Chapter 16

In March the Reverend O'Connell arrived on the Richmond River and performed his duties to his parishioners there. Annie now aged two and Baby Henry aged two months, were christened, with the older children looking on, barefoot but scrubbed clean. Magdalen had long since lost all her hair pins and had not been able to get any more. She repeatedly asked for them to be on the lists which William gave to the captains with whom he dealt, but they all seemed unable to supply them. Perhaps because men would not go into the women's department of the stores, perhaps because they did not consider them important, or perhaps they were in short supply in Sydney. William had made her some wooden clasps to hold her hair tidy but these were not really satisfactory. All their clothes were made of bags or whatever would do, but for the occasion of a visit from their minister they went to as much trouble as they would have anywhere else.

After the ceremony the minister had a meal with them, and he and William talked. He brought news of Woolport and the Settlement, and the friends they had left there. Old Mick Ivory had been in a few court eases over drink. Catherine Irwin, wife of the bird stuffer, had died. Sarah and Joe Cooper had left for Port Macquarie. Mary Bawden had sent a special message of greeting to Magdalen, and the news that she had remarried and was now Mrs Greenwood, with Dr Dobie and Dr Shannon as witnesses.

Mr Greenwood was known as a "gentleman" according to John O'Connell.

"I'm so glad young Tom will have a father and I hope it works out. They were inclined to indulge Tom, being the only surviving child."

"Yes, indeed. 'Spare the rod and spoil the child'. He does give some problems, to be sure. You know Dr Dobie has bought other properties including 'Gordon Brook'. They have begun boiling down there, and Tom the Boatman is kept very busy taking the casks down river. This brings the squatter a minimum price for stock which is otherwise unsaleable. Times have been very bad for some."

The men talked about the recall of Governor Gipps. The minister thought that ordinary men regretted his going, as he really sought to regulate squatting. The usual period for a governor was six years. Gipps' term had expired in February 1844. He felt relieved when the dispatch arrived in August of the following year announcing he could come home.

"He expects to leave later this year, about July," said John O'Connell. "Some people regard him as the worst Governor the Colony has had, but he has genuinely fought for a sound Homestead Law. You know, last year the Colonial Office passed an act giving the squatters the right to lease land at a nominal rent or to buy any portion of it for £1 an acre. Of course they'll buy land along the rivers which makes the adjoining land useless. Governor Gipps believes this regulation will 'Lock up the Land' and that settlers will be plagued by it forever. He was really acting out of idealism and not self-interest as some think."

"Such a shame," said William. "But I'm glad to be able to buy land at last. Not this run though."

They went on to talk about the proposal for a separate Colony from the Clarence River up, which John O'Connell said was the main topic of conversation during his long journey. The squatters were agitating for a new Colony which they proposed to control.

John O'Connell admired William's ship now nearing completion, and commended William's diligence.

After a meal and a rest the minister continued on his way although Magdalen thought he looked as if he needed a good long holiday.

* * *

After three months of struggling with an inadequate milk supply, Magdalen gave up and weaned the baby. Jessie was in calf again, but by now the first calf, Bessie was also milking so there was a plentiful supply for the family. However the baby did not take to cow's milk, and had trouble drinking from a mug. Magdalen tried spooning it into his mouth with little more success. She tried arrowroot when she could get it, and strained porridge and broth.

He was active and agile but thin and fretful, without Eliza's liveliness, Billy's serious alertness, or Annie's prettiness. Magdalen sometimes wondered if she was going to be able to rear this baby, but he grew steadily, sat up, crawled and walked a bit earlier than the others had. He seemed to be a bit desperate trying to make up for his lack of size. Of course there was little time to worry. The day was fully occupied with the struggle to feed and clothe the children and the daily routine which filled her daylight hours.

Their clothes grew daily more ragged. If they wore shoes they were simple home-made rawhide ones. Sugar bags and flour bags made emergency clothes. In no way was their appearance different from the poorest families. But they had a dream, a driving ambition, the determination that one day they would enjoy all the advantages of success. Not that Magdalen thought about it or made plans. She left that to William, and concentrated on getting through one day at a time, every day for her a repeat of the day before and the day before that. But the knowledge was always there that one day her children would have a proper education. Jane, Eliza and Annie would learn accomplishments such as music and art, Billy and Baby Henry would become part of a successful enterprise, and there might even be household help. William would employ men to do the work and he would not need to toil eighteen hours a day.

After the birth of the baby, Magdalen seldom helped William with the ketch. She went only when William could not manage some tricky task. Sometimes he enlisted Jane's aid for an hour or so, occasionally young Fred West was available to help, otherwise he managed by placing the lamp in a strategic position and organising his schedule so that he could concentrate on some small area after dark. The finishing did not require an assistant as frequently as the setting out and early stages of the frame. Occasionally William Clement could help, but he was employed on a two-storey hotel at Gundurimba, and another house for the Wilsons after they sold Lismore House to the Girards, whom William and Magdalen had known from 'Waterview' station at the Settlement.

One afternoon William came home very early. That was nothing unusual. If he had finished hauling there were plenty of other tasks connected with keeping his equipment in order, and he would not come into the hut until mealtime. To-day however he unyoked his team and came straight to the door.

"Have you thought of a name for our first ship?" he asked.

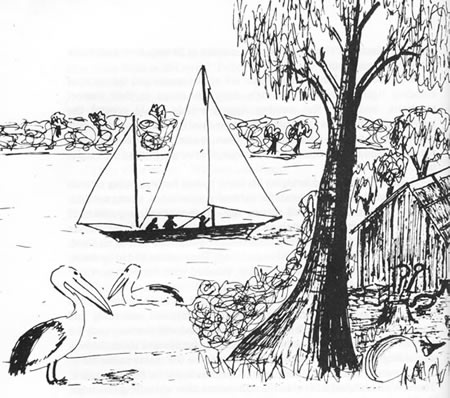

"Name?" asked Magdalen uncomprehending. "Why not call her after those birds on the river? 'Pelican'. They float and glide so gracefully with hardly a movement."

William disappeared for half an hour.

"Well come on down and christen her then."

Magdalen and the children trooped down to the 'ship shed'. Everything was ready, the slip-way was finished and a kangaroo skin full of liquid was hanging by a thong tied to the roof of the hut.

"Only river water," William confessed.

The older children rushed to tell the neighbours. Magdalen swung the skin, splashing water on the hull as William, Mr Clement and young Fred West knocked out the chocks and the little vessel slid noisily down to the river, while the children jumped up and down clapping. There was a splash as the 'Pelican' hit the water and then gradually she stopped bobbing and floated gracefully.

"Papa," said Jane "I wish you had let me do the name."

'Pelican' was painted boldly on the bow. William might be a craftsman but he did not claim to be an artist.

"Next time. I didn't want to wait for you. It would've taken two hours the way you would've done it. It would be dark."

Magdalen's throat ached with pride as she watched the ketch floating on the calm water. She would ride at anchor in sight of their home while William rigged her. He had already arranged for someone to take charge of his team, while he concentrated on his ship. Magdalen knew without being told that he would be sailing her himself to see how she handled. Then she hoped they could begin to relax and enjoy some leisure time together.

Following the launching, the families living at Bullinah celebrated with a spontaneous party around a camp-fire on the beach. Seven-year old Eliza organised all the younger children in a variety of games and contests on the sand, while the everyday food was turned into a feast. Jane at fourteen joined the adults and John Jarrett and Fred West who told anecdotes and talked, until dark, when out came a concertina and the singing began. John Jarrett and Fred West tried to impress everyone with a wrestling match. The adults did not seem much impressed but Jane obviously was. She could not keep her eyes off Fred.

* * *

William began to fit and rig the 'Pelican' and sent word to Sydney that he wanted a sail-maker. Many of the items needed had to be bought, rigging, fathoms of chain, the anchor, canvas in twenty-four inch bolts and other equipment.

Magdalen and Jane watched him set up the masts and the maze of standing rigging which would help keep the masts in their correct positions, and then the running rigging which would control the movement of the spars and sails. It was two-masted with fore and aft sails which would require a smaller crew than square-rigged vessels, a tall mainmast and a small mizzen mast toward the stern in front of the rudder post.

A sail-maker arrived bringing his tools, spikes for separating strands of rope, a sail hook, instruments for tightening up stitches, strong needles. Along the side of each sail a rope was cross-stitched in position to prevent splitting and stretching. The sail-maker pushed his needle through rope and canvas with a hard leather 'palm' tied across his hand. Numerous ropes were attached to each sail. Then spares had to be made, which would be kept in the sail locker, labelled with the mast to which they belonged.

A captain who dealt with William agreed to let him have three experienced crew members while their own ship was unloading and trading on the river. The 'Pelican' had been loaded with timber, ready for such an opportunity. The seamen cursed and complained about the new unyielding canvas. Finally the sails billowed on the masts as the forty-eight ton vessel headed for the bar and the open sea bound for Port Macquarie. There William hired a crew and bought stores after unloading his cargo. He also bought a gossamer for Magdalen to keep away the flies, and acquired a dog named Spot, a small bright-eyed prick-eared mystery breed, a gift for the children which he accepted on impulse from Joe Cooper. Then he was pleased to buy a Nautical Almanac which gave the declination of the sun, moon, stars and planets calculated for every hour of the twenty-four, each day of the year.

On his return he announced he was extremely pleased with his ship and had advertised for a permanent captain and crew for her.

One of the men had injured his hand on the return voyage and Magdalen was called upon to attend to the wound, while the men discussed the future of the vessel and their various plans. William showed no signs of intending to work shorter hours. He talked as if each day had thirty-six hours. She knew that he did not plan to build a permanent home at Bullinah. It had been a suitable place for trading with the captains and hauling timber from the Big Scrub four years ago. Now, new families were arriving every day, the timber was disappearing from the lower river and a number of other teams had come to haul. She knew that William had a plan but until it was properly formulated in his mind and was within reach of becoming a reality, he would say little, only listen and keep his eyes open. He was now telling the men that the best place for a timber dealer would be the Junction, where the North Arm joined the Richmond River, because all the timber from the upper reaches of the river and its tributaries and from the mountainsides, passed that spot. The land behind would be good grazing country, unlike the run at Bullinah. 'Brook' station had been bought by the late James Kenworthy on the advice of Ward Stephens, and was now unoccupied. Nothing definite as said. The men were interested in the hypothetical idea. Magdalen was occupied with bandaging the crushed hand, attending to domestic chores, and watching the early attempts at walking of a restless baby.

Henry, whom they called Harry didn't learn from his mistakes as the other children had. Being burnt once didn't teach him to be careful of the fire when the younger children sat on the log which ran along the front of the fire as a fire-stop, while they ate their meals. While Magdalen attended to the injured man's hand, she had constantly to bring Harry away from the danger. He rushed around regardless of warnings and always had an injury of some sort. Jane continually scolded him and smacked his fingers but he still got into strife.

"Jane dear don't fret so much about him. He'll learn eventually."

"He just doesn't stop to think!" complained Jane.

"You can hardly expect that at his age," said Magdalen wishing she had more time and patience. She wondered if he would be at the most mischievous and unheeding age when her next baby arrived. The next one at least would be born in the Spring, and she would not be so enervated by the humid conditions of Summer.

So while William and the men talked about the new Governor Sir Charles Fitzroy, and the pre-emptive right of the squatters to buy some of their land, and put up permanent homes, and the children fussed over the excited young dog, Magdalen automatically went about her tasks.

* * *

Days went by each one almost identical except in the weather. The chores were the same. There were only a few people with whom they had any real contact. William was away for days at a time as nearby timber had all been felled. Magdalen felt resentful of his freedom to come and go, to meet people, to see what was going on in the world, to discuss public affairs, to make plans and fulfil his ambitions. She found it particularly difficult when he sailed on the 'Pelican' especially in bad weather; then she was anxious as well as depressed.

Magdalen suppressed her feelings of depression as being ungrateful and unwomanly, and would never have dreamed of expressing such sentiments aloud to anyone. It was a woman's place to bear the children and bring them up. No woman could really want to face the hardships and dangers which their men tried to protect them from. Still, fight with it as she might, there was a deep sense of frustration. William had set out with long term plans and his every activity was a step toward achieving his ambition. He had a purpose, something to aim for, and he was progressing. The 'Pelican' and the station at Bullinah were only one step. He had a picture of what he was aiming for, a vision he shared with no-one else. It did not occur to him that it would help Magdalen's spirits to share his thoughts. Women should not have the worries and frustrations of a man's world, and should be protected from unnecessary care and worries about things they could not understand and could do nothing about. Magdalen told herself all these things which she had heard all her life and firmly believed: but that uneasy feeling remained.

William tried to interest her in news of the settlers although as a rule he was one to mind his own business.

"You have heard of Ward Stephens and his neighbour Leycester? They are still arguing about the Disputed Plains and going from one court to another. They will both end up bankrupt if they keep being so stubborn. Most people up-river are exchanging sheep for cattle, including Mr Stephens. A lot more hands are needed on a sheep station especially at shearing. A few stockmen can manage a whole herd of cattle, and take them to market on the hoof."

"And sheep are subject to a lot more diseases aren't they?" Magdalen tried to take an interest.

"Yes. Cattle are more suited to this climate. By the way some of the squatters now have really first-class homes. You should see Lismore House, now that Governor Fitzroy has given them fourteen year leases, and a right to buy part of their land with compensation for improvement. We'll build a grand house quite soon you'll see."

She wondered had she told William about the next baby? Or had he just presumed that there would be another one soon? Harry was walking, running, climbing and always seemed to be underfoot when there was an urgent task to be done. When one baby was at that difficult stage, there was inevitably another baby on the way. The cradle was outgrown by one for a few months before it was occupied by the next. That was the natural way of family life, and there was no real need to make an announcement about another baby. Of course there would be another baby.

Magdalen worried about Harry. He had burnt himself on the hot ashes but still had not learnt to fear the fire. He had pulled things on top of himself, climbing up to reach attractive objects, and as soon as he was alone for a moment, he was climbing again. He had cut a large slice off his thumb with the butcher's knife and seemed to remain unafraid of sharp objects. Magdalen and Jane had to watch him as they had never watched the others. They were forever telling him to stop and be careful and to be good. Jane got quite upset when he seemed to ignore her warnings and remonstrations, and Harry saw no reason to heed a voice that always told him what he wanted not to hear. So he learnt not to hear. He seemed to be able to 'switch off' and often was in a private world of his own. Magdalen worried but what could she do? She asked Eliza to watch Harry, asking Jane to take over some of Eliza's jobs, and that was more successful. Eliza was such an out-going child herself, tolerant and good-tempered, she did not get upset by Harry's curiosity and continual mistakes. She even enjoyed some of his antics and joined him in high spirited games with Spot, a very good-tempered dog with the children. She had a well-developed imagination and an inventive mind. There was not much scope for imagination in the primitive outback life, so Eliza made the most of a good excuse to tell animated stories and make up games for the toddlers. It suited her very well not to be as diligent about work as Jane was, and if she could make work into play she was happy.

* * *

With two sons in the family, the birth of another girl, baby Magdalen was not a disappointment. It was just over ten years since William arrived in the Colony. He was now making steady profits from his ship and from his bullock team and provided Magdalen with many little things which had until then been un-thought of luxuries. He went to Sydney with the intention of going for a pilot's licence for Sydney Harbour and the Richmond and Clarence Rivers, and while in Sydney he took time to order cloth and sewing requirements, a medical box containing Camomile, Friar's Balsam, Epsom salts and Condy's crystals, a pretty shawl for Magdalen and even a Bedourie Oven in which she could make bread. The little luxuries and the new pots and pans, needles, good scissors, strong material for making their clothes, all made life easier, and she felt less tired and depressed since the baby had been born, and Jane had taken over the household to give her mother a couple of weeks in which to regain her strength.

"One day you'll be really glad you've had so much experience at running a home," said Magdalen. "So many girls get married without any idea of cooking or anything unless they're supervised."

Nearly all the girls in the district were married by the age of sixteen, many of them without the aid of a minister who was too far away. Some married themselves by throwing stones into the river and promising to remain married until the stones floated. Others went to great trouble to be married by the minister. Ann King who lived with her family on Ward Stephens' property 'Runnymede', and a hut keeper Tom Hollingworth wanted to be married by Reverend O'Connell. They planned to bring back the minister when Mr King and Tom when to Woolport, now called Grafton, for supplies. When they reached Myrtle Creek they met a traveller from Grafton who told them that the minister was not well enough to undertake the journey. Mr King decided to walk back and bring his daughter, while Tom continued with the team. Mrs King wrapped up Ann's wedding dress and bonnet, and suggested that her twelve-year old brother David should also go with them as company for Ann who was not much older. The young couple were married at Grafton, and came back to 'Runnymede' where Mrs King had the wedding feast prepared. The celebrations went on for a week with many neighbours calling on the newlyweds and joining in the dancing, the only music available being a Jew's harp played by Tom, the young husband who was called 'Tom the Snob' (cobbler's man). It was too far for William and Magdalen to go with their five little ones, but they allowed Jane to go with the Clements. Fred West and John Jarrett and other young people were also there to join in the rare festivities.

There was no shortage of single men in the district, and most of them were keen to have wives. For the girls there was no future other than marriage and most of them thought that the sooner they settled down to have families of their own, the better.

Magdalen expected that she would lose Jane in the near future and it was a comforting thought that the girl was well prepared for household duties. She hoped that Jane would not have to endure the hardships of her parents. But if doing without meant that eventually they would have a proper house with proper beds and furniture, and education for the children, then it was all worthwhile. If only she knew exactly what William intended and how much longer they would live in a slab hut. But she knew he would not commit himself any further so it was no use pressing him. Just trust his judgement.

William had put his ship in charge of a recognised captain, Captain Wilson, who could take her into any port on the coast of Australia and take advantage of any contracts available.

"You know you can tell a good captain by his ability to feel a change in the weather or wind direction. He can steer by the feel of the wind on his cheek, and can 'smell' danger," William was fully confident in his choice. He planned to stay at Bullinah repairing vessels, hauling timber, trading and making plans.

"We'll soon be getting a proper house," he promised when Magdalen asked for the door to be repaired.

"Will we have the money for sawn timber, board floor, shingled roof and glazed windows?" asked Magdalen.

"Should do."

She had to be content with that.

As William made more and more reference to his intention of buying a property and building a house, Jane began to hint that she might not be with them if she got married. Fred West was a frequent visitor, so her parents were not surprised when Fred asked if they might be married.

William and Magdalen had ambivalent feelings about the match, as they felt that they hardly knew Fred even though they had known him for a long time. As a shipwright he had good prospects, and was good-natured and well-liked and not a heavy drinker. Jane was quite infatuated. She met very few people and did not make friends easily, and when Fred showed an interest she was swept off her feet. Although very practical she was not good at personal relationships, and usually was to be found on the periphery of social gatherings. Fred had been most persistent until Jane's parents gave their consent for the marriage to take place before the move from Bullinah.

On 6th December 1849 the new minister for the Clarence District arrived at Bullinah to perform the ceremony. Fred asked John Wright, son of Billy Wright shipwright and cedar-dealer of Rocky Mouth to be his witness and Jane asked her mother, having no girl-friends old enough to be witnesses. The chaplain told them that their friend Reverend John O'Connell had died of consumption over a year ago on board the 'Coquette', having been advised to try a sea voyage for his health. The new minister was the Rev Coles Child, who had recently graduated from Cambridge, and was young and fit, and of a stronger constitution than his predecessor. After the ceremony he joined the people of Bullinah in a wedding feast. Magdalen felt disappointed that their eldest daughter's wedding plans had not given her time to organise anything special. The minister continued his journey, which he would be expected to make twice a year, marrying, baptising, burying. Fred and Jane went to Rocky Mouth where Fred was employed by Billy Wright as a ship-builder on a 150 ton brig, 'The Prince of Wales'. Another Fred West, a distant relation, was also employed there and he had a son called Fred West, which caused some confusion.

"I'm not at all keen on that Billy Wright's dealings," said William. "I hope Fred isn't influenced by him."

"I'm not too sure about some of Fred's stories. I think he's inclined to exaggerate his achievements. I do hope Jane can settle him down."

There was no time for Magdalen to worry how her daughter was managing. William announced that he had succeeded in negotiating for 'Brook' station. The previous owner James Kenworthy had been a successful merchant in Sydney and had bought the station on the Richmond River, opposite its junction with the North Arm, on the advice of Ward Stephens of 'Runnymede'. Ward Stephens and his neighbour were now both ruined because of their continued litigation over the Disputed Plains. Damages of one farthing were awarded to Leycester by the Privy Council in England.

James Kenworthy had died soon after taking Ward Stephens' advice, and as he was insolvent, it took some time for his estate to be settled and the property to be available. It was customary to sell the stock, and the run was thrown in, if the buyer wanted it, the stock being more valuable as the run was only lease-hold. It was just what William wanted. The property was at the most strategic point on the river for the purpose he had in mind. The small amount of stock was a good stand-by, and even when all the timber had disappeared from the whole district, the stock would remain valuable. In the meantime, for ship-building, repairs and cedar-dealing, it was ideal.

William made all the necessary negotiations and arrangements.

"Ready to move?" he asked. "For the last time."

"Packing up again! Where is this 'Brook' station?"

"Only fifty miles up-river. To the Junction. Near the first hut we had when we came to the Richmond."

"That seems a life-time ago. Will I ever forget that journey! Six weeks on a dray in the Wet season!"

"Not this time! Are you disappointed?"

"Indeed no!"

"Tell me about it," begged Eliza who had often heard from Jane, about the dray trip, and felt that she was cheated by having been too small to remember.

"It rained all the way," said Magdalen. "I'll tell you about it later." She was thinking of a long low house with a wide verandah, green creepers, a gracious lawn, flower beds sweeping down to the river bank. She pictured her daughters in flowing gowns enjoying the elegant life. Was this the dream William had had when he sent for her in Plymouth ten years ago?

Her spirits soared. Although she was now thirty-six, she felt for a moment like Cinderella. "Silly," she told herself. "You're more like the ugly step-mother," as she looked at her wrinkled and calloused hands and sunburnt arms, and felt her weather-beaten face. She looked at Eliza, blooming and far more like Cinderella, her lightly-tanned skin glowing with health and natural beauty. Let her rags be transformed into a beautiful gown and take her from the ashes and the dairy, the wash-trough and the pig-sty, and give her leisure to follow lady-like pursuits appropriate to an eight-year old daughter of a land-owner. And Billy, Annie, Harry and Baby Magdalen, let them grow up with all the advantages they could offer.

NEXT >>