Chapter 5 MACKS

During the Depression years, some of my mother's family were existing on Soldier Settler blocks in western NSW which were too small for them to make a comfortable living, even when the economic situation improved. Auntie Ida and Uncle Charlie with two children, lived on a block next to Alex and Grace Mackintosh with four children and the two families became good friends. The Mackintoshes finally gave up their farm and bought another out of Windsor. After moving to Sydney Auntie Ida took Mary and young Charlie there a few times for a holiday. Then the Mackintoshes invited us. We had met Mrs Mackintosh once at a Jehovah's Witness convention at Moore Park, Sydney. I remembered calling her Mrs Mack.

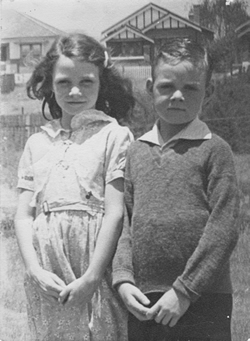

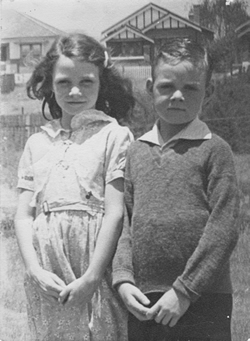

In 1941 Mum, Billy, my cousin Charlie and I went together. It was a big adventure by steam train from Sydney, timed to coincide with their fortnightly shopping expedition to Richmond station where the Macks met us. I was dismayed that I was the only girl, but Mrs Mack assured me there really were two at home.

On the other side of the station at Richmond was a little train known as Pansy, with two carriages which aroused my curiosity. Some people changed trains to go up to Kurrajong in the Blue Mountains and I felt an urge to go with them. One day I would go on that fantastic train across the road, through the park, over the Hawkesbury River, up into the hills and I would see the world.

Everything was new to me and exciting, especially the size of the grocery orders and the size of Woodhills stores at Richmond and Windsor where the Macks shopped. It seemed that no matter what was wanted to replace a broken part of a utensil or tool, it would be found somewhere on a dusty shelf. There was a gas producer on Mack's large car, which took longer to start than a petrol engine. While going from Richmond to Windsor, we had to pass Richmond RAAF Base and during the war it was forbidden to stop. Anyone who did would be suspected of spying. We could see the aeroplanes. Was that suspicious? It was late afternoon by the time they had finished collecting their orders for the farm and the household and the lists of items required by the children at home, one drawing-pad, one reel of cotton, a dozen marbles, a set of coloured pencils, a packet of hairpins, material for simple clothes, a few items of clothing which they had selected from catalogues. As they then had nine children it took a long time and I grew impatient.

Finally they packed everything and everyone into the car, with no thought that it was overloaded. Ice-blocks for the children whose turn it was to stay at home, were transported in a billy-can, arriving in an almost completely liquid state, but still not to be replaced by any other treat. After about an hour chugging along the rough country road, the car passed a cutting known as Crocodile Jaws and began the descent to the Colo River, and then the slow climb to Colo Heights. It took another half hour to the farm. By the time we arrived I had begun to thaw out, chat and ask questions. It felt like a journey to the back of beyond.

Mr Mack, a tall silent grey-haired man, pulled into the drive and was besieged by the rest of the barefoot tribe. The ceremony of the melted ice-blocks took place almost before the engine stopped. Then followed the claiming of orders. Produce for the farm went into the shed. And of course the carrying-in of the major grocery items with which a family of nine children plus visitors were fed. I was glad to meet the only girls in the family, Gracey, a little older and Dawn a little younger than I was. And a beautiful Collie dog they called Lassie like the dog in a popular story of the time "Lassie Come Home".

Beyond the house to the west was a small orchard, the pan toilet, an area of vegetables and charcoal pits known as the ploughing. Wood was burnt slowly in the pits to produce saleable charcoal which I knew because my father also had a gas producer to save petrol. And beyond that ranges of mountains into the sunset.

I took my little case, containing two spare dresses, some underwear, socks and a cardigan to the room Mum and I would share with Gracey and Dawn. As it was hot weather we would sleep under mosquito nets.

By now I was eager to help. We girls put away butter and meat into a drip safe, used to keep food cool and away from ants and flies as we were well beyond power and ice delivery. The safe was a sort of cupboard with hessian sides and the feet standing in water in a breezeway between the living area and some of the additions to the house. Interesting.

Gracey told me "The water soaks up into the hessian and evaporates slowly. The butter and meat will last for a few days without melting or going off. We don't buy too much."

Butter and butcher's meat were treats. Normally excess milk from the cow was set in pans for the cream to rise and especially in summer fresh cream would be used instead of butter and fresh meat would be killed.

The central room of the house had originally been the whole house. Its walls were timber slabs nailed to rough-cut timber frames with a large open fireplace, whitewashed in summer when not in use. A lantern hanging from the rafters cast shadows of the family seated on benches around the scrubbed wooden table. Dinner had been prepared the night before in a big pot and had been put on the fuel stove in the kitchen by the girls. Mrs Mack carried it in and we ate noisily and heartily without having to say Grace. Mum offered to do any mending or simple sewing and helped as she could, we visiting children were a bit awed. Mum and Mrs Mack were soon chatting and sharing experiences.

On both sides of the house and in front, rooms had been added at various times as the need arose, in whatever building material happened to be available, stringy bark or corrugated iron, and whatever style and size seemed appropriate to the materials. The result was architecturally unique. The parents' bedroom was close to the main house and connected by a covered way. The other rooms were used by the boys as they felt inclined, except for the older ones who claimed and modified a room.

Mum stressed to us that they only had tank water and could not afford to waste a drop. No playing with water. The nine children had to share the bath water on bath night. Dirty feet were washed in a tin dish and the water thrown on the garden. We saw no problem in that. There was no question of washing our clothes until wash day, so we wore them, no matter how dirty, which simply didn't matter to us or anyone else. Only Colin, the youngest was excused from this rule and was bathed more often. And then of course the water went to the garden or orchard.

"If it's warm enough," said Mrs Mack "You can have a swim in the shale pit and that will save lighting the chip heater for a day or two."

The road had been greatly improved by workers from the USA, who built a good alternate link between Sydney, Windsor and Singleton and the north in case of invasion. The army had dug a pit for shale to use on the road and the hole was filling with water when it rained. In warm weather a dip in it would save baths. That was a great novel thought - a bath in a large body of water and I forced myself to tolerate the discomfort of getting into the cold water. There was a "raft" made of 44 gallon drums, which was great fun and greatly extended our swimming activities. And a home-made diving board.

Mrs Mack cooked breakfast on the big fuel stove. She made a large quantity of porridge in a big black iron saucepan, using chips and kindling from the box next to the back door to get it alight, then adding pieces from the wood heap outside, near the water tank. There was plenty of fresh milk and a bowl of cream to add to our porridge. Cream was a luxury to me and I was rather greedy until I sickened myself of it. For Mr Mack and the older boys (young men) there were eggs and some bacon and fried bread and and for all plenty of toast made in front of the fire using a toasting fork.

During the morning I explored the house and garden more thoroughly. Every detail was strange and important to me. We played there often with the younger children, or explored the surrounding area.

They had fruit trees, plenty of eggs, rabbits, and even an occasional snake for the pot or yabbies or mussels caught or collected by the children. From time to time they killed an animal, a lamb, or an aged rooster or hen. All the children were used to the idea that they were involved in providing food for the family.

Varieties of cicadas, greengrocers, yellow Mondays, double drummers, black princes, and floury millers as we called them were very familiar. The deafening chorus was part of an Australian summer.

And they knew trees and birds. On one of the walks nearby we saw a hive of native bees. Were there native bees, a whole hive in the Ark? Another time we came to a small cave and I felt like someone discovering a hiding-place, probably well-known to the Mackintosh children. I imagined Adam and Eve must have lived in a cave, as Mum had told me there were no houses in the the Garden of Eden. I pictured myself living in a cave like this. There was plenty of food just for the gathering. I wondered if they ate meat? Where did they get it? In MY cave there was no washing up. In Mack's house we washed up in a tin dish on the kitchen table and threw the water at the base of the lemon tree. This was usually girls' work and we did not object, especially when the boys had to dig a hole for the contents of the lavatory pans, or clean out the smelly chook yard and milking shed.

A row of Mrs Pott's irons always stood at the back of the stove, waiting to be placed over the heat when required. A few days later on ironing day when she had finished making the porridge, Mrs Mack pulled the cover over the fire and placed the irons face down on it ready for the ironing to be done on the kitchen table. We girls helped with putting the clothes away, Mum helped with the ironing.

At Macks we girls could sometimes join some of the male activities, but except for the little boys, they never joined ours.

Naturally the Mackintosh children were quite used to entertaining themselves and there was no limit to what they could investigate, so long as they used common sense. They were keen to try out the new things which had arrived on shopping day. Someone suggested a concert in honour of the visitors. Billy and I were not used to performing but Charlie sang "The Quarter Master's Store". ("There were eggs, eggs, nearly growing legs, in the store, in the store" and so on for umpteen verses). Charlie enjoyed his visit. There was a stack of board games and we played a few new to us, some we knew such as Chinese checkers, draughts, dominoes and cards. The family seemed glad to have new people to play with and enjoyed showing us things unfamiliar to us.

They were keen on cowboy music and introduced me to "You Are My Sunshine" and "There's a Bridle Hanging on the Wall" played on their gramophone. In later years there was an ancient piano on which they taught me to play "chopsticks" on the black notes and which we rattled off as a duet. The words of popular songs of the day were printed in cheap little books called Boomerang Song Books. Music was a normal part of daily life made by us in any way we could.

So many new things to see and do and I joined in enthusiastically. I felt an affinity to this exciting and interesting place .

All too soon it was time to go home. I was given a pink ribbon as a present which acquired for me an enormous value. Someone had thought me worthy of a present and had found something so pretty! We were invited to come again and I knew I would again and again.

The Three Sisters, Katoomba, from east

On another occasion some time later, Mum, Billy and I met Auntie Ida, Charlie and Mary under the clock at Central Station (the universal meeting place for travellers) and went by steam train to the Blue Mountains, where we stayed in "Homedale", a modestly-priced guest house in Katoomba. I believe a family member helped finance this trip. Cotton-wool cloud filled the valley until about ten o'clock when it lifted. One day we went to Echo Point, (would there really have been an answer if we had been allowed to test the echo?), saw the Three Sisters, the perpendicular walls of the valleys which we learnt had hindered the early explorers. The scenery stirred something in me which would grow steadily during my lifetime.

The "mountain devils" (from the seeds cases of Lambertia formosa which had "horns"), made into little souvenirs with red pipe cleaners for tails and red felt cloaks were sold in a shop near Echo Point. We walked down the nearby Giant Stairway, walked along Federal Pass to the Scenic Railway which had originally been built to bring coal up from the valley and luckily for us, some had been converted for passengers which turned out to be more profitable at sixpence a time. Only Mary showed any reluctance, but was overruled and hid her face on the trip up to the top. It was so exciting and just a bit hair-raising.

There were other walks on the plateau, but the roads went up and down quite steeply for my mother who had to take it slowly. In the evenings we did jigsaw puzzles, played simple board games such as Snakes and Ladders, Chinese Checkers and Ludo, also Dominoes or "I spy with my little eye". Meccano was mainly for boys but I was not going to be denied and made my contribution.

I loved the holiday and the wonderful scenery. This was my first experience of our wonderful heritage. It reinforced an urge which would last a lifetime to discover what lay over the horizon. But it lacked the freedom I felt at Macks, perhaps was a bit "civilised", with streets, shops and mothers to organise.

NEXT >>

The Three Sisters, Katoomba, from east

The Three Sisters, Katoomba, from east