in geological terms. Formations came from calcium carbonate which came from ancient coral reefs. Stalactites came from the ceiling, stalagmites from the ground.

In the Giant Squeeze Hole, which small people like me could wriggle through like snakes, Harry, all 6'2" of him, found that his red hair was several bends further on than his size ten boots. For a while it seemed that he might be creating another skeleton cave, of all who were ahead of him, because there was no other way out. Malcolm pushing from behind, gave him something to lever against and inch by inch he negotiated the passage.

"Thanks old stickos," he panted.

"I might be an inch shorter than you but I'm a size heavier," said Malcolm "so I'll chicken out this time. I like a bit more room to manoeuvre in. I'll look around here till you come back." In the narrow twisting tunnel, his voice echoed and re-echoed mockingly.

The second time through, Harry was more experienced and managed with slightly less anguish.

Squeeze Hole Jenolan Caves

Those of us who had holidays in May, mainly teachers, went by train at night to Coonabarabran, in the flat north-western plains, shared a taxi to Timor Rock and walked five miles or so to camp on a creek (upper reaches of Castlereagh River). The next morning we continued to Belougery's Spire, part of the Warrumbungles, where the others were camped. From the foot of the Spire there were magnificent views of the volcanic rim, rising from otherwise featureless country, jagged spires, domes and mesas, and echoes from the surrounding cliffs. In the following days we explored The Spire and Crater Bluff. Another feature was The Breadknife, formed by magma, plastic lava flowing through a crack thousands of years ago, a formation which rockclimbers liked to explore [no longer allowed]. From the rim in one direction was the coastal plain, in the other the western plain, resulting in prolific wildlife from both land forms.

The Breadknife, Warrumbungle Mts Aug 1956

Photo by Brian Petrie

On the return trip we collected mushrooms which had sprung up everywhere after a shower of rain, using our billy cans and hats. We cooked a proportion of them on hot stones around our camp fire and gorged ourselves, enjoying the rich savoury smell and taste but unable to eat them all. Finally we walked back to the road where the taxi picked us up as arranged to take us to the station to catch the train. At Mudgee we changed into a "dog box" and tried to go to sleep. I arrived home at 5am and went straight to bed and slept until 11. Another wonderful scenic experience, at the time not easily accessible to any but bushwalkers.

We got back to the news that Mount Everest had at last been conquered by the New Zealander, Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tensing Norgay. This was the absolute ultimate and to us a major event of the year, competing with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth as the news reached Britain that morning. Hillary immediately became an international celebrity and later was knighted. This was quite beyond any ambitions of ours although it was something we understood and some of our friends joined a group training for an expedition, climbing in the Himalayas. For each of us there was a different reason to climb a mountain but we all in our own way shared the experience. The term Sherpa came into our vocabulary, mainly when asking someone to carry something.

"Who was your Sherpa last year?"

About this time I read "Dust on my Shoes" by Peter Pinney trekking inexpensively overland from Greece to Burma. One day I would see some of those countries, even the Himalayas and experience other cultures, in the meantime I did so vicariously.

We had a holiday to celebrate Coronation Day and I organised a day of tennis to be followed by a visit to the Domain to see the fireworks display.

"It should be a good day, none of us over-serious about the game. You can leave your tennis things at my place if you like and we can go straight to the Fireworks Display," I offered the other girls.

After a good day of social tennis, some of the girls accepted my invitation to change in my room, before we met the others at the Domain where we sat on rocks to watch the display. The boys had to carry their tennis gear as it was unthinkable to invite them to change at my place.

"Well I'm glad the Queen has been so kind as to give us a holiday. But it seems ages since the King died, at least a year."

"I remember it exactly," I said. "I was coming home from Tasmania two days before my birthday. It's amazing but that's sixteen months ago."

After the fireworks we went to a cafe "a cheap and dirty" according to Harry, to eat raisin toast, drink coffee, relive our adventures, plan new ones, joke and chat. By the end of the evening I found I was getting hoarse.

The next day after croaking all day at school, I went to the Kameruka Club meeting, but as I was losing my voice and didn't feel well, I left and went home early. The day after I stayed home. The phone rang and I got up to answer it. Picking up the receiver I tried to recite the number. Nothing came.

The caller said "Hullo. Hullo."

I tried to whisper, but the caller could not hear so I hung up.

Another day off work and my cold was nearly gone, but my voice remained elusive. At the weekend I convinced myself that I was well enough to go on a walk to the Blue Mountains. Naturally I could not refrain from talking or singing round the campfire. My voice has never been the same since.

As I was required to have something for my class to perform on Empire Day, 24th May, I searched for something not too nationalistic and trite, eventually writing my own poem about the floral emblems of British Isles. (As remembered after 55 years and marginally more acceptable to my mother)

"A tribute to you now I bring

A bunch of pretty flowers are seen,

The rose of England

Bluebells, thistles both from Scotland

From Wales the daffodil

And from Ireland the little shamrock leaf of green."

My time was occupied after school hours, with regular visits to my mother, meetings of the clubs I belonged to, going to local Saturday night Town Hall dances, which were 50/50 meaning some "old-time" dances as well as quicksteps, fox trots, tangos, (my favourites), going to the pictures with Ron (he was invariably late), going to balls with Harry (Ron was one of the few who didn't dance), visiting my relatives and girlfriends and in between there was school preparation, sewing and knitting (a blue jumper for Ron) and occasionally some housework in my "digs". When my girlfriends' parents went on holidays they often asked me to keep their daughter company. I was back at Pennant Hills for a fortnight helping Cecily keep house for her two younger brothers (we taught each other to make gravy) and at Peggy's place for another fortnight. Peggy, John's younger sister was a librarian and had also been to Fort Street two years after me. She was passionately fond of serious music, especially Beethoven. I had met her at a Youth Concert, when John and I were at college.

So many of the bushwalkers and their friends and relations attended the Youth Concerts that we decided to get a group booking for season tickets, which meant some of us taking turns to queue up all night to get good seats in a block and get group reductions. The concerts, begun by the Australian conductor Sir Bernhard Heinze had become extremely popular. They ended at eight o'clock and we usually went afterwards for a shared Chinese dinner or had coffee in a not-too-exclusive cafe where we would not be thrown out for making too much noise. We were certainly not averse to trying new foods or activities. It was really great to have enough money to indulge in these luxuries, to see all the best films and get cheap seats for an occasional stage show, ballet or concert. A highlight was "Reedy River", the name from a poem by Henry Lawson, the story based on the 1891 shearers' strike, and involving the accidental shooting death of a little boy. It was a stage show devoid of any glitz at a venue equally devoid of glitz, over a grocery warehouse which had previously been the Australian Seamen's Union, in Pitt St near Circular Quay, Sydney. We heard the Bushwhackers' Band with "Click Go the Shears" by Alex Hood and many other "bush" songs. I remember the homemade rhythm section of a "bush base" (a large box with a broomstick attached and a single string to pluck) and a very tall "beanpole" playing the lagerphone (an instrument consisting of a strong stick, covered with rattley recycled beer bottle caps), a washboard and a carpenter's saw. Occasionally after a night out in the city we ended up at a night club in King's Cross, which was a little, just a little, daring, dark and seedy. I was also dabbling in opera, "Carmen" and "Madam Butterfly" as well as the latest from Rodgers and Hammerstein "South Pacific".

Cecily was less venturesome than the rest of us. John came up from Wollongong most weekends and he and Cecily and other friends sometimes went on picnics, between more strenuous walks. A year earlier we would have regarded this as a bit "soft". At one picnic John who weighed about twelve stone, was wrestling with a younger and smaller member and of course was getting the better of him.

"What are you anyway, a man or a mouse?" asked John, sitting on Ray's chest.

"I'm a mouse, I'm a mouse," he squeaked and was known by that name from then.

During the melee John fell on my basket and squashed my tomatoes.

"Look at what you've done," said Mouse. "Poor Dot. Everything happens to her."

"We've noticed that," agreed Malcolm. "But she bounces well."

Cecily had an electric sewing machine which was so quick and easy. Ron was going to put a motor on Mum's old sewing machine for me.

"Don't expect that old 'New Home' machine of your mother's to go like a new one. It would be much heavier for a start."

"Yes I know, but it will be better than a treadle and take less room. It goes like a chaff-cutter but better than nothing. At times I've had to do my sewing by hand."

Due to ever greater use of electricity, there was an ever-increasing demand, and many blackouts with power failures at Bunnerong. Many businesses had an auxiliary power source. Candles were always kept handy and many people preferred gas for cooking as being more reliable.

My brother asked me to lend him some money to buy a better motorbike. This was a new experience, having money to lend!! I wrote out a withdrawal form, but the bank doubted its authenticity and rang me at school. I convinced them that all was well.

A couple of days later, everybody I knew seemed to have rung me while I was getting my evening meal ready, Uncle Viv to say good-bye before going back to Rabaul, Auntie Dorrie to see if I wanted to go over tomorrow, and five others. At last I was eating, when a knock at the door interrupted again. Bill was there to show me his new bike. I cooked him something, then we went for a ride to Watson's Bay. He was at this time staying with dad's brother Bruce who was a pastry-cook and lived at Oyster Bay. Bill had a girlfriend, not too serious. When Bill repaid the loan, Dad borrowed £50 for a new truck.

I got plenty of invitations, but did not get seriously involved with anyone. Harry rang me regularly for a chat and sometimes to ask me to a ball or a party. I enjoyed his company very much but both he and Malcolm were working and studying part-time and neither was interested in nor had the time for a steady girlfriend. Pity. When there was nothing else on a Saturday night, there was always a dance at the suburban town hall and I often went with other girls. There were lots of quicksteps, tangos and waltzes as well as easier Barn Dances in which we progressed to meet all the boys.

In spite of all the rushing around and accepting every invitation so as to keep busy, there were often empty hours. There were plenty of ups and downs, hopes and bitter disappointments and lonely times when my school work was finished, library books read, no sewing or knitting on hand and the phone didn't ring.

The people where I lived were a motley lot and none of us belonged together. It was just a place to sleep when none of my friends' parents asked me to stay the night.

NEXT >>

Transition Class

Transition Class

Squeeze Hole Jenolan Caves

Squeeze Hole Jenolan Caves The Breadknife, Warrumbungle Mts Aug 1956

The Breadknife, Warrumbungle Mts Aug 1956