Chapter 12: “THE RED AND WHITE DIAMOND”

EXTRACTS FROM THE 24TH BATTALION HISTORY "THE RED AND WHITE DIAMOND"

These extracts cover the actions in which Viv (Capt E.V. Smythe) and his company were involved and his name mentioned. There is one paragraph about his brother, Lieut. P. E. Smythe and the action for which he was awarded his Military Cross. I have not included all writing about his Company in the battles mentioned below, as they were too numerous. The only way to really understand the full picture of the battles would be to read this very interesting book. Some of the descriptions are very graphic. (This book has recently been republished and is available on the net.)

Pozieres - Page 92

At dusk we reached Sausage Gully, a valley about 400 yards wide and about half a mile long, on the rise at the head of which ran the Contalmaison road. The gully, in addition to being the main avenue for traffic to and from the battle zone at this part of the front, was packed with artillery of every calibre, which kept up a continuous fire on the enemy. It was to this busy spot that the wounded were borne from the front line by stretcher bearers and transferred to horse and motor ambulances. The movement of men and transport gave the gully a scene of indescribable activity and the German artillery fire made it as unhealthy as it was busy. Here we learned that the sixth Brigade was to relieve the Second Brigade, and the 22nd and the 24th Battalions taking over the firing line.

Page 94

It was daylight before “B” Coy. was in position in Kay Trench, where “B’ Coy. of the 22nd Battalion was also posted.

Owing to the nerve-shattered state of the troops going out little information could be gained from them as to the nature of the situation. They had carried out an attack the previous day and had ejected the Hun from the last of his defences in the village. The enemy had retired to a ridge about 350 yards away, and was now occupying a new line of trenches overlooking ours. The only point on which the Second Brigade men had laid much emphasis was the probability of strong counter attacks during the day.

Daylight revealed a scene of desolation. The village of Pozieres was no longer in existence, churned-up earth, heaps of powdered masonry and blasted tree stumps alone marking the site. The only structure which had withstood the bombardment was “Cement House,” also known as “Gibralter,” a former German dugout with a concrete observation post surmounting it, and situated at the entrance of Kay Trench near the Pozieres-Bapaume road. All the surrounding country was in a similar state of upheaval, and was strewn with wreckage, with which was mingled the bodies of many dead.

The enemy did not spare us after daylight revealed our whereabouts. His batteries, which were in great strength on that sector, opened a bombardment on the whole of the Australian positions and maintained a withering fire for 36 hours. Kay Trench, where our “B” Coy. and also “B” Coy. of the 22nd Battalion were crammed in so tightly that men scarcely had room to move, was in a painfully exposed position. The troops suffered heavily, whole sections being killed, buried or wounded.

Page 95

The troops hung on only by spurring themselves with all the gallantry and force of will which British blood could command. In Kay Trench, where the troops had no other duty but the utterly painful one of remaining at their post prepared for action in case they should be needed, the braver men displayed their contempt for death by squatting down and playing cards while earth-shaking explosives fell fast around them; and every time the cards were shuffled the strength of the platoons dwindled away It seemed as if those men, as they played their cards on defiance of fate, were gambling, not for money, but for things which on that field appeared to be indefinitely cheaper – the stakes of life and death. An officer, (Lieut. E.V. Smythe) passing along that trench in the afternoon, sickened by the sight of the dead and wounded, saw the body of a sergeant which had been lifted out of the trench above the spot where the four men were dealing their cards. “You’ve lost your sergeant, I see,” remarked the officer to the group. “Yes,” replied one of the men with a voice which failed in its attempt to conceal the speaker’s emotion: “he was playing cards here with us a few minutes ago when he was hit.”

Another man had taken the sergeant’s hand of cards, and the brave men played on, hardly knowing what cards they dealt, but struggling against their feelings and trying by a display of apparent coolness, to steady the nerves of others around them.

And when the officer came back the four had played their last hand, and had lost. Death had won.

Oh, Pozieres, resting place of heroes.

Retaliation was given by our artillery on the enemy’s front line but this did not seem to affect the persistency of the German gunners.

For most of the time our front line was practically isolated, runners and carrying parties finding it extremely difficult to get through, and it was useless to rely on the telephone, for as fast as our gallant signallers repaired the lines they were broken again by shell fire.

The vicinity of “Gibralter” was a terrible death trap. It lay right on the route of all movement to and from the lines and as the shells crashed in salvoes around the structure men fell right and left. Every track over the remains of the village changed shape a dozen times a day under the deluge of shells that fell there, and men went past “Gibralter” and down “Death” road at the double. Stretcher-bearers with wounded were swallowed up in the inferno, and fatigue parties sometimes had half their numbers cut down getting through.

Gibralter Site October 2007 Part of blockhouse October 2007

Gibralter Site October 2007 Part of blockhouse October 2007

As a matter of fact, when allocating fatigue parties, the staff counted on one-third of the men becoming casualties, so that if two-thirds got through, the required quantities of rations and ammunition would be safely delivered at the firing line.

Every foot of the ground was churned over and over by shell fire, and smoke and fumes blurred the field day and night. It was hell in reality and men who served there proved their valour and faithfulness were beyond measure.

Page 97

Pozieres provided our regimental stretcher–bearers with a task utterly beyond their powers. Each Battalion went into action with 16 bearers (four per company). On that field a hundred bearers per Battalion would have been in keeping with our requirements. On the second day only four of our 16 bearers remained in action, the others having been killed or wounded. In the forward trenches the wounded waited hours for removal. Many of the company men helped with the work of the rescue, and when our transport section heard of the plight of the troops in the line they immediately volunteered for duty as stretcher-bearers. Although some of them were included among the honoured dead before their task was done, the rest never wavered. Every trip to the aid-post left the bearers fewer in numbers, but they carried on their heroic work with coolness and faithfulness, dressing the wounded under hellish fire, and then carrying them away with all possible care. Even when shells fell so close that the debris was thrown over them, they went on calmly, having only one thought, namely the safety of their wounded patients.

The work of regimental stretcher-bearers is not only dangerous, but also the most strenuous duty on a modern battlefield. Some of the bearers at Pozieres, after many hours of unceasing toil, had the muscles of their hands so strained that they could not grip the stretcher handles. Later in the campaign the bearers worked in parties of four and six, and carried the stretchers on their shoulders, but at Pozieres they were fortunate if they could maintain two men per stretcher.

Even the ambulance bearers, who took over the wounded after the regimental bearers had brought them back from the forward positions, found their task almost more than they could cope with.

Page 98

Orders had been issued on the 27th for an attack to be carried out by the 22nd and the 24th Battalions on the night of the 28th-29th July in conjunction with the Seventh Brigade. The objectives of the Sixth Brigade units were the enemy positions along the Courcelette road to our left and running almost at right angles to the line we then held, while the Seventh Brigade were to capture the trenches to the right of the point where the Courcelette road intersected the enemy lines on the ridge.

The hostile artillery fire did not abate until the afternoon of the 28th, and the 22nd and 24th Battalions were then found to be so badly shaken and so depleted in numbers that it was decided to entrust their part of the attack to the 23rd Battalion. Two companies of the 24th Battalion (“C” and “D”) and three companies of the 22nd Battalion were detailed as reserves.

The attack was timed for midnight, and prior to that hour the 23rd Battalion took over our line, our “A” and “B” Coys. withdrawing to Sausage Gully. Before dawn “D” Coy. was also ordered to retire, and on the night of the 30th “C” Coy. joined the other companies in the gully. Our Lewis gunners remained to support the attack.

Page 99

Our sojourn in Sausage Gully was officially described as a period in which we were to “rest and reinforce.” The term “rest” was a misnomer. We lived in shell-holes and battered trenches under the muzzles of countless guns, which blazed away day and night, while Fritz added to the general confusion with frequent bursts of shellfire. In addition, fatigue parties, carrying material and rations to the units in the line, and stretcher-bearing squads had to be continually supplied, with the result that many casualties were sustained.

While we were in the Gully almost 200 reinforcements arrived and were allocated to companies, but many of them, being sent forward immediately with the fatigue parties, became casualties before the platoon commanders had time to include them on their rolls.

ATTACK ON POZIERES RIDGE Page 99

Orders were issued for another attack on Pozieres Ridge, the objectives being two German lines (officially designated as O.G.1 and O.G.2) running to the right from the Courcelette road. The 22nd and 24th Battalions were allocated the left sector of the attack, the Seventh Brigade co-operating on the right. Elaborate preparations were made for the assault, which was to be delivered at 9.15 p.m. on 4th August. A continuous bombardment had been maintained on the objectives for two days to ensure that on this occasion the wire entanglements would be effectively destroyed and the trenches reduced as far as possible to and indefensible condition.

Mouquet Farm October 2007 - the old farm was

Mouquet Farm October 2007 - the old farm was

on the left side of the road.MOUQUET FARM Page 113

September 1916.

When our battalion was looking forward for relief, orders came for a bombing party of 24 men under Lieut. E. V. Smythe (later Temporary Major, M.C. and Bar) to attack Mouquet Farm immediately.

It was regarded by those in the front lines as a suicidal effort but Lieut. Smythe, with characteristic valour and coolness, merely asked if the men were ready, and then set forth to carry out the order. It was found difficult to secure 24 men fit to undertake the task. The party was selected with a forlorn hope.

As our artillery was engaged shelling other localities a bombardment of the Farm by trench mortars was ordered to precede the attack. Only two mortars were left in action in the line, and the ammunition available was so limited that when it had been exhausted the German stronghold had hardly been affected. Representations were therefore made by the acting C.O. (Major G. M. Nicholas, D.S.O.) to Headquarters that the task was impossible without the assistance of heavy artillery, and the projected assault was cancelled.

The audacity of the proposed adventure earned for Lieut. Smythe the title of “Mouquet Bill.” It was fortunate that the operation was abandoned, for the strength of the German position was later demonstrated when the whole of the Fourth Division had to be employed in this sector.

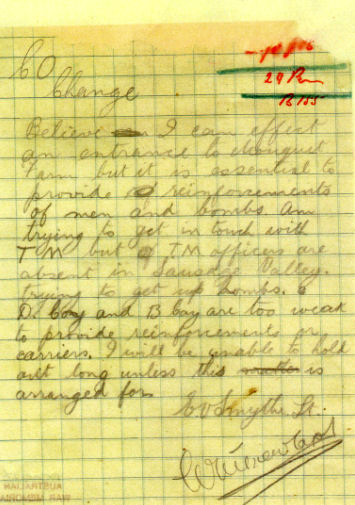

Included with the data is a copy of a report by Capt. E.V. Smythe (a Lieut. at that time).

Reprinted with the permission of the Australian War Memorial Private Records Collection EXDOC026 Album 1

Page 114

The Battalion was relieved on the night of 26th-27th August. It was daylight when the last parties filed through “Tom’s Cut” and the “Avenues” which led to the La Boiselle-Albert road.

Page 115 Gezaincourt

On the 4th (September 1916) the battalion paraded on the high ground above the village, and the acting C.O. Major G.M. Nicholas D.S.O., had some very plain words to say to men whom he described as “shirkers” - men who were inclined to leave the fighting line on the least pretence, and hang around dressing stations seeking the sympathy of the medical officers. These remarks were provoked by the critical position in the line at Mouquet Farm, where a handful of each company held on against tremendous odds, after the battalion was relieved the strength of the unit perceptively increased. The 24th battalion was not unique in that aspect.

Page 140 Warlencourt

February 1917.

The advance through Warlencourt had been accomplished with few casualties.

Page 141

… a brilliant reconnaissance in the direction of Loupart Wood, advancing along the enemy trench for about 1600 yards and gaining valuable information concerning the enemy’s whereabouts.

We were called up again on 2nd March. After taking breath at Sussex Camp, near Bazentin, the Battalion moved forward again by way of Malt Trench and Misty Way to get to grips with Fritz opposite Avesnes les Bapaume, near Grevillers.

Parties led by Capt. J. F. Lloyd and Lieut. E.V. Smythe entered Grevillers, in search of the enemy, but he appeared to have evaded the village.

(Lieut. Smythe was awarded a M.C. for action during this operation.)

Page 142

Lieut. E .V. Smythe temporarily succeeded Captain Lloyd as Commander of “A” Coy. (Captain Lloyd became second-in-command when Major James was wounded.)

Page 144

At dusk on 13 April (1917) the Battalion arrived at Beugnate after a march of about 15 miles, and fixed up shelters fir the night, but orders were received to move on immediately to the front. The troops, exceedingly fatigued, got their equipment together and fell in with misgivings which they did not attempt to disguise. It was at times such as this that the hard life of active service impressed itself most forcibly on the men. The prospects of battle never daunted their spirits when bodily strength felt equal to the task, but to go into action after a day’s march which had reduced them to exhaustion tested man as severely as the fiercest fighting.

“B” Coy. (Capt. Ellwood) and “D” Coy. (Capt. Maxfield) were to move forward with the 22nd Battalion and garrison the line, while “A” Coy. (Capt. Smythe) and “C” Coy. (Capt. Godfrey) were to follow as far as Noreuil.

Page 149 Bullecourt

April - May 1917.

Lieut. E.V. Smythe was promoted to Captain of “A” company by this time. He received a M.I.D. after this action. Our line offered a striking contrast to that of the enemy. The Germans were posted in deep well made trenches and protected dugouts behind a maze of wire. Our line was nothing but a shattered embankment of an old railway line and was approached over the open. Still we reckoned on ousting the Gun and benefiting by his months of labour in having a “house” prepared for our arrival.

Page 155 Bullecourt April - May 1917

On seeing the Fifth Brigade had been held up by the withering fire, Captain Smythe immediately engaged the Germans in the trench on his right flank, and held them in check by establishing a block in the trench 200 yards beyond the sunken road, holding on until about 200 Fifth Brigade men took over the position of the trench. About 30 22nd Battalion men under Captain Kennedy were in the trench on Capt. Smythe’s left flank, and they established a strongpost there, and held the Boche at bay.

(Capt. Smythe was Mentioned in Despatches following this action.)

Page 190 Over The Top Again, Broodseinde Ridge

8 October 1917.

The object of this attack was to carry the line forward to apposition about 200 yards beyond Daisy Wood. The right flank of the 24th Battalion’s Objective was on the Zonnebeke-Moorslede road, with the left flank skirting Daisy Wood.

In view of the reduced strength of the Brigade, it was foreseen that at the conclusion of the attack the numbers of men in action would not be sufficient to dig a continuous trench for the new line, and it was decided to consolidate by establishing a number of mutually supporting strong-posts along the front.

Owing to our small numbers and the loss of two company commanders in the previous attack, it was decided to merge the four companies into three, commanded by Capt. E.V. Smythe M.C., Capt. R.H. Jones and Capt. C.M. Williams.

Page 192

The 24th Battalion went well until our men reached Daisy Wood, where heavy machine-gun and rifle fire were encountered. Casualties had reduced the units until the attackers became divided into small groups operating largely on their own initiative. The company on the right had three of its officers killed, including their commander, Capt. Williams. Captain Smythe was then the only senior officer left. “C” Coy. in the centre, merged with “A” Coy. on the left, and after determined efforts a footing was established. Two platoons of “C” Coy. dug in 40 yards in rear of a hedge and held on in spite of heavy opposition. Capt. Smythe, with the remnants of “A” and “B” Coys. and two platoons of “C” Coy., persisted in the attack on Daisy Wood. At 7.30 a.m. a party from 28th Battalion arrived and filled in the gap between the 23rd and 24th Battalions. The position was painfully obscure during the forenoon. By 2 p.m. Capt. Smythe and his gallant force had cleared Daisy Wood and then held the southern and eastern edges of it, but they were unable, owing to insufficient numbers, to consolidate the whole of the ground over which they had operated.

Page 194.

Capt. Smythe’s gallant leadership, his supervision of the scattered forces during the period of consolidation, and his characteristic tenacity in holding ground that had been won gained him well-earned distinction.

(Capt. Smythe was awarded a Bar to his M.C. following this battle)

The 24th Battalion had gone into action with 12 officers and 220 other ranks, and the casualties were 9 officers and 104 other ranks Of nine officers with the companies, four were killed and four wounded. One company was led out of the line by a lance-corporal.

Page 272 Mt. St. Quentin 28th October 1918

Three patrols, each consisting of one officer and 20 other ranks, were sent forward to establish contact with the enemy. The first patrol, under Lieut. Baldie, moved along Gaudaloupe alley and returned without meeting opposition. The second party let by Lieut. P. E. Smythe (Capt. E.V.Smythe’s brother) moved up Martinique Alley, and in Atilla Trench captured three Germans and a machine-gun. In this exploit Lieut. Smythe personally displayed marked coolness and bravery, and he was awarded the M. C. for his achievement.

Page 276 Mt. St. Quentin 31st August 1918

Our right flank was not yet linked with the 23rd Battalion, and Lieut. P. E. Smythe, with his platoon, spent much anxious time endeavouring to locate that unit

Page 320 –Marcinelle

The C.O. (Lieut. Col. W. E. James, D.S.O.) was called to command at one of the demoblisation camps in England, and Capt. E. V. Smythe M.C., was promoted temporary Major and left (England) with the adjutant (Capt. F.P. Sellick, M.C.) and assistant adjutant (Lieut. R. Rail) to complete the demobilisation of the unit in the field.

The end of excerpts from “Red and White Diamond”

(Captain E. V. Smythe was seconded 1/3/18 to 6th Training Battalion in Fovant, England and was not with the Battalion for Military Actions after that date, as far as I can tell from his documents. I was informed that when he returned to France for the demobilizations, he also conducted the Courts’ Martial of some soldiers that had to be completed before he could return home.)

NEXT >>