Chapter 12 SPOTTY DOTTY 1947-48

Our room was unlined fibro, with one small window, a door, a light and a single power point for the electric cooker. Our water came to the door via a hose to a large pot on a box. We used their laundry for water, had a weekly bath in the iron tub which also resided in the laundry. The copper was lit and the warm water was lifted out in a bucket into the tub. Although the sanitary pan service came twice a week for such a large household this was still not sufficient and my uncle quietly removed excess liquid which no doubt helped his vegetable garden grow. He kept everyone supplied with fresh vegetables, having lived for some years on a Soldier Settler block where such a resource was not squandered as it was in the city.

Most things were done in our room, cooking on a tiny cooker in one corner, homework and eating on the small table with Grace reinstated. The small bookcase stood on the other end of the table, partly obscuring the window. Mum's bed stood along one wall, my stretcher bed was pushed under it during the day. The wardrobe which Dad had built was never quite the same after having been sawn in half four years earlier. The double bed had gone, but the dresser, pedestal, sewing machine and glory box were with us once again. All we owned was stacked around, in boxes if it did not fit into the inadequate cupboards. Relatives supplied what we lacked.

Mum put rolled oats to soak overnight so that they would cook more quickly in the morning. If there was a blackout I had to have bread for breakfast. Mum cut my sandwiches while I ate and got dressed for school. I had to leave early each morning to catch the trolley bus to Kogarah and the train to Central where I changed to the Wynyard train, and finally walked along Bradfield Highway. There were sometimes hold-ups due to power shortages, but the railway did have auxiliary generators. When I got home there were chores to be done, sometimes a bit of shopping at Ramsgate before dinner (usually grilled chops, bought daily from the butcher, boiled vegetables many of which came from Uncle Charlie's garden, with few variations), then homework. School work kept me busy during the day and early evening.

In second year at school we moved around more to different classrooms. One of these, partitioned off from its neighbours and without an outside wall or window was dubbed "The Black Hole of Calcutta". I dropped art, sewing and music as these were not my strongest subjects and those of us who did well enough in academic subjects were expected to continue them. Those who did well in science continued, the others did biology. In German we learnt songs including some from "Hansel and Gretel" and traditional German children's songs. I enjoyed this and was not sorry to have chosen German instead of Latin. The only song they learnt was about Popeye the Sailor man (a cartoon character. PARDON MY LATIN)

"Popopulus nauta sum pum pum, (I'm Popeye the sailor man pum pum)

Popopulus nauta sum, (I'm Popeye the sailor man,)

Quad edo spinatem, pugnabo ad finem, (I eat all my spinach I fight to the finish,)

Popopulus nauta sum. (I'm Popeye the sailor man.)

Auntie Ida had a piano, bought for her when she was at High School (also Fort Street). She could play Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata", "The Witches' Flight", "La Golondrina" and "Rendez-Vous". Auntie Dorrie was willing to continue paying for music lessons for me when we found a teacher. Mary also took up lessons again, both using the same teacher and piano at Auntie Ida's for endless scales, the fashion of the time, causing David and Charlie to complain. I was given an old bicycle on which I rode to my lessons.

Margaret's baby arrived in February, a girl whom they named Carol. Soon afterwards it was my 14th birthday. We had a family get-together, (not a birthday party). Auntie Dorrie was sick and could not come personally but had ordered a Globite school case to replace my old one with a broken catch which I had been using until now. The new one had not arrived, because of post-war shortages, so she sent a big box of chocolates with Betty and Uncle Perce. I was not disappointed. The school case would come eventually. It would be of similar quality to the large Globite case Mum had bought when we left Bankstown.

Mum made contact with the local group of Jehovah's Witnesses and was glad to be near her sister. They could talk about many things including their beliefs. Auntie Ida, who was not a regular churchgoer, held a traditional Protestant faith, would listen patiently but was never convinced by Mum's ideas, especially after the time for the predicted Armageddon had come and gone without incident. I had gone about my daily life without giving it much thought. It was never mentioned again to my knowledge. It seemed that every set of beliefs was held by its adherents without requiring scientific proof, so they could never be disproved and simply demanded unquestioning acceptance.

Mum was also glad to have some independence again and to be in charge of her small household. She often allowed me to do the shopping, having helped me to work out a list. I was not unhappy to have cousins of my own age and their friends. Cousin Charlie was very close to my age and also had adolescent uncertainties. He was travelling by steam train to Glenfield and attending Hurlstone Agricultural College. Mary was still at primary school, The Park, planning to go to Kogarah Domestic Science School next year.

Sometimes at the weekend and in holidays we combined sugar, golden syrup and butter and made toffee or by adding carb soda and stirring vigorously, made honeycomb. This could be shared with nearby children when we played "football" in a vacant block opposite. More often there was cricket in the dead-end street nearby. Occasionally as we got bigger and stronger someone's window was broken and had to be paid for, which was only a mild deterrent. Bradman, aged 40 was still the universal hero.

"Here's Bradman," we said of the person taking up the bat. A good bowler was Ray Lindwall - something I did not aspire to and was not encouraged to try.

One of the greatest Australian racehorses of the time was Bernborough. He won almost every event in which he was an entrant. We asked each other "Who do you think you are, Bernborough?" when someone ran fast.

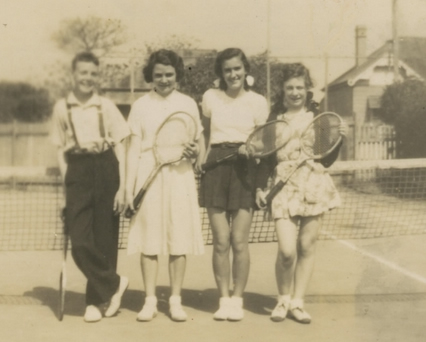

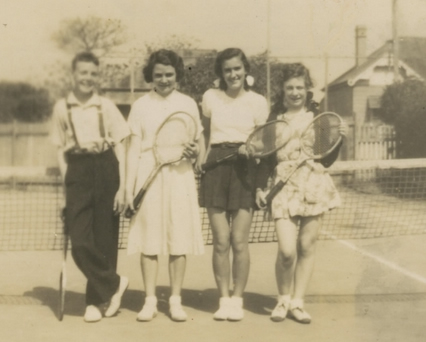

Bill, Dorothy, Jean and Mary

Occasionally we hired a tennis court and shared our tennis rackets for a morning or afternoon. The courts were loam and had to be rolled smooth and marked with white lines. My brother had a bicycle and could come over to visit us, now that we lived in the same area, about eight miles away, and he was old enough to negotiate the suburban traffic alone and so could join some of our games and activities. And there was always Ramsgate Baths which had grown to be the social hub for young people from a large area. We could swim, laugh at ourselves and each other in the distorting mirrors, dive (never well), dive for pennies which the owner threw in a shallow pool and which were then spent in his kiosk, and look at the monkeys in his little zoo. One day a girl was bitten by a monkey and taken to St George hospital. Soon after that the zoo was closed.

Bill was following a technical course at school, as guided by Dad, and doing well in all subjects. He learnt electrical work helping Dad but was given little choice in his daily life, not allowed to waste time on "useless" activities or hobbies, not given any help with school work or a place to study. He was usually compliant. I was definitely more independent and was allowed to be more creative. I thought I was happier than he was, in fact I never thought of myself as particularly unhappy, although I had enjoyed writing melancholy poems. I had a lot of friends at school, was usually optimistic and enjoyed a variety of hobbies and activities. I knew my future would be brighter than the past. My mother was not as critical as Dad, usually saw the bright side of things and was encouraging in her own way.

But all my friends from school lived in a different area and rarely remembered to include me in their outings, parties or picnics and staying overnight with each other. I felt I was missing out, because of still living out of the school district. I worried about what my classmates thought of me and why they overlooked me.

My younger cousins went to the pictures nearly every Friday night with other local young people. I was rarely allowed to go. There was always a serial which frightened Mary who hid behind the seat in front when it got too exciting or terrifying. The films were in black and white, usually two in the evening with a newsreel and a cartoon and mostly not memorable.

My cousin Margaret had a lot of books which I could borrow. These were not illustrated, not being aimed at little children. For relaxation I read all the "Billabong" books by Mary Grant Bruce, other Australian books such as "Dusty" and "Man Shy" by FD Davidson, "Anne of Green Gables" by LM Montgomery, set in Canada, "Girl of the Limberlost" written by Gene Stratton Porter, a naturalist of Indiana, "Lassie Come Home" by Eric Knight, a very popular story about a dog's long journey home from Scotland to Yorkshire during the depression, also made into a film.

My cousin David, eight years older than I was, always called me "Kid". When I objected, he said I should be careful or he'd call me "Spotty Dotty Skinny Kinny". I couldn't think of a suitable retort, so I was stuck with Kid. Mum fostered my interest in writing and encouraged me to continue sending things to the Argonauts. There was a Brains' Trust question on the Argonauts Club "What would you do if your name was Dorothea and everyone called you Dotty?" My answer, describing my predicament earned me a Blue Certificate.

I also wrote a fantasy story I called "The Old Brown House" about a mother surviving in the bush with six children. At Mum's suggestions I wrote the story of my life up until that time. She suggested reversing my initials as in David Copperfield by Charles Dickens. I wanted an unusual Christian name beginning with K. Mum looked in the big dictionary and found Kezia, one of Job's younger children, a Hebrew name. She suggested Dubois so I became Kezia Dubois. This was supposed to be an account of the first fourteen years of my life. The number seven and multiples of seven had some biblical significance.

In describing the little dog belonging to our landlady at Cammeray I wrote "He was a mongrel, foul-smelling and weird-looking and nasty-tempered. He was in his second childhood, old and decrepit, whining and crawling about people's feet and snarling at a word of command". I was definitely not tolerant nor completely accurate. My account was very romantic and greatly influenced by sentimental stories and my imagination. The beginning of an autobiography. A story by Kezia Ruth Dubois

Travelling in the train took over an hour morning and afternoon and this gave me an opportunity to read or to escape to my fantasy-world and I was carried past my station more than once. Sometimes I was so absorbed that I failed to notice when people spoke to me. I thought about a future home and family but never about a husband as I could never imagine what he might do or say. At night I still anticipated coming events, or dwelt upon things that had gone wrong, keeping myself awake for hours.

At school on wet days we were encouraged to spend our lunch time in the hall where records were played on the gramophone and we learnt the Barn Dance, Pride of Erin, Gypsy Tap and Canadian Three Step. These dances came to me very quickly. Waltzing properly was harder, especially as no-one else could do it. I tried on the cement path outside our room at home. Mum was not certain if it was a good thing for a girl my age. I was really rapt in learning to dance and was eager for rainy days.

"You will learn easily when the time is right. I loved dancing when I was a young woman." I found this statement irritating, aimed at deterring me. It did not succeed.

I went into our room and started to do my homework.

"Set the table now," Mum said, expecting me to comply as usual without any obvious unwillingness.

My reply astounded even me, as I heard myself saying "When I'm finished this," suddenly beginning to turn pages at random for a few minutes. I don't know if she was surprised or disturbed or angry. I went on with my homework, my face burning with embarrassment. There was an uncomfortable silence as I packed up. After that to avoid being disobeyed, Mum refrained from giving direct instructions or even requests.

After a while she asked "What frock will you wear to the Bible meeting?" This was her attempt to break the ice. There was virtually no choice, one that Auntie Dorrie had bought for me was the only one I liked, the only one not home-made, by myself.

"I've got too much homework," I replied flatly.

Such a thing had never happened before. At Cammeray I had acquiesced in attending meetings and going from door to door with the "message" but with growing doubts. At Artarmon I did not go, now Mum wanted to start going again. It gave her a sense of belonging. To be told I had to "have faith" did not reduce my scepticism as it implied I should believe in things that cannot be proved and that go against scientific observation. Mum invited one of the boys about my age, who attended the meetings, to come for lunch and cooked macaroni cheese which was possible to do in the little cooker. No doubt she hoped we would establish a friendship, but this did not happen as we had little in common and I would not be pressed. To Mum it was unthinkable not to believe. It would have left an enormous gap in her life. My lack of religion did not leave me empty, but on the contrary I was free to explore and find fulfilment in the natural laws of nature.

Evolution based on physics, geology, anthropology and the study of fossils had seemed to me to be more logical than Adam and Eve and creation of the universe in six "days", each of a thousand years, especially the notion that the whole of mankind was punished for their curiosity in Eden. This I could never tell my mother, having no wish to undermine her faith, but my doubts must have been obvious. Based on early scientific study and observation Copernicus and Galileo saw the universe as different from the beliefs of the time that the earth was the centre of everything. They had a different view of accepted astronomy and for this iniquity people could be burnt at the stake. Even Mercator, the great map maker had in the course of his work come up against religious teachings showing Jerusalem as the centre of the world, which he found unsubstantiated by his evidence. He was also in a dilemma, but tried to find a compromise, knowing he could have lost his head. It was not so bad for me.

My conclusion was that the many sets of beliefs were basically the same and similar to those of more primitive cultures. When things happened that could not be explained, people invented a plausible if supernatural reason. My churchgoing relatives said that most Christian churches agreed that probably the stories of the Old Testament should not be taken literally, but were used to explain puzzling events, which did not mean necessarily they were right. The later development of scientific experimentation led to different answers. An early artist of First Fleet believed there were three kinds of creatures, birds that flew in the air, beasts that crawled on the land and fish that swam in the sea which meant that whales and dolphins had to be called fish! My interest in science fostered curiosity in how things worked and this led to questioning, especially wanting a logical explanation for the many pieces of evidence - fossils and bones of prehistoric creatures including man. I learnt that over the centuries many of the early religious teachings had been discarded in favour of observations and experiment-based evidence. I could not believe that sea shell fossils had been put in mountains to confuse scientists.

My rebellion was just a normal expression of a teenager's need for emotional independence. But it was traumatic to our relationship. Mum felt she had failed in her duty to me. We had been separated for weeks and months when she was in hospital. During her periods at home she felt it imperative to re-establish her authority and influence my behaviour, which had to her become full of impiety and materialism, lacking humility and devotion. I was far too unbridled and spontaneous.

She had expected and always obtained unquestioning if reluctant obedience, reprimanding me mildly when I demurred. When this complete acceptance of her authority no longer existed, our relationship was strained. I was a child, a young adolescent, not to be treated as an adult, but had been forced to make decisions for myself, act independently and take responsibility for long periods. I had readily complied with Auntie Dorrie's wishes for a different reason. I had wanted to, as my preferences were considered without emphasis on "God's will", or searching in the bible for acceptability of the behaviour.

There is nothing more immovable than the attitude of a really unhappy fourteen-year old. Some rebel against everything that is represented or associated with parental control. Others submit outwardly while fostering deep stubborn resentment. Others take the line of least resistance and become submissive, even withdrawn.

My relatives encouraged me not to upset or worry Mum. It was confusing and I found it very difficult to assert myself without causing her to worry. It led to sharing little with her, especially problems which she could not do anything about. My schoolwork was more rewarding and my ability to understand it boosted my self-assurance.

Religion and party politics were not things to be openly discussed but I became aware that the ideas of my aunt and uncle were completely different. There was a big strike among the painters and dockers where Uncle Charlie worked. He was not willingly involved, but found himself on strike, out of work for long periods which caused great hardship and some heated opinions. When overtime was offered he accepted it. There were comments in the house about the unions running the Labor Party, also the influence of Catholicism and the growing dependence of welfare recipients. My mother's family was for generations entrenched in Protestantism, inherited from their Northern Ireland forebears. It was believed that Catholics were, from childhood indoctrinated and were never able to question the teaching of their elders. That was not unique to Catholics.

When I got home from school as the weather got cooler Mum made me a thick slice of toast, cooked under the grill of the little cooker while milk for cocoa was heated on the top.

One day she had got out the eiderdown which had been put away for the summer, and said "The eiderdown is too big for a single bed. Half the feathers have disappeared over the years and it's now very thin. I wonder if I could cut it down for a single bed before the weather gets any colder."

"Wouldn't the feathers fly everywhere? Maybe we could wet them first."

"What a good idea. I'll do that tomorrow. This room will be very cold in the winter. You can have another blanket from my bed, once I get it done."

The wet feathers were transferred to a box, the eiderdown cover cut to single size and the feathers replaced. It hung on the line in the sun until it recovered its former cosy lightness and the enterprise was successfully completed.

Mum's health did not improve. If we were going out we went the long way round to avoid steps, often by several buses. If train travel was the only way, she tried walking up the steps backwards, thinking it might be easier on her heart. While at home she constantly tried to go to the meetings of the Jehovah's Witnesses. She went mainly to daytime meetings. Reluctantly I kept her company to night functions.

But she soon had to go to hospital again. There was no treatment for her heart condition, but sulpha drugs when she got pneumonia. It was accepted that the doctors and hospital controlled what happened to her and I was just an ignorant onlooker.

I had to get up earlier to cut my lunch and get my breakfast. Sometimes Auntie Ida cut my lunch while she was making four others for her family and I sometimes ate my evening meal with them. I visited Mum three or four times a week, bringing home her washing and taking clean nightdresses. Homework, school work and piano practice suffered. Not to mention time to sew, write to the Argonauts, relax or have hobbies!

Mum often had the chance of choosing a piece of music to be played on the "Hospital Half-Hour" on the wireless. When she chose "Mountains of Mourne", although she could have chosen almost anything, I thought her taste very immature! But on the spur of the moment I could not pick one either.

I often joined my cousins Charlie and David who both liked tenors and always listened to the wireless program "World Famous Tenors", especially admiring Beniamino Gigli and Jussi Bjoerling, both still living at the time. Auntie Ida whose favourite singer was Marion Anderson singing "Softly Awakes my Heart", approved as she liked music but Uncle Charlie was quite left out. With the invention of transistors, radio reception would improve. The cabinets in which they were built were usually bakelite, a dark coloured plastic resin which could be moulded. More plastics had been developed during the war and gradually some of these came on to the domestic market.

Uncle Charlie loved to have shiny shoes and was willing, even eager to polish everybody's shoes. He did minor repairs with adhesive and encouraged a trip to the bootmaker when needed. As Auntie Ida found the washing too heavy Uncle Charlie always lifted it out of the copper after it had boiled.

A family gathering

He also did the shopping. Nominally Auntie Ida had charge of the "housekeeping" and the rest of his wage was unquestionably his money. He also took me and my cousins and their friends by bus from Ramsgate Beach to Moore Park to the Royal Agricultural Show and made sure we had money to buy at least one show bag each. At the time they were comparatively affordable and good value to children to whom they were treats.

He bought us all Violet Crumble Bars when occasionally they became available at the shop in Ramsgate. MacRobertson who had invented the popular Freddo Frogs, died and his idea was taken over by Cadbury. One of Uncle Charlie's customs was to buy lottery tickets every pay day. Mum felt that such things were wrong, being a form of gambling. She suggested if he saved the money he could spend it on something worthwhile, but he was convinced he would win one day and in the meantime an occasional small win was an excuse to celebrate and an encouragement to continue.

Sometimes Uncle Eric came to visit bringing with him his retarded son Gordon, who was about nineteen and physically fully grown. We still had our portable gramophone and on it played "The Runaway Train" which Gordon thought was hilarious. He was rolling around on the path, nearly hysterical with laughter.

Beverlee

One day on my way home from school on the trolley bus from Kogarah, another girl in the Fort Street uniform spoke to me. I had not noticed her before. We were the only Fortians living on the Illawarra Line.

"I've seen you on the train," she said. "You always seem to be alone, but I can never attract your attention. Once you stayed on and I wondered if you were daydreaming."

Rather confused, I admitted I had once been carried on to Hurstville station.

"Well you'll have me to remind you now. There are only the two of us from Fort Street in this area. I was accepted because my mother was an old Fortian. By the way my name's Beverlee, spelt double e. I'm in fourth year. We live at Sans Souci. I notice you get out at Ramsgate."

"I'm in second year now. My mother went to Fort Street too. We moved here this year."

"Where did you live before?" asked Beverlee.

"At Cammeray, then with my Aunt and Uncle at Artarmon."

"What about your parents?"

"My mother is in hospital."

"In St George Hospital? Do you go to visit her in the evening? I'll come with you. I know Mother will send her some flowers. When will you be going next?"

She was a very outgoing girl, who approved or disapproved of things with enthusiasm. She came to the hospital and persuaded Mum to let me visit her family. She called her parents Mother and Dad which I found unusual, every mother I knew was Mum. At sixteen she wore lipstick which I thought at first was precocious, but soon got to admire. I avoided doing anything which might make me look conspicuous and sought the periphery of any group. Beverlee ignored my reticence and persuaded me to join in various activities, such as watching her play hockey, and refused to be embarrassed or offended at my self-conscious manner.

After that Beverlee often persuaded Mum to let me do things when I wouldn't even ask. She nurtured my interest in sewing and told me I had lovely hair and beautiful eyes. Her mother gave me advice about trimming for a dress I was making, using material given to me. Beverlee approved of me in spite of my gaucheness.

Mary and Carol

Sometimes Mary and I went to the beach, often taking Margaret's little daughter, Carol and another neighbouring child whose mother paid me to mind her for a few hours on Saturdays. The child always wore beautifully hand-done smocked dresses and matching hair ribbons even to go to the beach. This was the beginning of my baby-sitting career. I also did some knitting for her.

Although Mum encouraged me to be my own person within the restrictions of her beliefs and not to worry about conforming to the fashion, I wanted to fit in. Lacking confidence I usually tried to make myself unnoticed. I would not wear or do anything that attracted attention. My uniform should look identical to all the others. When the maths teacher, in a lesson on proportion, gave an example of how people's freckles increased in the summer and mentioned my name along with a couple of others, my face fell, then I blushed. I tried to reduce my size and disappear behind the girl in front. The teacher said she did not mean to pick on me.

When introduced to people I hung my head and when polite conversation was required I edged away and stood aloof. It's a wonder anyone bothered. I spent a lot of time absorbed in books and reveries and drew lots of house-plans, anticipating a dream home of my own to which I could escape.

Since moving to Ramsgate I seldom went to the Municipal Library to borrow books as it added to the length of time to get home and I was usually too tired. Beverlee gave me "Jane Eyre" by Charlotte Bronte, and in return I crocheted her a bedspread from scraps of wool given to me. Beverlee lent me "This Above All" by the same author as "Lassie Come Home". "This Above All" was a romance set in London during WWII, but I was disappointed, perhaps it was too real for me. Although not described explicitly, it was apparent that the heroine became pregnant before marriage to a soldier whose life was at risk. This was an absolute tragedy in my world. The story did stress that people had to be true to their real feelings.

During the year there was a tour of Australia of The Old Vic Company with Laurence Olivier (later Sir) and Vivienne Leigh, including "Richard III ", "The Rivals" and "School for Scandal". The school took us to see at least one performance. I found the money to attend one and one of the teachers paid for my ticket to another. This was an entirely new, unaccustomed experience and perhaps a little too adult for us. Or maybe we were inadequately prepared, although we had regular days when we put on our own plays in the "gym".

When Ballet Rambert toured Australia we were taken to a matinee performance. In particular "Swan Lake" and Debussy's "L'Apres-midi d'un Faune" immediately captivated me.

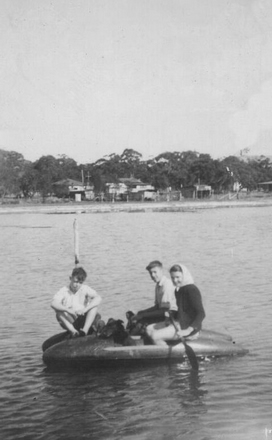

Towards the end of the year Beverlee and I went together to Albion Park Rail to visit Mum's sister, my Auntie Vi, and her family. My Uncle Bill was the shire clerk and lived in a cottage almost at the railway station. The only other house belonged to the station master. My cousins, one my age and one two years younger, had canoes made from tanks from small aeroplanes, and we canoed on Lake Illawarra. One day Beverlee and I set out to climb a nearby mountain, first going to the butcher in Albion Park to buy some steak. It was a lovely experience, getting higher and higher and looking down over the lake, until it began to rain. We couldn't get a fire going and were so hungry we ate our steak half raw before hurrying down. I put my rubber-based sand shoes in the fuel oven to dry, but unfortunately someone stoked up the fire, and a strange and unpleasant smell alerted us to the ruined shoes which dripped out.

Beverlee said that daydreaming was an attempt to escape from reality, not very flattering to friends and family.

"If my life is not to my liking I try to do something to change things."

My natural curiosity about the world began to overcome my "escaping". Mum also talked to me on the subject, suggesting it was selfish to force my friends to make allowances for my self-conscious behaviour, I should think of other people and consider how it made them feel. I tried to think of things to say which would be of interest to make conversation.

I was even able to listen to Beverlee about the problem of men wanting to touch girls. She brought up the subject and I admitted to the problem with men trying to get too close on a crowded train or who "just wanted a cuddle". Most men were just showing normal affection. I could not offend them and didn't know what to do. Beverlee knew. She said she would first tell them plainly to stop and then knee anyone who touched her. Her father had advised her. It was unlikely anyone would intimidate her.

"Then you have to walk away. Let them know you don't want it. No kidding."

I would try to be more assertive but it was very difficult and sometimes simply not possible. I talked to her about the embarrassment of hanging my personal cloths on the line, in full view of everyone walking down the path to the lavatory. There seemed no solution to that. Girls our age mostly had the problem. Beverlee was quite certain that we needed a slide bolt on our door to make sure of our privacy, especially when Mum was in hospital. She organised for her father to put one on.

Dorothy

The next year Charlie and I were in third year and preparing to do the Intermediate Certificate. I could then officially leave or go on to do the Leaving Certificate which was expected of Fort Street girls. We had one period a week for "hobbies" which were debating or drama. I chose the latter but at first did not participate in anything.

Joy and Heather

This was the Centenary of Education. It was celebrated in the Sydney Cricket Ground. Fort Street girls formed the "i" in a tableau of Education and had to wear white dresses reaching a given distance above the knee when kneeling (not too short). We performed some folk dances with crowds of other children, all of which had to be co-ordinated, so that we were all in step.

If I wanted to go out I had to persuade my mother it was a "suitable" event. Usually the classics qualified. Beverlee suggested I should have a real discussion with my mother about my independence, although in practice I had been acting independently in many situations from an early age. I had no idea how to approach the subject with Mum. Everything Beverlee suggested I rejected as beyond me. Mum would have thought teaching children independence meant teaching them to feed and dress themselves and tie shoelaces at an early age, and find their way around in accordance with her directions as they got older. What if the child came up to something unexpected? Did they panic if there was nobody to tell them what to do? Probably about eighteen was the age at which she considered it appropriate to show real initiative and demonstrate independence, by which time the young person could have developed a docile, hesitant attitude. I was not so compliant but did not know how to be assertive without upsetting my mother which I tried to avoid.

Beverlee wanted to go to town to see a Technicolor musical film, "Fantasia".

"It's a very good film, Mrs Kinny. It's some of the greatest classical music like the "Nutcracker Suite" with animation by Walt Disney".

Mum agreed. For the occasion I wore a blue winter suit which I had made with the help of Auntie Nell, who lived round the corner. I had a pattern but needed help with the lining, the bound buttonholes and the fitting especially the sleeves. Auntie Nell, widow of Mum's youngest brother was a good dressmaker and probably would have preferred to take over completely and make a thorough job of it. I also wore a blue cardigan I had made with a knitted bow at the neck and gloves to match. Making my own clothes, I did not have to restrict myself to what was in the shops, or what other people wore. I bought material and copied styles I liked adding my own variations. They were cheaper,original and always attracted admiration. This gave me confidence and stimulated initiative.

I told Beverlee, half proud, half embarrassed "This is my first suit, my first bra and the first time I've been allowed to wear lipstick and shoes with a heel."

The lipstick, borrowed from Mum, was barely enough to be noticed. My heels were just high enough to show that the shoes were not of the "school shoe" type. I was keen to acquire pancake make-up which I believed would cover my freckles but that would have to wait.

We loved the film. A lot of the music I recognised as coming from "Nutcracker Suite" and other familiar compositions. The ballets were wonderful and the animation so well co-ordinated with the sound with sometimes a touch of humour.

Beverlee and I shared so many interests, so many hopes, there was never enough time to tell each other. At last I had a "best friend". A lot of things which I had barely thought about before, suddenly became my raging passion, because Beverlee enjoyed them. I felt possessive of my friend and resented having to share her, although she was two years older and had a wide circle of friends. Music we both loved. She was keen on sport, and I became so. Sport on Monday afternoon made it easier to get over "Mondayitis". It was a tragedy if it rained and Thursday afternoon's lessons were imposed on us.

Bill and I saw each other from time to time. Dad once took us on a camping trip to the Jenolan Caves which I enjoyed immensely and earned two Certificates from the Argonauts for my account which included photos I had taken and developed myself. We heard something of the age of the formations and that the area had once, amazingly, been coral reefs under water. I learnt about stalagmites (growing from the ground) and stalactites (hanging from the ceiling), columns, shawls and straws.

Dorothy, Rita and Bill

Aged about thirteen, Bill once had to put a power point on the wall for people to finish off electrical work begun by Dad. He told us Dad had left live wires in the wall frame, well covered, allowing normal use of electricity, but the people were so angry they refused to pay. Dad thought they may have used this as an excuse. Dad took Bill to Piliga Scrub near Coonabarabran camping for a few weeks. They ate so many quinces and fish Bill was sickened of both, especially quinces. Dad began to build a caravan at Peakhurst in which he planned to live while travelling around as soon as Bill was off his hands.

Bill would soon overtake me in height. For young boys short pants were acceptable, but for young men long pants would be the norm, so he was saving up to acquire a suit.

Sometimes he came to visit Mum in hospital, but at the bedside he was even more reserved than I. Once, when Mum was critically ill and not expected to live through the night, both Dad and Bill came to see her. It was distressing to watch her lying exhausted, her skin, an unhealthy colour, loose on her bones, although she was only in her forties, an oxygen tube taped to her face and an intravenous drip taped to her arm. Was that really a human being... my mother... under all that medical apparatus? I was pretty confused about life and death, suffering and the unfairness of everything.

Jehovah's Witnesses did not believe in blood transfusions and if it was suggested she would have refused as "the life is in the blood". I was beginning to understand that life was in every cell, not just in blood cells. The Red Cross had taken over the collection and storage of blood donations after the war.

It was a topic that could never be brought up, but I thought the belief belonged with "flat earth" ideas.

NEXT >>

Bill, Dorothy, Jean and Mary

Bill, Dorothy, Jean and Mary

A family gathering

A family gathering Beverlee

Beverlee Mary and Carol

Mary and Carol

Dorothy

Dorothy Joy and Heather

Joy and Heather Dorothy, Rita and Bill

Dorothy, Rita and Bill