Chapter 2

Two weeks later the 'Bessie' was being towed up-river by the crew in the ship's boat and approached the Settlement, half a dozen huts almost hidden among the trees, near a depot on the south bank of the river. Ways for ship-building had been laid in front of the depot and the frame of a vessel was under construction. Two women, a few children and a number of men were on the wharf. William was not there. Magdalen fought to overcome her disappointment.

"I think the whole population is waiting for the 'Bessie'." She was aware of the terrible remoteness in the wilderness of this tiny clearing on the banks of a mighty river, and what the arrival of a ship would mean. Having rowed eighty miles up-river, the crew relaxed for a moment and Captain Freeburn personally helped Magdalen with her luggage. To the men on the wharf he said.

"Do you know of William Yabsley?"

The men gazed at Magdalen. "He's 'ere all right, but not expectin' anyone. He's out in the scrub cutting timber. We wouldn't know 'is whereabouts exactly. They stay out for weeks at a time you know, as long as their flour and tea lasts, livin' off the land."

"How does the timber come to the depot? They must have some sort of transport or communication," asked Magdalen.

"They float the logs down in the floods, and then the men come down and claim them."

Magdalen looked at the bright Spring sky.

"No likelihood of rain," she mused. She spoke flippantly but felt uneasy about what to do next.

"This is Sarah Cooper," the man was saying. "This is Mrs Yabsley. Mrs Cooper's 'usband is Mr Yabsley's mate."

"Mrs Yabsley! Mr Yabsley has been telling us he 'ad sent for you, but he is not expecting you yet. He was planning on goin' to Sydney Town to meet you." She was a large, friendly woman.

Everyone had crowded around with expressions of welcome and helpful suggestions and questions.

"It's quite overwhelming," said Magdalen. "You don't know anything about me." She had expected to be treated as an outcast by the respectable women, at least until they got to know her.

"We know your 'usband, Mrs Yabsley and we know of what he thinks of you," explained Sarah Cooper. "It's an 'ard life here, even for us who are used to it. We can't afford not to be friendly. As soon as I 'eard who you are, I says to myself 'there's a woman with courage.' You'll probably get a shock to see Mr Yabsley. They look like wild men when they come out after weeks in the bush."

"The question is... is there somewhere I can stay? I must learn to look after myself until my husband comes back. Are there any dis-used huts?"

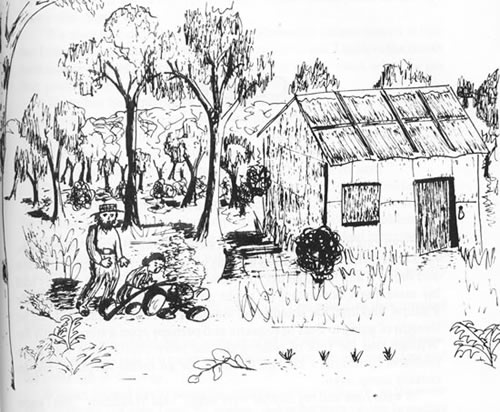

"Well Mr Yabsley did put up a hut next to the shipyard when 'e was workin' for Mr Phillips, and he uses it when he comes back for supplies. It possibly needs repairs, but the men could see to that. Only an outside fire. Do you think you could manage?"

"Will you help me? I have no idea how to start."

"Of course Mrs Yabsley, and you will stay with us for now to see 'ow I do things. Ah Captain Freeburn, will you 'ave Mrs Yabsley's things brought to us. Come along luv."

Magdalen was not easily discouraged, but she had to keep telling herself that if other women could live here, so could she. She would learn. But so much to learn! Her heart sank as she thought how rash she had been to leave Stonequarry before contacting William through Captain Freeburn.

As if Sarah Cooper had read her thoughts, she said "Don't fret. We 'ave all been through it and can 'elp you. You are probably wishin' at this moment that you 'ad never come. People are marvellous. They will never see you in trouble because everyone knows we all need each other. Nobody can afford to be unfriendly. They may need 'elp next. It becomes a way of life. You'll be surprised 'ow quickly you'll learn and soon you'll be 'elping some other new-comer."

Although Sarah said this she was not at all sure that Magdalen would not leave when the ship sailed. The two women walked through the bush to a hut in a tiny clearing, a quarter of a mile back from the river.

"I have no idea of baking bread or washing in a place like this," said Magdalen as if to confirm Sarah's doubts.

"At least you don't 'ave a lot of furniture to polish or silver to clean. Mr Yabsley will have to make a camp oven for bread and I'll show you 'ow to manage it. You'll do most of your cooking on an open fire."

Sarah and Magdalen sat on blocks of wood in Sarah's hut and both women began to prepare the evening meal. Magdalen watched every movement carefully as Sarah took food from the bags hanging from the rafters.

"How do you cope with ants and spiders and snakes?"

"Actually mosquitoes are the biggest pest, especially in summer. Not too bad at this time of year."

"Annie," called Sarah. "Send Joey for water, and you can bring in some firewood." To Magdalen she said "The only good water is in Phillips' waterhole. The river is salty even as far up as this. Eighty miles up!"

She pulled a large iron pot towards her. It swung on a chain above the fire at one end of the hut. In it the meat had been cooking slowly for some time. "What meat do you use?" asked Magdalen.

"This is a wallaby. Young Joey caught one last night in his snares. We eat what we can get... kangaroo, or fish from the river. You can sometimes get salt pork at Price's store since he arrived a few weeks ago. Or dried meat when we can't get fresh. Sheep and cattle are beginning to arrive overland from Tenterfield. A whole cavalcade arrived in June to stock some of the runs up-river. The men exchange timber for beef when they can."

"I hope I can manage to learn something before my husband arrives. I've heard they eat only damper, whatever that is. It sounds monotonous and not very healthy."

"Damper is made of flour and water. No yeast. Mostly washed down with strong black tea. No extras like milk or butter. And lately it 'as been 'ard to get flour. The whole Colony is short of flour because of drought."

"I have brought some vegetable seeds with me, but no wheat. I'll have to plant my corn. And I want a cow and some chickens."

Sarah looked surprised and doubtful. "You may be able to get a heifer from one of the squatters. Most of us don't bother because we'll be movin' on sooner or later. Anyhow I assure you Mr Yabsley 'll be delighted to 'ave a change in 'is diet, no matter 'ow it's cooked. But you'll soon learn. Most of us 'haven't any gardens or animals. Some of the men simply drink all their earnings and never 'ave anything to show for a year's work. Your man isn't like that, neither is mine."

"I'm a bit worried that my husband and I will be almost strangers after three years," said Magdalen when there was a pause in Sarah's flow of speech.

"I dare say it will be 'ard at first, but you needn't worry about Mr Yabsley. He is always talkin' about you and your daughter."

"How I miss Jane! I've left her with my husband's aunt and uncle. It was too uncertain to bring her here."

"That reminds me, I must warn you not to leave the Settlement. The men always carry guns because of the Blacks. We sleep with one a 'and's breadth away at 'ead of the bed. And of course watch out for men. Some are desperate fellows."

"I can't image my husband with a gun."

"No. Some of them shape a piece of wood to look like a gun and blacken it in the ashes. They carry it everywhere. They look like bushrangers."

"Bushrangers?"

"Kind of Highwaymen without any kind of highways."

It was a sobering thought. The women continued to peel vegetables in silence. Sarah put aside the pieces of potato with 'eyes' to plant. Joey and Annie came in with water and wood. Their clothes well-worn and getting too small for them, they were both barefoot.

"This is Mrs Yabsley," said their mother. "Joey is twelve and Annie is ten. They are both growing that fast that I can't keep up with them. Well we're goin' to make room for Mrs Yabsley to stay with us until the men come back. 'ave you any bedding?"

"Yes I brought blankets from home. We had no furniture worth bringing. Everything fitted into my trunk and two baskets."

"You won't need many blankets in this district. Especially in summer. You just need something to protect you from the mosquitoes."

"How long have you been here? Where abouts are you from?"

"We're from north of London. I was brought up on a farm. We've been about a year in the Settlement. We was in Sydney Town for about five years. Early in 1838 a couple of dozen sawyers came to the Big River. Mr Yabsley arrived later that year, not long before us. There were only the timber-getters at Small's depot down river on the island. Then Mr Phillips and Mr Cole opened a store here and Mr Phillips began to build a small ship. Mr Yabsley worked for 'im at times.

"You must get Mr Yabsley to tell you about his arrival here. He worked his way from Sydney Town on a small cutter called 'John', trading here. There were only four 'ands. At the bar the Captain gives orders to get the boat and sound the bar. The bar is very dangerous. Mr Yabsley, the Captain and a sailor got into the boat. A big sea swamped them and the sailor was lost. Mr Yabsley asked the Captain if 'e could swim and 'e says no, but 'e could hold onto a rope on the boat. Mr Yabsley swims and tows the boat to shore. A strong wind blows the cutter out of the sea with the mate and the other sailor and they didn't return for two days. The Captain and Mr Yabsley walked along the beach for two days and nights without no food or flint for fire. The vessel crossed in all right, picked up the Captain and Mr Yabsley, then drifted up the river to the Settlement."

Magdalen felt a tinge of pride and a shiver of horror. She turned away quickly. There were so many dangers in this enormous untamed country. Even now he could be...

* * *

"So here you are."

Magdalen jumped, as she squatted by the smoky fire outside William's little bark hut with its stringy-bark roof, trying to coax damp leaves to burn. Her face was smudged her eyes were smarting and watering from the smoke.

Her hair, usually tidy, hung in wisps around her face. The frustration and loneliness of the past weeks were in her expression. She was not a country girl and had had a lot of problems. At the sound of the unexpected voice she started and nearly overbalanced in her skirt.

"William?" she said without turning around. "Is that you?"

He helped her to her feet and the tears now flowed down her cheeks.

"Is that all you have to say?" She laughed self-consciously, wiping her eyes with her apron. "Oh dear, I did plan to be clean at least when you arrived. Let me look at you." She tried to smooth her hair and brush away her tears with her sooty hand. Through dim eyes she saw him, his familiar gingery hair, rather longer than before, and his most recent hair-cut evidently from a work-mate, a roughly trimmed beard on his firm chin, his clothes now in urgent need of repair. Above all under his cabbage tree hat, the same grey eyes, the eyes that expressed far more than the non-committal words.

"So here you are," she teased. "Yes here I am. By the way you say it, you'd think I had just gone into another room and you had come looking for me, instead of me following you halfway around the world. And what was worse, trying to find you once we got to New South Wales!"

"I didn't expect to get a letter from you first. I've written to Uncle Gilbert to ask him to collect my mail and send it to me. You've arrived first."

"Actually I've brought your mail."

"And Jane?"

"I really didn't know what to do. I left Jane with Uncle William and Aunt Ann. They insisted and I believe it was best. I went to the Market Wharf and asked the captains if they knew you, until I met Captain Freeburn and here I am. I can't get used to the idea that until I left Plymouth, I had never been more than twenty miles from home. This is like the ends of the earth. Why ever here?"

"I could hardly ask permission to leave the ship. It was not likely to be granted. So like a lot of others I just left. If I had stayed near Sydney Town I might have been seen. I heard about the Big River, and took the first ship."

"That explains what your uncle Gilbert meant about not being able to help me find you, because of his position."

"You saw Uncle Gilbert? I expected he was embarrassed by my desertion from the Navy."

"Yes. He directed me to Stonequarry. Uncle William remembered you talking about a man from the 'Beagle' who was working at Parramatta."

"Richard Payne?"

"Yes, and Richard Payne told him that you had met Richard Craig who had discovered the Big River and that you were very interested in his story about the timber."

"Richard Craig now lives in the district. Up-river on one of the runs called the 'Eatonswill'. But he wouldn't know I am here. I didn't know myself whether I would stay or not."

"Well Richard Payne suggested enquiring of the captains of coastal shipping. So I did until I met this captain who thought he remembered your name. The easiest way to find out for certain was to come myself."

"You've had quite a time. Poor Marley."

"I hear you had an experience at the bar yourself. Mrs Cooper told me about it."

"Mm. We got a little wet. But... the question is what should we do now? I've been making good money and have saved every penny I could."

"I think you would like to settle here, aren't I right? I think the challenge of this country gets you."

"Maybe. The space and freedom get into the blood. And the thought of being one's own master, perhaps even owning land one day." He sounded almost passionate for an undemonstrative man. He was not used to probing into his own motives and his inner feelings. But his reasoning suggested that he had energy and the perseverance and the adaptability to cope with life on the fringe of civilisation. The challenge of it did thrill him and offer the possibility of a better future, but he was reluctant to presume that Magdalen would feel it too. Many of the wives could not face the hardship, the loneliness and the dangers, so he had not looked too far ahead. He was not surprised at her willingness to accept the life, nor at her perceptiveness in seeing into his heart.

"Anyhow," he said "we can see how we go in a few weeks. You'll have to learn to do things you never thought of in Plymouth."

"I know. I've already started. But I'm not having much success with this fire," and she made a move towards it.

He held her gently. She turned slowly towards him. He held her small hands in his rough calloused ones.

"Your hands would soon get rough and your skin dark."

She did not answer, but shrugged to say that she did not even consider it.

He touched her cheek with the back of his fingers. Her skin was suntanned but still soft and smooth. In that moment it was as if they had never been apart. Any uncertainties there had been before, no longer existed. The years apart had changed them both but had changed nothing between them.

"William, there is so much to talk about. Most of it will have to wait, but I have to tell you that we lost another baby after you left, another little girl. I called her Magdalen Reid."

"When was that? How did you manage?" He held her close.

"Oh, I managed all right. She is born on the 24th of February seven months after you left and died two weeks later. It was that dreadful unhealthy room in George's Lane with the stench of filth. I'm not sorry to be away, even to a bark hut."

"If we stay, Marley, I'll start some improvements right away. We can send for Jane, settle down and raise a proper family and have a proper house."

That night on the skins and blankets which formed their bed on the dirt floor, their next child was conceived.

NEXT >>