Chapter 17

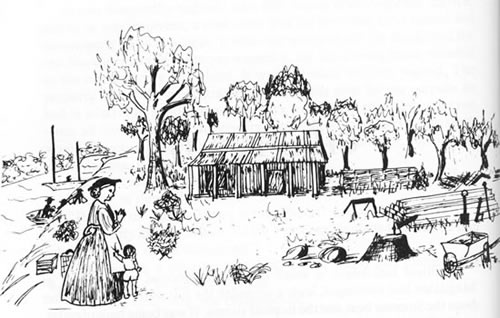

William had begun a small tongue-and-grooved cottage, just as Magdalen had envisaged, with a verandah the full width to give shelter from the Summer heat and the tropical storms. It was being built of cedar, and built to last. If times continued to be prosperous for them, they could extend without major alterations. Although it was far from finished, William decided that they should move to the site and 'camp' in the building so that he could concentrate on its completion. The Wet season was approaching, the house at Bullinah needed urgent repairs to keep it habitable, and travelling between the two houses was very time consuming. So when next the 'Pelican' came through the Heads, he organised their departure up-river on her.

When Magdalen saw the little house, she was enraptured and lost for words. The frame was finished and the wall boards in place but when they went inside, it was apparent that there was much to be done. Internal bracing and lining were lacking. The rooms were bare of furniture. Tools and materials were stacked in the corners.

"We'll need some furniture," said William. "Start a list."

"Proper beds first," was all Magdalen could think of.

"I've already ordered iron beds and bed linen," said William.

It seemed unbelievable to stand at their own front door and look down the bank to the river where the 'Pelican' lay at anchor, knowing that there were cattle in the hinterland which were all theirs, and that if they chose they could soon buy the property and really own that too. The Commissioner could not refuse to renew the lease. It would belong to them and their sons.

The district was all rich scrubland, and very flat behind the levees which flanked the river, with swampy areas. Much of the timber had been cut since they had first arrived on the river not far from this spot. The house was on a site above the flood mark only a few yards from the river bank.

There were many Blacks' camps nearby. The nearest white neighbours were at Wardell thirty miles down the river, Gundurimba on the North Arm, Pelican Tree, Woran and Tatham on the South Arm, all cattle stations with a scattering of timber camps and dealers.

William had already established good relations with the Aborigines at Box Ridge, a couple of miles behind the house, near a swamp where fresh water was available when the river was salty. The Blacks called the district Kurichi, 'The meeting of the waters' which two year old Harry pronounced Koowaki.

"Let's call our home Coraki Cottage," suggested Magdalen, settling the bedding into the rooms, on the floor, proper floor boards, where they would sleep until the bedsteads arrived. Baby Magdalen of course had the cedar cradle, the only item of furniture they had bought from Bullinah. William intended to make everything else except the bedsteads, as wooden beds were said to harbour vermin.

A few days after their arrival, a pulling boat drew up to the bank where William had cut a landing space. The men drew the boat up, and a ship's captain whom William recognised, climbed up the rough steps in the bank and approached the cottage.

"My ship has been wrecked south of the Heads with a good cargo of cedar. Some has been washed onto the beach, and some could be got off the ship if the weather keeps calm. I believe you have the only team on the south side?"

"That is right. You want me to bring the team down? I would have to swim them across Bungawalbyn Creek, cross to Evans Head and along the beach towards the Richmond."

"Could you come immediately in case the weather changes again? I think the Wet may be starting. How long do you reckon it would take you?"

"Hard to say. We'll leave as soon as I can yoke up. Billy, go and see where the bullocks are?"

Billy ran off obediently, and Eliza and Spot went too, not to miss the excitement of the event. Magdalen prepared food for everyone including something for William to take with him. Bush scones, 'Beggars on the coals' were the simplest and quickest refreshment with mugs of tea, and slices of corned beef.

Magdalen told the captain "If a bullock strays he has to be followed on foot and literally walked down from exhaustion. William sometimes has to follow one nearly all day."

On this occasion the bullocks were not too far away. William and the children located and yoked them. Everything was ready for departure. The captain and his men returned to the pulling boat and set out for the Heads, while William and the team set out overland. Magdalen and the five children were alone in the new incomplete house. There was no sense of hardship about that. William was often away. It was the location they were not used to. At the Heads even when they had first arrived there had been the 'new chums' Pearson Simpson and Tommy Service, and quite soon other cedar-cutters and families such as the Wilsons and Clements. For the first time there was nobody except the Blacks.

There had been trouble with the Blacks everywhere. At Kangaroo Creek in the Clarence District, Aborigines had been poisoned by arsenic put into flour and left where they would find it. Many died. The whole district was nauseated.

Even people who treated the natives well were constantly vigilant and took no unnecessary chances. Magdalen put fear from her thoughts. She stood at the back door of their cottage and looked south over the plain studded with cattle, and saw the smoke of the fires among the distant trees. Her mind was full of the impossible dream come true. In real life people like themselves just did not become land-owners. It was almost indecent in the Old Country for people to be ambitious above their station. In the Colony most of the people who had tried to better themselves had gone bankrupt in the Depression if they had taken credit, or had not prospered greatly. Only the picked character could achieve such success. It took judgement and foresight as well as a degree of luck, and a willingness to makeshift and endure hardships for years with patience, until the desired goal could be achieved. Some hard-working men had risen from the lowest levels of society to small commercial enterprises, but very few men without any financial backing, rose from employee to a large land-owner.

* * *

A few days after William left for the Heads, another storm arose. Magdalen hoped that by now William had completed retrieving the timber, and would soon be on his way back. During the night the storm intensified and the unfinished building showed the strain of withstanding the violent tropical winds. Magdalen lay listening to the timber moving, hoping that the incomplete house was safe.

William arrived back the next day to find that the whole house had been blow sideways. The roof was still intact almost on the ground. The tongue-and-grooved timber had separated, not having been braced, and lay scattered everywhere. William raced up to the wreckage, calling out desperately. The living area was exposed to the elements. The bedrooms were covered by the roof. The family was safe under the roof. When he learned that they were unharmed but trapped, he began to remove timber so that they could get out.

"What have you done to the house while I've been away?" he asked as he rubbed his chin contemplating the misfortune.

"Things have been re-arranged a bit."

"Anybody hurt at all?"

"No. We nearly got blown to pieces, that's all. Was your trip successful? Are you hungry?"

"Yes to both questions. It looks as if the timber is not much damaged. I'll be able to rebuild with the same stuff. Only this time I'll get it finished before I go off about other business."

In a very tense situation, they spoke flippantly. The improvised entrance was used to come and go, while William organised some men to help him replace the walls and roof in the conventional positions, before the Wet season began in earnest. He borrowed a small tent in which they would live as best they could in the meantime. When Jane and Fred came to make sure no-one was hurt, they were full of enthusiasm for the married state. Fred had a lot of relatives with whom they spent most of their time at parties.

Another visitor to Coraki was Henry Barnes whose advice William sought in connection with his stock. 'Brook' station included a number of cattle, it was not certain how many. They would just be a side-line, secondary to trading and ship-repairs. Henry examined Coraki Cottage now being rebuilt and firmly braced, then walked with William to look at some of the stock. His comments were acknowledged as being those of an expert. There had been some rain and much of the low-lying land was water-logged, and the ground was very difficult to traverse. The cattle wandered out to the low ridges near the Blacks' camp.

Henry said that he had been recently appointed as postmaster, a capacity in which he had been acting for some time.

"No-one really wants the job," he explained. "The salary isn't good, not worth it to me, because of the pressure of other work, but someone has to."

Until then it had been relayed by squatters or their messengers or anyone known to be trustworthy who happened to be in Woolport on business. Now it came regularly to 'Tomki'. Clark Irving planned to build a hotel 'The Durham Ox', which would serve as post-office as well as place of rest and refreshments for travellers and a meeting-place where squatters might meet socially and transact business. It would be close to 'The Crossing' on the main route north.

"I expect the children miss the quiet beaches at the Heads?" asked Henry. "The river would be much too fast for swimming even in the Dry? At least it won't be salty now. Do you think it will flood near the house?"

"I checked before I started to build. The cottage will always be on dry land even in a flood. There's a lot of low land between here and there, behind the natural levees. Now have a look at these animals. What would you think if they were yours?"

Henry was able to point out to his friend some points which needed watching. On their way back to the house William asked for details of Henry's husbandry.

Henry Barnes had been able to pursue some of his own interests by running some animals of his own under agreement with Clark Irving, his employer; breeding and dealing and building up a reputation as an expert in stock handling. He could never resist the temptation to expand where he saw a chance. He had enough vision to see what capital and wise planning could do.

"I'll never forget how lucky I was to be employed by Clay and Stapleton back in '43, and to be kept on when 'Cassino' was bought by Mr Irving and changed to 'Tomki'. It has been a marvellous opportunity for me."

"And Mr Irving knows he has a man he can trust and a good manager who works non-stop."

"You do a bit of that yourself," laughed Henry. "Work non-stop I mean."

It was true.

Every raft, pulling boat and schooner from the North Arm and the Richmond River up-river of the Junction, passed in front of Coraki Cottage. Many of them found reason to stop. There were many demands on William's time, but the house had first priority, as he replaced the boards, and secured them firmly. Magdalen and the children had never seen sawn boards with grooves for the 'feathers' which held them together, and were most interested in the process. Then the roof was shingled and doors, windows and internal walls fitted. In the living area was a fireplace and oven of brick with a hearth. There was enough room for a large table and chairs to seat the family and visitors, when William should find time to begin the furniture. In the meantime the room was quite bare and they ate their meals sitting on the floor or picnic style on the grass outside.

William decided to order large supplies of goods direct from Sydney so as to be independent of unreliable depots. He built a shed and stocked staples of food, tools and clothing. No longer did Magdalen have to do without essential items because of shipping delays or accidents. Being a very small vessel the 'Pelican' laden with 22,000 feet of cedar, eight casks of tallow, fourteen hides and 3,000 boards, did not have as much trouble crossing the bar as larger ships which were sometimes delayed for weeks.

On every voyage William ordered books for himself and the family. He gave Magdalen a clock to help her with timing her baking, but for some time Magdalen kept it in a cupboard and neglected to wind it, being unsure of telling time and having no confidence in its ability of judging cooking times. Being so used to her intuition, she felt sceptical of mechanics. Jane finally taught Eliza to tell the time and Magdalen came to accept the dependability of the instrument and began to lose her ability to time things without it.

* * *

One Sunday Jane and Fred came to visit. Subconsciously Magdalen noted that Jane was just as slim as ever, thin when compared with her mother. Fred had an abscess on his arm and Jane asked what she could do to draw it.

"A warm poultice and a cooling aperient medicine. Go and get some bread for a poultice, put hot water on it and bind it over the arm. Give him ten or twelve drops of laudanum if the pain gets severe." Jane went to attend to her husband while Magdalen put on the kettle.

"It is ten years since we left England," said Jane on coming back into the kitchen.

"Is it really?" said Magdalen, getting out cups. The only time Magdalen thought about the land of her birth was to marvel at the change in their status. Her days were too busy to give her any time for homesickness and since her mother had died she felt there were no real ties with the Old Country. Ten years this month she calculated. What a lot had happened. Now she had five children to organise, animals and a garden to supervise and William to support in his diverse interests, and another baby due next Spring.

"This baby will be the first white child born in the district," she remarked to Jane.

"Mama, you've had alternately a girl and a boy after Eliza, so this one should be a boy. Can you tell?"

"Some people can by the way the baby lies but I've never been sure. I hope for a boy but we must accept what the stork brings." She had noticed that Eliza was listening.

"Oh Mama!" said the younger girl.

"Eliza don't be too forward about such matters. When you're married is time enough to become curious. Now run along my dear and set the table." Then to Jane she said "Don't talk about it in front of Eliza; she is too young to understand. She'll only be nine when the baby comes."

"Won't she notice you're getting fatter? She knows all about animals."

"She may but don't draw her attention to it. It's not proper. In any case I've been getting a middle-aged spread and even when I'm in the family way it isn't particularly obvious."

"I remember when you were quite small when we were on the ship, you were only half the size."

"I wasn't really well then and never really got my sea legs on the voyage. Since then I've had to be sure to keep my strength up with solid meals, just to keep up with the work and five babies since we arrived. You have to eat for two you know and you never really lose everything you put on. This will be my sixth baby in ten years. You'll know all about it soon enough."

It worried her that Jane had been married for over a year and there was no sign of a family. Perhaps she was not able to have any children. A marriage without children was not blessed with fulfilment. Perhaps Fred would lose interest. It all seemed very haphazard. Those who already had large families continued to have children while others had none. But perhaps it was just as well if Jane did not become a mother yet. Fred did not seem very mature and even Jane who was mature for her years, thought of a baby as a source of entertainment rather than a responsibility.

"Finished your baby talk?" asked Eliza coming back into the room. "There's a broody hen in the shed. Do you want to see her after tea?"

Magdalen had no time to fret about the loss of her youthful figure or the grey hairs which were appearing. She eased herself onto a stool and began to pour the tea.

"How many for tea?"

She would go and supervise the setting of the hen in a box presently. Never a dull moment.

Magdalen and Jane had made a set of clothes for the new baby much more elaborate than any of the others had had. Magdalen could afford soft cool cloth and pretty trimmings, but there was no thought of replacing the cedar cradle which William had made for Eliza. He repolished it and Magdalen put the tiny garments in it, the new merino frock and pelise.

The baby arrived in September, four days before little Magdalen's second birthday. As soon as Magdalen indicated that the time for her confinement was approaching, William sent one of the Blacks who worked for him to fetch his wife, a friendly and dependable woman named Black Mary, who had sometimes helped in the house and garden. The baby was a boy as Jane had predicted, and the shiny black mid-wife was intrigued by the pinkness of him and the blondness of his downy hair and the navy blue of his eyes. He was named Charles after William's youngest brother. In the distance could be heard the sound of singing and bullroarers and native drums, carried over the flat plains from Box Ridge.

Within a few days Black Mary had brought all the friendly gins and lubras and piccaninnies including her own son Mundoon, to marvel at the white child, the first white baby they had seen, to admire the minute white garments and the carved cedar cradle, and to watch the changing of his napkin. From then on there was no shortage of women and girls willing to look after and entertain him. The other children gradually came to accept the presence of Blacks as their regular companions. Some of the men spasmodically worked for William and some of the women for Magdalen. It was appreciated that it was unreasonable to expect Blacks to become full-time employees, but that they often proved better as rafters and bullock-drivers than the timber-cutters were. William supplied food in return for work.

Eliza tied a blue ribbon to the door to indicate that they had a new baby boy. With her mother's guidance, Eliza gave directions to Black Mary and her friends to do the domestic work for two weeks. They dug the garden beds, churned the milk, chopped the kindling, carried water.

In the new house there were also other tasks which were alien to both Eliza and the native women, the new oven to manage, the new linen sheets to beat after each wash day to keep them soft, floors and furniture to be polished, glass windows to be shined. Most of these tasks were neglected until Magdalen was on her feet again. Then she took up her duties and directed the routines. Although they now had several chairs, she preferred to sit on a solid stool to feed the baby as she did not feel safe on a chair, even one made by William.

William was busy building a permanent store and wharf. Each time the 'Pelican' came in there were more goods for the store, to be exchanged for timber. To keep a ship in good running order it had to be dry-docked regularly and its hull cleaned and inspected. If there was any soft planking it would have to be cut away and replaced and caulking renewed. Every rope was renewed regularly and standing rigging replaced ready to take the strain in a sudden storm. William was particular about the care of his ship which continued to bring in a variety of goods until he could supply almost anything the cedar-getters might need in their temporary huts and nomadic lives. As was customary he gave unlimited credit to the men who traded with him, but unlike other dealers he dealt fairly and did not take advantage of their urgent needs. All goods were expensive to transport from Sydney and the dealers could get almost any price they asked for the necessities. Some dealers charged exorbitantly for the service they rendered and the credit they gave, William charged only what was required for him to make a reasonable profit on a transaction, and so the more sober and reasonable cedar-getters preferred to deal with him.

There was always a group of men who gave no thought to the future so long as they could forget their doubts with their mates around a keg. They continued to exchange logs for stores and liquor and didn't bother to question the price while grog was plentiful and the dealer made a show of friendliness.

Three years earlier Billy Wright had brought two shipwrights to his depot further down-river at Rocky Mouth. One of these was called Fred West (F.C. West) which was very confusing to Jane's husband and their colleagues in spite of a considerable difference in age. This situation was solved when the young man left and went to Coraki to work for his father-in-law, at the time working on extensions to Coraki Cottage.

Magdalen and Jane were delighted to be near each other especially as Jane was pregnant at last and was troubled with morning sickness and at eighteen was beginning to feel disillusioned with married life.

"Fred always blames me for everything. He says I'm too intellectual. Too 'full of books' he calls it. I think he already misses the life at Rocky Mouth."

"I expect he's used to the sort of company you get from a lot of relatives. But I'm sure he'll settle down when the baby comes. Is he pleased at the idea of being a father?"

"I suppose so, but he hates me not to be well. If I make the least complaint he gets very irritated."

"It's your duty as a wife not to upset him."

"I know Mama, I know. I just wish he showed some concern."

"Men aren't like that. Women are lucky if their husbands are good to them. Your father for instance is so busy with the property and everything he hardly notices if I'm here so long as the meals are on time."

For William progress was coming slowly but it continued steadily. Everything he did was well done. There were no more temporary huts or ship-sheds made of bark. Every building was planned to be as solid and neat as possible. Young Billy at eight was taught to do his part, with regular tasks to perform with the cattle and bullocks, the store and shipping. He could read quite well and could be useful with checking the unloading of stores when the 'Pelican' came in. He was encouraged to work hard at his lessons. For the girls education was not so important; accomplishments mattered more. For Eliza instruction in drawing and fine needlework came from books.

There was always school in the evenings, with Magdalen teaching the little ones, and now that Jane was nearby she helped her father with lessons for Eliza, Billy and Annie. After two years absence Jane was so much more tolerant and mature in her attitude to the younger children's errors. Her parents were very glad that she had been of an academic nature and had taken her studies so seriously. Jane had missed the atmosphere in which curiosity and learning about the world had been

taken for granted. At Rocky Mouth she had found that she was considered to be too earnest and dreary. Whenever any reading matter came to hand she had not been able to resist the temptation to lose herself for hours at a time. Fred's mates had little time for books, many of them could not read. They were rather carefree at times even irresponsible following the example of Billy Wright. It was good to be in a situation once again where her avid reading habits were not thought of as abnormal.

Sometimes Fred came to Coraki Cottage in the evening but could not be persuaded to join in either as a student or a teacher. He looked through some of William's books and periodicals with half-hearted interest.

Her parents tried to encourage Eliza to follow more lady-like interests than Jane had, but Eliza herself would have preferred to be outdoors more, helping with the animals, if her father had not insisted now that she leave what was considered men's work to the men and boys, and that she should learn womanly tasks.

"When we were at Bullinah you let me, Papa," she said with only a hint of rebellion, which William did not notice because of her winsome ways.

"At Bullinah there was a need. Now there is not. Women were not made to do man's work and unless it is really unavoidable they should not try to walk in the ways of a man."

There was no more discussion but Eliza always managed to avoid the really domestic chores. She could find work in the garden or with the animals which somehow looked like women's work when she did it. Spot was her constant companion. Magdalen thought there had been no such thing as woman's work when she first came to the Colony. She looked at her tough skin and muscular arms. When a job had to be done by a woman on her own, it was done without consideration. Her daughters would never have to make clothes for their children from bags, and shoes from hides. They would never have to cook on smoky outside fires in the rain nor carry buckets of brackish water in searing heat. Like Jane the girls Eliza, Annie and little Magdalen would all marry hardworking, loving husbands who, like her sons would have good prospects and family backing. A few doubts were creeping in about Fred, since he and Jane had come to Coraki. Fred and William had put up a small hut nearby, but Fred had not done anything to improve it, and he seemed to think that William was a hard task-master at his ship-repairing business.

Magdalen's thoughts again went to the Settlement where she and William had had no family support, either moral or financial. She thought of her struggle to learn to cope with pioneering hardships. What William had achieved was all his own and the credit was all due to his foresight and determination, his square dealings and good workmanship.

* * *

Baby Charles was just discovering the pleasure of his feet under him, pulling himself up on the furniture, when Magdalen discovered she was pregnant again. Another Summer baby! She calculated that she would be close to forty, and that Charles would be seventeen months. She wished that the weaning of one baby was not always followed by the coming of another, but she immediately dismissed the thought as unbecoming and ungracious. She had a good loving husband and a wonderful family of well-behaved children, intelligent and industrious. She would soon be approaching the natural end of child-bearing years; until then what could she do? At least she could have as much help in the house as she needed, and with her experience, bringing up children got easier as time went by. But the thought persisted, this was her eighth living child, all were healthy, and that was enough to ensure the inheritance of name and property.

At one year of age Baby Charles became an uncle, when Jane had her daughter, Mary Magdalen. Fred was delighted to be a father, but not so pleased when his sleep was disturbed during the night. Magdalen and William had mixed feelings about being grandparents. They offered the use of the cedar cradle, but to the young parents it looked old-fashioned and well worn, and as William had no time to make another, and Fred showed no inclination to do so, they sent away for a wicker bassinet. Black Mary with Mundoon at her heels, was now a capable house-help, and the little bare hut was soon tidied and the washing and other chores soon done. Within two weeks Jane was again giving lessons to her brothers and sisters, taking her daughter in her basket.

Fred was always welcome, but evidently did not feel at home in Coraki Cottage. More than ever he missed the joviality of life at Rocky Mouth and even the excitement of the occasional lusty brawls.

NEXT >>