Chapter 31

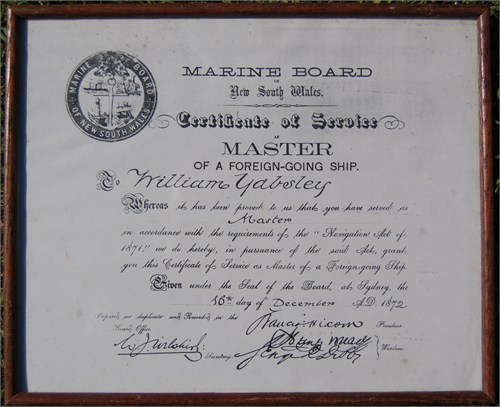

For over twenty years William had been sailing his own ships up and down the coast and into the rivers to see how they handled and at times when he could find no suitable captain. With the increase in population and the amount of shipping, and especially with the greater size and speed of vessels, it became necessary for tighter regulation and for William to apply for his Master's ticket. This he obtained in December. When the certificate arrived, Lizzie asked Oliver to make a frame for it. "You're a proper Captain now," she said giving her father a hug. But William shrugged that it would make no real difference to him.

* * *

When Magdalen had had her first holiday in Sydney seven years ago, it had taken her a while to get used to being away from home. In the meantime she had a few trips in the district and was learning how to enjoy the freedom from responsibility which came when the children were all grown up. She and William and Lizzie had another trip to Sydney, this time on the 'Examiner'. She really enjoyed herself, in spite of the fact that advancing years and increasing weight made her less active, and she managed to do and see many interesting things.

"The port of Sydney must get busier every day," she commented looking at the forest of masts and funnels in the harbour. "More funnels these days."

"If Premier Parkes has his way and expands the railways, that will make a difference to the coastal trade," observed William. "He has approved a railway from Grafton to Glen Innes or Tenterfield with a branch line to Casino and Lismore. That'll make a difference to the Richmond too."

Magdalen had a long shopping list. Lizzie had come with them on her first holiday in the City and was almost overcome with excitement at the variety of materials, dresses, trimmings, household objects and furnishings. With great difficulty Magdalen prevented her from spending a small fortune, but allowed her to buy some pretty things for her trousseau, and as presents for her sisters and the children.

Sydney cove 1870

* * *

The 'Index' a steam tug was launched on 1st May 1874, two years after the 'Examiner' had gone aground. She was fifty tons and seventy feet long and did eight knots on her trials. Bill Yeager still had his little 'Keystone' a puffing little steam drogher, and had also progressed to the acquisition of the barque 'Amphritite', a great achievement for a young man who had arrived penniless on the river fifteen years before, and who had towed vessels with his pulling boat. Recently he had personally cleared the channel of the South Arm to expedite drogher traffic to Casino. He was now a highly respected member of the community and had a young family.

The trend was toward bigger vessels which carried more cargo and handled better in rough weather, but were difficult to manage in the rivers and over the bars. The railway was still only talk, and the river remained the highway, and Coraki was never without some passing traffic and other vessels moored at the wharf.

In June the 'Index' was ready to tow the 'Schoolboy' on trial down the river and to Grafton where she discharged her cargo. They returned to Coraki with the 'Index' still towing the 'Schoolboy'. William was well satisfied making only minor alterations, before he put his tug in charge of Captain Lachlan McKinnon. A bachelor of forty, he had served on twenty-five ships in the Atlantic, Mediterranean and China Seas. He was the eldest son of Donald McKinnon who had settled at 'Oakfield', Coraki, eight years before. The 'Index' was the first vessel of which he was the master.

Tom Fenwick of Ballina, another tug owner, also a Scot, was not as cool and mild as Lachlan McKinnon. He had no intention of sharing the trade with a rival. He had seen the need of a steam tug, and had ordered a vessel of fifty-four tons, the 'Alchemist', which arrived about the same time as the 'Index', a slightly smaller tug.

William said "When I began the 'Index' I intended her to tow my own ships and in between hire her to anyone wanting a tug. I thought of applying for a Government subsidy for operating her at the Heads. No doubt Mr Fenwick had that in mind too when he bought the 'Alchemist'. I'm sure he has no intention of being beaten. I believe Mr Bawden supports the idea of a Government tug for the Richmond River Heads, in Parliament."

"Pity the 'Index' took so long, with all the delays. But isn't there enough work to keep two tugs busy?"

"I would think so, but I've heard tales of Fenwick's temper, and I'm afraid he's pretty stubborn."

So it proved. The two tugs waited at the Heads for the signal from the flag on the north head that indicated that a ship was approaching. One captain signalled to Tom Fenwick that he would take a tow from the 'Alchemist' but changed his mind and took the 'Index' instead. At this Tom Fenwick climbed on board the schooner and thrashed the Skipper on his own quarter-deck. If the nuggety little master of the 'Alchemist' wanted to be aggressive and upset himself when he did not get the first tow, Lachlan McKinnon was not going to let it worry him. There were always more vessels, and taking the second one did not make him feel threatened. The charge to tow a schooner to Lismore and back was £26; 'in, up and out', and each tug could tow two or three ships at a time.

The 'Index', William's 50 ton paddle steamer and the 'Amphitrite' Bill Yeager's 129 ton barque, in the Richmond River at Lismore.

(by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)

The conflict became known as the Battle of the Ballina Bar. So long as the 'Index' made a profit, William was not concerned about the rivalry between the tugs. At the moment he was building a punt thirty feet long for carrying sugar cane, and planning another ship, a large steamer. There was so much activity, so many things to organise.

Thomas Bawden from the Clarence River, who was now forty-four and Charles Fawcett from the Richmond River, now aged sixty, opposed each other for election. There had been a lot of talk about a railway from Woodburn to Iluka, more roads and bridges, but there was no progress. Most of the voters from the northern river voted for Fawcett, and Bawden had lost some favour even on the Clarence. People said he had changed since he had got into Parliament. William voted for Tom Bawden, and he and Magdalen were pleased when the son of their old friend was again successful at the polls. They were not so happy with William's brother John, who was undergoing treatment for a mysterious disease, which was never discussed.

"He was asking for trouble, leading a life of indulgence, and indolence," was all William would say.

James Stocks who had now moved to Lismore where his son, John selected 'Caniaba', lost his wife after a long illness and the Yabsley family attended the funeral, having a great respect for their medical man.

Captain William Kinny and Jane (by courtesy of E Kinny, Kogarah)

This year also brought a second son to Jane and William Kinny. They called him Harry. Magdalen was determined to be with Jane for at least a few weeks. Charley and Tommy were glad to accompany her and call upon Grace and Mary Jane McDougall at the same time. Most of Jane's children did not know their grandmother, except Mary who had recently married James Marx and would make Magdalen and William great-grandparents next year. Mr Marx in his strong German accent explained to Magdalen how he was trying to grow grape vines for wine making. The McDougalls also made Magdalen very welcome and she continued to call on them after Charley and Tommy had returned to work at Coraki. The village of Fernmount was most attractive to Magdalen and she felt satisfied that Jane and William had made a very fortunate choice. She felt sorry when the time came for her to leave.

Mary Marx

* * *

William Clement worked his sugar mill with his horses. His profit for the season was £126. His partner Snow, said they would make twice as much with a steam engine, and they signed an agreement to buy an engine and boiler for £609 to be repaid in six annual instalments. The Alpha Mill and wharf were then in the midst of large cane fields along North Creek. Sugar growers mortgaged their land to buy expensive steam mills, while sugar brought £32 to £36 a ton.

Tom Fenwick was still aggressive to Lachlan McKinnon who generally managed to ignore his displays of antagonism. The 'Schoolboy' and the 'Examiner' made regular trips to Sydney and other ports except for a few days when the engine and boiler were taken out of the 'Examiner'. Keel blocks were laid in the Ship Shed for the new steamer and moulds were made. William senior made a model one hundred and forty feet long, while his son drafted the plans. The vessel was to be called the 'Beagle'. At the same time sugar punts were also being built.

* * *

One Sunday morning in Spring Lizzie aged twenty-three and Oliver Jones of the same age were married at Coraki Cottage.

And Annie married James Stocks. She had long awaited the day when she would be able to marry someone who suited her tastes. James was a striking figure and was admired as an eloquent speaker and good administrator and for his interest in public affairs. His son John was training to become a solicitor. Annie was in her element and felt ecstatically happy as his wife. She played the part well and became a leading lady in the social life of the town, having a good dress sense and always looking smart. James began to build an imposing house at 'Caniaba' and Annie felt that it was worth the wait to marry the right man. James always called her Ann being a more dignified name for a mature woman.

Harry remained the only one not married. Jane's next baby was another daughter, Elizabeth. Young Magdalen and Thomas King brought their baby Charles when they came to Coraki to visit, and her father had to take a needle out of her foot. They also brought the news that Thomas had qualified as a shipwright and was now studying for his Master's certificate for the harbours and rivers. Eliza and John Robinson had eight children while Frances and William had seven. A few days before Christmas, Henry Cook, Frances' father was killed in his own orchard by his horse dragging him after he was swept off by a branch. It was a very sad Christmas.

There were so many diverse activities and so many people with whom they had an involvement, that there always seemed to be something happening. The days and years seemed to go so quickly. "I don't know if it's because I'm older or because we are busier, but every year goes faster than the last. It's quite terrifying. I'm over sixty so I suppose I can't expect to be around too much longer."

"You'll be here for a long time yet. You're too tough to give in to old age," laughed the children.

"Well I hope I go quickly, like poor Mr Cook, but perhaps not quite as sudden. I want to leave things in order."

"Not like that please Mother," said Eliza. "It was such a shock to John and his mother. They were not at all prepared for such an accident. He mightn't have known anything about it but we all did."

"Yes I know my dear," said Magdalen. "I mean I would hate a long illness. And I would hate to be dependent for years. But it's like having babies. We have no choice about when these things happen. It's in the hands of the Maker."

During the following year James and Ann broke the news that they would be parents by the end of the year. Everyone was concerned that Ann was already thirty-three and should have her family as soon as possible. Every year made it more risky for her to have her first child. As the year went on it was suspected that she might be having twins. Magdalen was worried about her having her first confinement at her age, let alone twins. The babies arrived on the last day of 1876 a boy and a girl, James and Maude. After the birth Ann had a lot of trouble with haemorrhaging and could not feed the babies for more than a few weeks. She had the best of care and attention, but seemed to lack her previous vitality. Maude seemed healthy but little James had problems with bronchitis.

* * *

William sent Lachlan McKinnon to Sydney with the 'Index' to have her modified and when she returned a faster tug William leased a wharf in Ballina.

The previous July, Lachlan McKinnon had brought his new wife to live at Ballina and all the ships in the harbour had 'showed bunting' in their honour and Tom Fenwick was most put out. Lachlan joined the Ballina Improvement Society and his accounts of experiences overseas were well received, while Tom Fenwick seemed to find nothing but trouble. He had recently run a brigantine onto South Spit and wrecked her and nearly lost his own drogher. Some of the ships' masters declined to take a tow from him after that. He lost two of his own ships from unexplained accidents. One day in October he had missed the only ship to cross the bar that day and, overcome with rage, ran his tug into the 'Index' trying to put her out of action.

A few days later, as no work was likely for some time Tom Fenwick had let his engineer, fireman and deckhand go ashore for a break. At dawn he went on to his verandah and saw the north head flagstaff signalling that a tug was wanted. He rushed out, stoking his furnace and preparing to cast off, rushing about frantically performing the duties of skipper and the crew. He was so determined to beat the 'Index' and had actually got across the bar and within hailing distance of the schooner before he realised that he was still in his night-shirt.

How Magdalen laughed when she heard about the incident.

"He hurts himself more than he hurts anyone else," she said. "This will make him worse than ever."

By November he was so full of resentment that he accosted Captain McKinnon and threatened to cripple him and wreck the 'Index'. The police were notified and William came down to discuss the matter.

"There is enough work for both of you, and you will gain nothing by being aggressive. Make a set of rules as to who will take which ships and let each have a fair share."

Tom Fenwick agreed to abide by the regulations which the two tug masters drew up, but he seemed quite incapable of controlling his feelings. He chased the 'Index', stopped in front of her, nearly causing a collision. His new tug arrived three times the size of the 'Index' and he anchored his two tugs, one each side of the 'Index'. When a job loomed up, one of his tugs would move across his rival's bows and stay there while his other vessel raced out to take the tow.

* * *

The new steamer the 'Beagle' was nearly completed. It was 229 tons and a very fine ship. Building Government punts and repairing damaged ships kept William more than busy. Magdalen wondered when he was going to stop working so hard. At sixty-five she was really slowing down, while William seemed to be trying to keep up the pace of his younger days. He even talked about a trip home to England to look at the latest screw steamers and their construction. Magdalen had no desire to go at all.

One newspaper at the time reported "His works at Coraki are not surpassed in the Colony." William's reputation as a man of indomitable strength and courage had travelled far. It was said that difficulties and disasters only stimulated him to greater effort.

The 'Beagle' was launched according to their traditions just before Christmas and was fitted with her screw shaft, funnel, rudder and propeller. A pair of sheerlegs was erected to take in the boiler and the engine. William was very pleased with her. In April they got up steam in the boiler for the first time and took the grandchildren on a trial trip to Lismore. On the way home the children stayed in the engine room to keep warm and Alice now aged eight got overheated and very red in the face. The next day she was ill with a sore face and after a few days during which the inflammation spread, her father went to Lismore for the doctor. Frances stayed by her bedside and sponged her continually. Magdalen called frequently to help. By the time the doctor arrived vesicles had appeared and burst and the infection had spread to her eyelids which were so swollen that Alice could not open her eyes.

"Erysipelas - a feverish disease, mostly of the face. You said she got hot in the engine-room of a ship? Probably from that." He left medicine and instructions.

Her father stayed with her all day, Magdalen and Frances kept the other children away as much as possible as Alice was crying all day with the pain. The next day William wrote:-

6/5/77 Death entered our house at half past eleven at night and took dear Alice who died after great suffering from Erysipelas of the face.

7/5/77 Buried poor dear Alice at Coraki's burying ground.

Magdalen felt relief that the child was no longer in pain but felt guilty at the thought. She remembered the babies she had lost in Plymouth and the grief she had felt which was not as bad as that for a child or grandchild you have known and loved for eight years. Where was the justice?

The 'Beagle' was sold for £5000. Magdalen was glad it was sold because of the constant reminder of Alice and her terrible ordeal. William was more than happy with the price he got from the New Zealand buyer. Later in the year he went to Ballina and withdrew the 'Index' from the tug-boat war and disbanded the crew. Captain McKinnon returned to 'Oakfield' Coraki to plant sugar cane with his brothers.

The 'Index' was taken back to the shipyard, the engine and boiler removed and the tug lifted out of the water for major repairs to the keel and deck. The 'Quicksilver', after twenty-two years of good service, was condemned for scrap.

Thomas Bawden still pressed for a Government subsidised tug, without success. William still hoped to get the job. At last a bridge was actually being built across the river at Casino. In the next election, the local man Charles Fawcett was elected with a large majority. He was now aged sixty-nine and had a long white beard which inspired the name of 'Daddy Fawcett'. He continued to press for conserving the timber.

William Clement found that the boiler he had bought for the Alpha Sugar Mill was not adequate. Machinery costing £327 was not made according to his partner's specifications and did not arrive in time for the '77 season. Clement bought machinery and borrowed £355 from William Yabsley at 6% interest. Clement's partner resigned from the Alpha Sugar Works and refused to work at the mill but William still had faith that his old friend was a good business man and could succeed at this as he had with other enterprises, given time and enough capital. Clement received a letter from a storekeeper at Casino telling him that his sugar was better than any from the Clarence River.

Captain Lachlan McKinnon planted sugar cane while waiting for another opportunity. William intended to give him the position of master when there was a vacancy. He was soon able to invite him to become captain of the 'Examiner' the most popular ship on the river.

"Now you really can look down on Tom Fenwick as he tows you across the bar," said Magdalen. "He was so ambitious he wouldn't give you a fair chance and now you're far superior and haven't hurt anyone."

William now aged sixty-six planned a trip to England to learn some of the latest trends in steamers, and to visit his remaining relatives in the Old Country. He would be away for about six months altogether. When he had left England forty years before, the journey took six months each way. Before setting out he made a will to ensure that his family was taken care of in case of accident. As Annie had married a wealthy man she was to receive only £100. The proceeds of the sale of the 'Schoolboy' were to be shared by Magdalen and their four other daughters. The boys already had their properties by selection, some of them were now freehold. They were to get William's stock on condition that they were to keep the number of cattle and horses and not reduce them by sale or slaughter to below the present number, and pay their mother £3 a week for her maintenance as long as she lived.

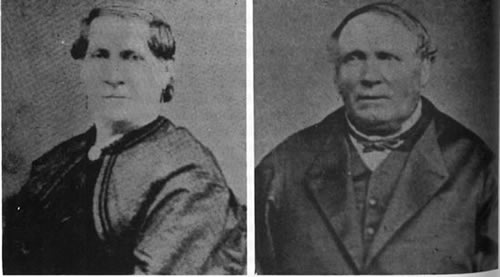

The family also insisted that William and Magdalen have their portraits painted before William left.

"Who would want paintings of a couple of old folks like us?" Magdalen wanted to know, but the children would not listen to any objections. When they were finished she put them away in a back room because they reminded her too pointedly of the rapidly passing years.

On 9th April William left Coraki for Grafton where he picked up the steamer for Sydney to sail in the Government steamer for England via the Suez Canal which was still considered a great novelty.

* * *

William and Magdalen Yabsley. (by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)

A month later, James Stocks sent word to Magdalen that Baby James and Ann were ill. Ann had never been well after the birth of her twins, who were now seventeen months old. She seemed to succumb to bronchial disorders especially in winter if the weather was wet. The doctor said she had congestion of the lungs and he had done all he could do. On 11th May she died at 'Caniaba'. Magdalen was heartbroken, not so much because of her own loss, but on behalf of the little twins and their father who had lost two wives, and now had the motherless babies to care for. Baby James was seriously ill and caused grave concern. Magdalen tried to replace the mother he so plainly fretted for but with all her experience and patience could not pacify him.

James' son by his first marriage was planning to get married soon, and his fiancée was able to spend a lot of time at 'Caniaba' with the babies. Marion Breckenridge and John Stocks had been courting for some time, and Marion's face was quite familiar to the twins. She had often been there to help when Ann was not well. However she got no response from Baby James. He cried and cried, weakly, day after day.

Four days later he also died.

First Alice. Now Annie and James. Life was so fragile and uncertain. You worked so hard to bring up children and they were taken so suddenly. Magdalen did not question the Divine Plan, but she did not pretend to understand why. There was also a terrifying fear for William's safety and an enormous loneliness without his presence. She had hated the idea of his going away as she felt she might lose him on the voyage. Every evening she crossed a day off the calendar and counted the days to his return. In this crisis with Annie and Baby James she wished more than ever that he were here to give support. He seemed so strong and indestructible and his presence was always reassuring but Magdalen' s nightmares about him drowning persisted. Would he ever come back? Days dragged.

On 27th May, John Yabsley died at Ballina and William junior was called upon to make arrangements for his burial at the Ballina Burial Ground. He had made little contact with the family for some time and nobody really knew much about his illness. William was most reluctant to elaborate.

"We'll remember him for the Annual Regatta he organised," he said. "Let's leave it at that."

Magdalen was too full of grief for her daughter and grandchildren to have very much for her brother-in-law who was regarded as rather dissolute. Weeks later her sorrow for Ann whom she always referred to as Annie, still choked her as she helped care for Maude. Her premonitions about William drowning still haunted her.

In October William came home on the 'Platypus' and Magdalen breathed in relief at his safe return. What would she have done if she had lost him? She had to keep touching him and holding him in conversation to reassure herself he was really back. He could not understand why she worried so much.

"I'm a tough old bird. You won't be getting rid of me too easily," he said.

Soon afterwards William got a buyer for the 'Examiner' which gave him the capital to plan his next ship. The engine had been removed and she moved only under sail. Fast steamers were demanded now by traders who wanted to get their goods to market speedily.

"We must progress with the times. We can't stand still," he said.

"Just the same," said Magdalen. "I would rather have sail. It's cleaner and less noisy and not as dangerous as these boilers and things. And I hate the coal bunker by the river and the dirty water at the wharf I think we're losing as much as we're gaining."

"Time is so important in business. Look how quickly I got to England and back."

"I know," said Magdalen. "Although it didn't seem quick to me, waiting. But I'm not convinced. The telegraph now that's another thing. I think it will be marvellous when they finish it to Coraki. Then you can contact me when you go to Sydney, to let me know you've arrived safely."

William also thought the telegraph a wonderful invention but had not thought of using it for such a frivolous purpose.

* * *

It was January of the following year. Harry played in a cricket match in Grafton in which he made thirty runs for Coraki and won a gold medal for the highest score. Grafton won by five runs. Magdalen felt so proud of Harry when he came home with the news.

"What a day for playing out in this terrible heat," observed Magdalen. The weather had been excessively hot, and was still searing when the team got home.

"You really look exhausted Harry. William can you spare him for the day?"

"Leave the old 'uns to do all the work while the young 'uns gad about playing cricket," grumbled William who was very busy after his absence in England.

Harry rested for a few hours, then went on with his work but the next day had to stay in bed. Finally a doctor was called, and he announced that Harry was suffering from sunstroke. He was now unconscious. His brother wrote:-

February 19th Henry Yabsley lying abed out of mind.

Thursday 20 Henry my brother will never recover.

Friday 21 Brother Henry is very low with fever.

Saturday 22 Dear brother Harry died on 22nd after suffering for about three weeks from sunstroke. His mind gave way at last and after great agony died quietly at Coraki House at one o'clock in the morning, aged 32 years.

Death was a thing people lived with, every moment. So many died of unknown illnesses and horrible accidents, often with no doctor available. It was inevitable that a family should lose some of its members prematurely and people had come to terms with that prospect especially in the Outback. Magdalen had always felt she would be fortunate if she managed to raise Harry. She had gone through agonies time and time again. But this did not lessen the shock and the disbelief. To lose her two middle children within a few months of each other was something she could not have prepared herself for. Who would be next? The fragility of life haunted her.

On this occasion the family was together to give each other support in expressing their grief. Magdalen confessed that she had nightmares about William drowning. He said he was a good swimmer but had to admit that he had not been in the water for many years and was now nearly sixty-eight, not twenty-eight.

* * *

In March Lismore was declared a Municipality and James Stocks of 'Caniaba' was the first Mayor. Lismore was now a town of five hundred people and still had few roads and no bridge.

"How Annie would have enjoyed being the Mayor's wife," thought Magdalen. "She would have suited the task." James planned to move to Daley St, Lismore and become a chemist and stock-and-station agent. His baby daughter Maude did well in the care of his son John and his fiancée Marion Breckenridge. John was now a solicitor in Ballina.

Coraki was smaller but of greater importance because of its strategic position and was a very busy place with ships coming in for repairs, punts being built, trading in timber, the cattle and other station activities. A bank had opened in the front room of Frances and William's cottage in Coraki, while they were living on another property, until a proper bank was built in the village. The school was flourishing. A Catholic church had been built and more recently a Church of England. The coming of the telegraph was a big event.

Tommy had cleared a cricket pitch on his property and was considered to be one of the best all-rounders on the river.

A new racecourse had been cleared in the flat, south of Spring Hill and races were now held there.

A big racing event was organised for New Year's Day attended by 2000 people from the district. But the main occasion of the year was still the Annual Regatta held on the Queen's birthday.

William made use of the telegraph when Captain Mountain of the 'Schoolboy' died suddenly coming up the river and Captain Pratt wired to know if he could buy half the ship. William answered that he would sell all of her for £2000. The next day the reply came that Captain Pratt would take any offer and William wired that it was granted.

"I expect he'll be here to take charge at the first opportunity. The telegraph makes transactions so much quicker and easier," said William.

"I'm really sad at losing the 'Schoolboy'," said Magdalen. "It's been such a wonderful ship and has given us no trouble and brought us prosperity." She looked at the painting of the ship, now hanging in their house.

"Can't afford to be sentimental," said William trying to repress his own feelings about losing the ship, now moored at his wharf, her masts visible from the verandah.

He wrote to his friend William Clement at Ballina, telling him of the death of Captain Mountain and the sale of the ship and advising him to plant sugar on his land. His friend was now in financial difficulties because of his enterprise with the sugar mill.

Later William again wrote to his friend.

I duly received your statement and what your sons think of it and I have considered about it myself. The darkest hour of the night is just before the morning. For you to sell at the present would be to sacrifice and I think you ought to try your own cane next year. Say nothing about crushing for other people. I was down to see John Thomson this week and he is full of hope. Coming up I met Morrison of Dunbarooba Creek. He was over-hauling a pump and put his finger in to clear it with the engine going and it took the top of his finger off or hurt it very much that he went to Lismore to see a doctor, but to make a short story he is sorry he ever went at the sugar. I am very short of cash at present but let me know when those bills come due. I want a settlement from Cox for some timber or else I must go to the bank to relieve you. What quality of cane have you for next year's crushing, and what claims have your sons to the estate? If you act with caution next crushing if there is any density, you ought to do middling. Write a few lines by return of post. I was on board of the 'Sarah Hixson' when the roof blew off. It was very severe. Yours truly. ( Sgd) W. Yabsley

Soon afterwards Henry Barnes came to Coraki to visit. William and Magdalen had not seen him for a long time, as he was fully occupied with his property and his young family. His older children were nearly grown up, but over the last twenty years there had been a steady increase in the family until he had five sons and five daughters.

Inevitably they reminisced about the Old Days, but the men refused to admit to Magdalen that they regretted some of the changes as being unnecessary and not really good.

"When we arrived here, the hills were completely covered with forest. It's hard to imagine that now. All the timber for miles has been cut and the timber-getters have to go right up to the McPherson Ranges."

"I believe the Government is talking about a need to preserve timber and plant new forest, or eventually it will all be gone."

"A lot of good timber has been wasted. It seems a shame. A lot was burnt for clearing, or washed out to sea, and some left to rot after the best parts were cut out," said Magdalen.

"That's the price of progress. The land had to be cleared for grazing or farming or cane growing or dairying. It's useless otherwise," said Henry.

"Another thing I'm not sure about are these steamers. I hate the noisy dirty things."

"They are so much more dependable than sailing vessels."

"Maybe, but I miss the 'Schoolboy'. She was so beautiful. These engines are against nature."

"That's the idea. Nature is so unreliable," said Henry.

William took no part in the discussion. The philosophy did not interest him. It never occurred to him to doubt that progress was always good. His outlook had been to add something continually to his world. It made him feel there was a purpose to life, a feeling of direction for his energy.

He said "So long as I can see some progress, add a little every day, I feel I'm going somewhere."

Magdalen said "You'll never arrive where you're going. You can't stop your urge to keep improving things. You can't leave anything alone. You should retire and enjoy some leisure."

"That would be no pleasure."

Henry said, "I expect that so long as he's in good health he'll never be able to repress his urge to take an active part in the affairs of the property and the community. That's why he became a J.P. you know."

It was true there was no pleasure for him except in striving, overcoming, achieving. Apart from his trips to Sydney on business, he was up every morning as usual to ring the bell for the family and all the workers to get up. The day was planned and orderly, there were no hassles or overlooked details to cause frustration. Calm as ever, he was always in control. As sharp as ever, no shoddiness passed his keen eye. What big enterprise would he attempt next?

On 17th January 1880 he went to Casino to attend court, by Bill Yeager's steamer the 'Vesta'. As there were some matters to attend to he stayed for four nights and returned by the same steamer.

The steamer was heavily laden with a deck cargo of maize, and William thought it was not correctly stowed. Marine Master Robert Brouse argued that he had often carried forty bags more on deck, but William's opinions were generally greatly valued so the captain agreed to move some of the bags below deck if William took the wheel for him. William complied.

Captain Brouse was moving the bags when they turned a bend in the river. William felt a great surge of movement from the vessel and its cargo, and realised that she was capsizing.

He shouted "She's gone," and immediately jumped overboard.

William swam a few paces and disappeared.

NEXT >>

Sydney cove 1870

Sydney cove 1870  The 'Index', William's 50 ton paddle steamer and the 'Amphitrite' Bill Yeager's 129 ton barque, in the Richmond River at Lismore.

The 'Index', William's 50 ton paddle steamer and the 'Amphitrite' Bill Yeager's 129 ton barque, in the Richmond River at Lismore.  Captain William Kinny and Jane (by courtesy of E Kinny, Kogarah)

Captain William Kinny and Jane (by courtesy of E Kinny, Kogarah) Mary Marx

Mary Marx  William and Magdalen Yabsley. (by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)

William and Magdalen Yabsley. (by courtesy of Richmond River Historical Society)